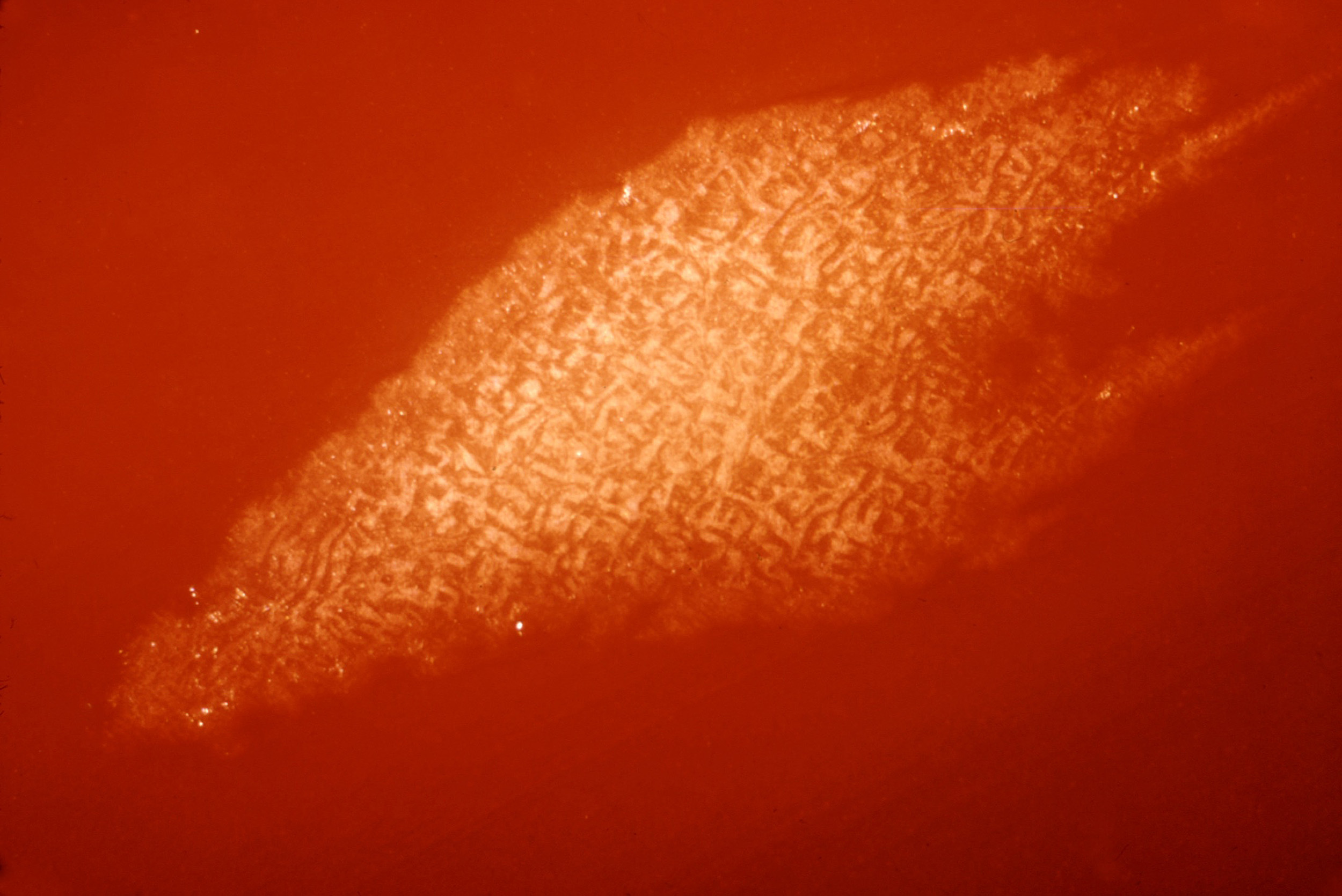

A close-up view of a bacterial colony of botulinum.

Credit: CDC/L.V. Holdeman

A ‘miracle poison’ for novel therapeutics

Researchers make critical advance toward potential new treatments to help neuroregeneration, cytokine storm

When people hear botulinum toxin, they often think of either the cosmetic that makes frown lines disappear or the deadly poison.

But the “miracle poison,” as it’s also known, has long been approved by the F.D.A. to treat a suite of maladies like chronic migraines, uncontrolled blinking, and certain muscle spasms. And now, a team of researchers from Harvard University and the Broad Institute have, for the first time, proved they can rapidly evolve the toxin to target a variety of different proteins, creating a suite of bespoke, super-selective proteases with the potential to aid in neuroregeneration, regulate growth hormones, calm rampant inflammation, or dampen the life-threatening immune response called cytokine storm.

“In theory, there is a really high ceiling for the number and type of conditions where you could intervene,” said Travis Blum, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and first author on the study published in Science. The study was the culmination of a collaboration with Min Dong, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, and David Liu, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and a core faculty member of the Broad.

Together, the team achieved two firsts: They successfully reprogrammed proteases — enzymes that cut proteins to either activate or deactivate them — to cut entirely new protein targets, even some with little or no similarity to the native targets of the starting proteases, and to simultaneously avoid engaging their original targets. They also started to address what Blum called a “classical challenge in biology”: designing treatments that can cross into a cell. Unlike most large proteins, botulinum toxin proteases can enter neurons in large numbers, giving them a wider reach that makes them all the more appealing as potential therapeutics.

Now, the team’s technology can evolve custom proteases with tailor-made instructions for which protein to cut. “Such a capability could make ‘editing the proteome’ feasible,” said Liu, “in ways that complement the recent development of technologies to edit the genome.”

Current gene-editing technologies often target chronic diseases like sickle cell anemia, caused by an underlying genetic error. Correct the error, and the symptoms fade. But some acute illnesses, like neurological damage following a stroke, aren’t caused by a genetic mistake. That’s where protease-based therapies come in: The proteins can help boost the body’s ability to heal something like nerve damage through a temporary or even one-time treatment.

Scientists have been eager to use proteases to treat disease for decades. Unlike antibodies, which can only attack specific alien substances in the body, proteases can find and attach to any number of proteins, and, once bound, can do more than just destroy their target. They could, for example, reactivate dormant proteins.

First author Travis Blum and David Liu.

Photo courtesy of Travis Blum and Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

“Despite these important features, proteases have not been widely adopted as human therapeutics,” said Liu, “primarily because of the lack of a technology to generate proteases that cleave protein targets of our choosing.”

But Liu used a technological invention from his lab: a platform that rapidly evolves novel proteins with valuable features. PACE, Liu said, can evolve dozens of generations of proteins a day with minimal human intervention. Using PACE, the team first taught so-called “promiscuous” proteases — those that naturally target a wide swath of proteins — to stop cutting certain targets and become far more selective. When that worked, they moved on to the bigger challenge: teaching a protease to only recognize an entirely new target, one outside its natural wheelhouse.

“At the outset,” said Blum, “we didn’t know if it was even feasible to take this unique class of proteases and evolve them or teach them to cleave something new because that had never been done before.”

But the proteases outperformed the team’s expectations. With PACE, they evolved four proteases from three families of botulinum toxin; all four had no detected activity on their original targets and cut their new targets with a high level of specificity (ranging from 218- to more than 11 million-fold). The proteases also retained their valuable ability to enter cells. “You end up with a powerful tool to do intracellular therapy,” said Blum. “In theory.”

“In theory” because, while this work provides a strong foundation for the rapid generation of many new proteases with new capabilities, far more work needs to be done before such proteases can be used to treat humans. There are other limitations, too: The proteins are not ideal as treatments for chronic diseases because, over time, the body’s immune system will recognize them as alien substances and attack and defuse them. While botulinum toxin lasts longer than most proteins in cells (up to three months, as opposed to the typical protein life cycle of hours or days), the team’s evolved proteins might end up with shorter lifetimes, which could diminish their effectiveness.

Still, since the immune system takes time to identify foreign substances, the proteases could be effective for temporary treatments. And, to sidestep the immune response, the team is also looking to evolve other classes of mammalian proteases since the human body is less likely to attack proteins that resemble their own. Because their work on botulinum toxin proteases proved so successful, the team plans to continue to tinker with those, too. This means continuing their fruitful collaboration with HMS’s Dong, who not only has the required permission from the Centers for Disease Control to work with botulinum toxin, but also provides critical perspective on the potential medical applications and targets for the proteases.

“We’re still trying to understand the system’s limitations,” said Blum, “but in an ideal world, we can think about using these toxins to theoretically cleave any protein of interest.” They just have to choose which proteins to go after next.