‘We’re so much more than our day job’

1st University-wide Harvard Staff Art Show celebrates employees’ whole selves

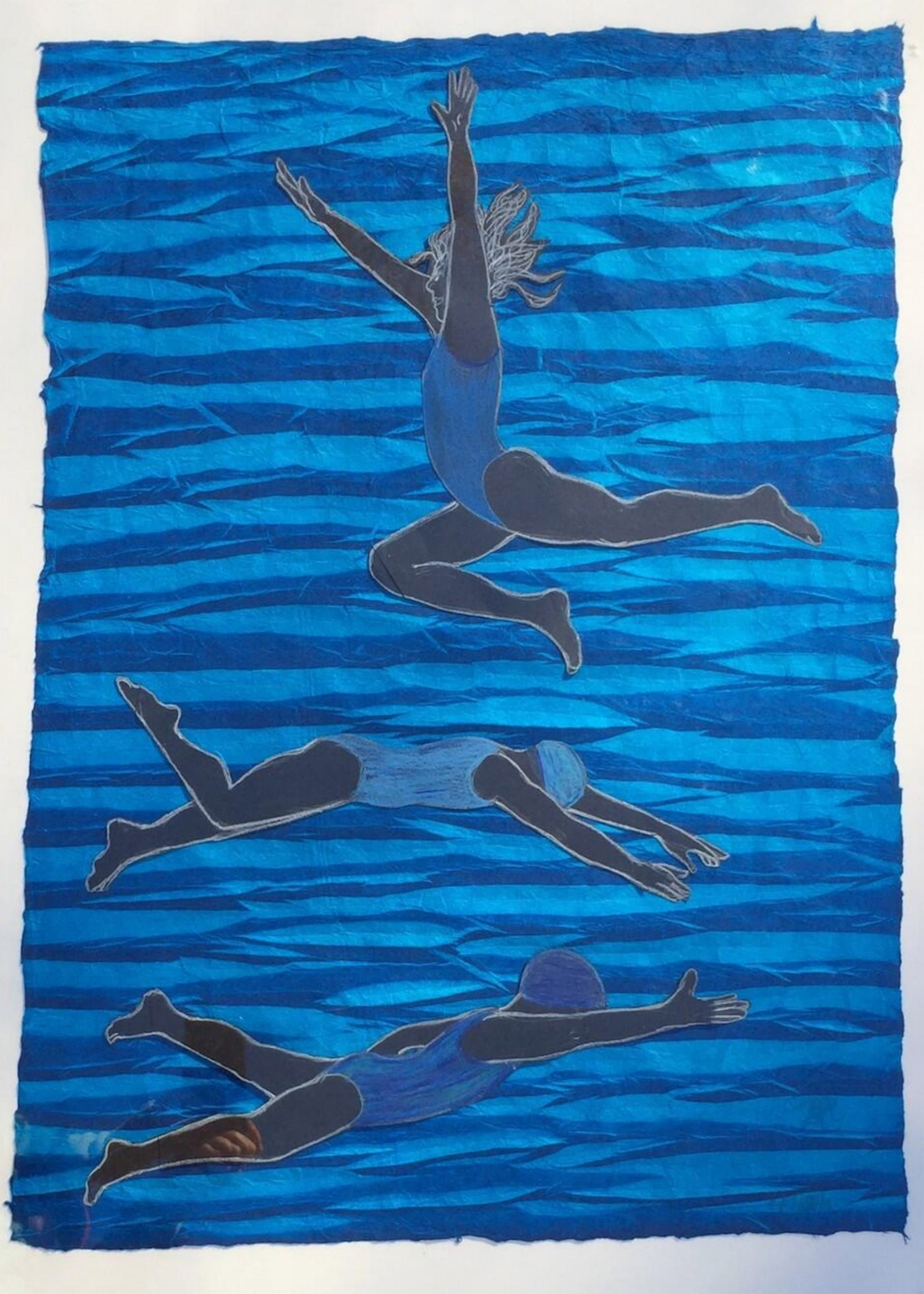

“Leap” by Marla Allisan, a clinical social worker for Harvard Law School. “I like saying I’m a part-time exhibiting artist. But I say it with great humility,” she added.

Harvard’s Common Spaces hosted a huge crowd — almost 400 people — for the launch last month of the first University-wide Harvard Staff Art Show. The venue was, like most everything these days, virtual. But that format came with a bonus: Unlike last year’s Smith Campus Center Staff Art Show, which restricted the artist pool because of limited wall space, this year’s show accepted submissions from all Harvard staff, featuring more than 280 artworks by 167 artists.

“There are so many people at Harvard who you work next to,” said Brianne Sullivan, an administrative assistant for Common Spaces, which helped organize the show, and an artist herself. “You see them walk into the office next to you every day for years and years and years, and you don’t know that they used to make pillows or they do watercolors.”

These days, walking into a co-worker’s office is an option only for essential staff who are properly masked. But even pre-pandemic, some people already worked in isolation — at Dumbarton Oaks, an art museum in Washington, D.C., and Villa I Tatti in Italy, for example. Mia Metivier, a program coordinator for the Harvard College Program in General Education and a painter and illustrator featured in the show, said, “This year, when we’re all more removed from each other than ever before, there’s an even greater need to create spaces to connect and engage with each other as ‘whole selves’” — what the show’s mission statement defines as “the artistic, creative sides that may not otherwise be a part of our work at Harvard.”

Or, as Sullivan put it, “We’re so much more than our day job.”

Roba Khorshid, an events coordinator in the Office of the Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Development and Diversity and a fashion designer, said that despite the diversity and number of submissions, she noticed a few common trends in the artwork: pets and backyard wildlife, trees both shadowy and bursting with color, flowers of paper, paint, wool, or real life, waterways and mountains, and portraits.

Several pieces address social movements and injustices: a leaf emblazoned with the colors of the pride flag; a video titled “Black Lives Matter” that documents experiences with racism; and a painting called “US,” which features immigrant faces looking out from behind the red stripes of an American flag.

Another binding theme, not surprisingly, was COVID-19. Two artists made their own masks: Marysara Naczi titled hers, “Don we now our plague apparel,” and Emily Ronald designed fabric versions of archaic plague doctor masks. In an acrylic painting titled “2020” by Maynor Campos, masked patrons visit a colorful Guatemalan marketplace. Despite the bright feel of the piece, the face masks and wan expressions show how “our lifestyle has been drastically changed,” wrote Campos in the description. And Mari Megias’ ink drawing “Pandemic” is a collection of floating faces, their mouths agape. “Pandemic rages,” Megias wrote in her caption. “We scream silently. Terror-laden yet empty eyes. But we are all connected.”

The massive 2021 virtual show was organized and run by 19 volunteers, many of whom were also participating artists. Khorshid, Metivier, and Sullivan all helped organize both this year’s show and last year’s Smith Campus Center Staff Art Show. Together, the committee collected the hundreds of paintings, sculptures, photographs, animations, documentaries, musical performances, textiles, and more into a virtual gallery space. Metivier also labored to make the virtual works accessible to all who attend the launch or visit the online gallery space by adding descriptive alternative text, closed captioning, and transcripts to all visual and video submissions.

The steering committee selected three of the artists to give short talks about their work before breaking into 11 medium-specific breakout rooms for more intimate conversations with artists. Those who preferred to stay in the main session participated in a docent talk. Volunteers like Metivier picked multiple pieces — including Desiree Guererro’s “WFH,” a miniature replication of her at-home work space — to discuss in detail with guests. One guest noted that the wallpaper in “WFH” looked like bars, “a beautiful prison.” “Our world has gotten smaller,” another said. Art, Metivier said, can be a vehicle to express sorrows or fears without feeling too exposed.

Perhaps the most memorable part of the launch was Securitas security officer Vincent Liu’s “trailer,” a four-minute-long animation featuring more than 100 of the show’s pieces: In it, a lime-green moth fluttered and launched from its page, a portrait of a young Black woman morphed into one of an older white man, and baby Yoda swung a light saber before a space ship burst out of the ground.

Desiree Guererro’s “WFH” is a miniature replication of her at-home work space. Mari Megias’ ink drawing, “Pandemic,” is a collection of floating faces, their mouths agape.

Since the pandemic started, Liu said, “We’re almost silhouettes of ourselves. We don’t really see each other.” But, he continued, coming together around a shared cause like art is a reminder that our 2D selves are only temporary.

“In the pandemic,” said Marla Allisan, a clinical social worker in CAMHS/HUHS for Harvard Law School, who participated in the show, “one of the things we are robbed of is the experience of witnessing each other and feeling witnessed, of feeling seen and understood.”

With the majority of staff working from home, behind computer screens, and tucked inside impersonal Zoom boxes, it’s even harder to maintain, let alone create, connections with colleagues. Sharing art, Allisan said, gives staff a chance to repair the injury to our community. For her, the show was a small but powerful way for staff to be seen.

As the virtual launch wrapped up — after an hour and only a couple of small technical snags — audience members asked for more time, so the organizers reopened the breakout rooms for another half-hour.

“We weren’t sure how it was going to turn out,” said Khorshid. “And it was better than anything we could have imagined.”

Clinical Social Worker, CAMHS/HUHS for Harvard Law School / Illustration and Collage

Marla Allisan never thought of herself as an Artist with a capital “A.” That title, she said, is reserved for Michelangelo.

“I like saying I’m a part-time exhibiting artist,” she said. “But I say it with great humility because I know there are many people who devote their lives to making art, who can wear that description with greater authority.”

Five years ago, Allisan walked into the Middle East restaurant in Cambridge’s Central Square and asked if they wanted some art for their walls. “That’s where I had my first one-woman show,” she said. To her surprise, people bought her work. Since then, she’s had more one-woman shows, one at the famous Politics & Prose Bookstore in Washington, D.C. Now, her work hangs on walls in Canada and Russia.

For the two pieces she submitted to the Harvard Staff Art Show, Allisan layered her fluid figures on colored papers. One piece — a figure with an arched back, mouth ajar, and just the ball of a foot touching the ground — was selected for a docent talk during the show’s virtual launch. Allisan enjoyed hearing the vast impressions that figure left: of joy, anguish, or pleasure.

While she missed the “tender” experience of showing her work in a more intimate in-person show, Allisan appreciated the virtual opportunity to connect and be “seen.” The show, she said, gave staff “a sense of deeper humanity, to not just see ourselves through an achievement lens.”

Public Programs Assistant, Harvard Graduate School of Design / Mixed Media

When Kat Chávez was born, she had a lot of hair. “Thick eyebrows. A ton of hair. Not your typical bald, hairless baby,” she said. Her father, who is of Mexican descent, said she looked like Frida Kahlo and the association stuck: Chávez grew up with the nickname “Katie Frida.”

Now, the Brown University graduate, who started her position at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in August 2020, has lived up to her nickname, at least in one sense: She’s a professional artist. Chávez rents her own studio in Brooklyn, N.Y., where she’s riding out the pandemic, and has been featured in 12 exhibitions, not including the Harvard Staff Art Show. Since she’s used to more-exclusive shows, Chávez said the staff show’s universal acceptance was “a really beautiful gesture of inclusiveness.”

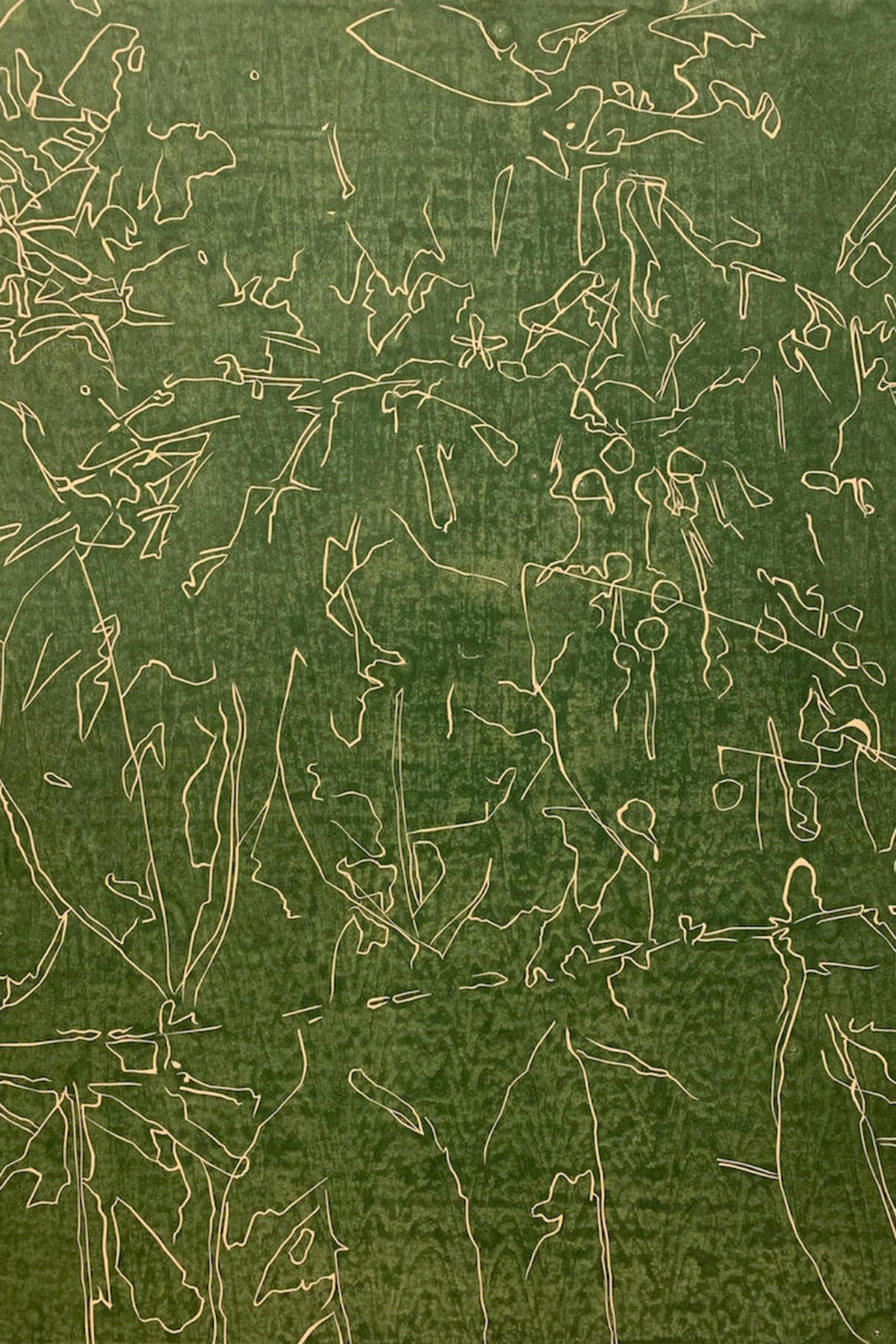

One of the pieces she submitted, called “Botánica Extraña,” is one of eight woodcut prints made as part of a community-oriented herbal healing project. Working with three community members, she researched which herbal remedies could alleviate their particular physical, mental, or spiritual ailment. Then she collected those herbs to use in a multilayer piece: herbs were overlaid to create a silhouette, which Chávez then printed and traced on wood blocks before carving them out and printing again. She likes to create “multiple translations” of her materials to get to know them, she said.

Chávez’s second submission, “Mirabilis Jalapa,” is, on the surface, a soft red bucolic scene. That “tender” presentation was intentional, Chávez said, but this piece has layers, too: The red dye she used, called cochineal, was harvested from insects that feed on the prickly pear cactus in Latin American countries. During the colonial period, painters in Europe used this dye in “magnificent paintings,” but the Indigenous workers who harvested it were either exploited or enslaved. Chávez is drawn to that conflict between beauty and violence and the imposition of European demands on Indigenous culture. Above her painted scene, she embroidered the plant Mirabilis jalapa (the marvel of Peru, or four o’clock flower): “mirabilis” is Latin, but “jalapa” has its roots in Nahuatl, an Indigenous language — it, too, is multilayered, both colonized and not.

Security Officer, Securitas / Digital Art & Animation

Four years ago, right after earning his master’s in teaching, Liu took a trip to Italy, where he lost his passport. Stranded and homeless, he met a former fine art professor-turned-street artist, who taught him how to make spray paint art.

“I didn’t do any sort of art before that,” Liu said. Afterward, he could do nothing but. “I dropped my teaching career and started to pursue this new passion.”

Liu started working for Securitas last March, right before nonessential staff left to work from home. But Liu is essential. Sitting at the Smith Center security desk, he enjoys the quiet — it gives him downtime in which to draw. Though he started out sketching portraits (during the virtual launch, he sat in front of a wall covered in hand-drawn portraits of characters from “Game of Thrones”), he quickly realized that he couldn’t make money from that genre alone. This past fall, he took a video-editing course through the Harvard Extension School, and for one assignment he had to animate a logo. And then he was hooked.

For the Staff Art Show, Liu submitted his final project for his video editing class, a two-minute animation called “Corona” that he described as “light-hearted … a distraction from the dismal mood of a precarious pandemic.” In the piece, a stick figure man walks through a pastoral scene until a looming cityscape rises behind it and a bottle of Corona beer explodes in his face. Chaos — including storm troopers, a swarm of bees, and more explosive Corona bombs — ensues. At the end, a message appears: “Stay safe. Stay healthy. Stay home.”

Liu also volunteered to create a trailer for the show, which animated more than 100 pieces of artwork. But he submitted a less light-hearted piece, too. Titled “Jehangir,” which means “king of the world,” the digital work is a tribute to a co-worker’s dad who recently passed away from COVID-19.

Liu wants to become a full-time animator. But no matter where he ends up, Liu said he wants to do something creative, “something that allows me to keep on progressing as a person and as an artist.”

Assistant to the Chair, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology / Collage

Five minutes before midnight on the last day to submit work for the Harvard Staff Art Show, Susan Kinsella sat in front of her computer. She still hadn’t submitted her work. She poured a glass of wine.

When she was young, Kinsella had loved to draw — mostly horses — and spent Sundays perched on the floor in front of the TV watching Jon Gnagy’s “Learn to Draw.” But her friend Toots Zynsky was also artistic, and as they grew Kinsella saw Zynsky eclipse her. Zynsky is now a professional glass artist with pieces worth hundreds of thousands of dollars in museums across the world.

“So, I wasn’t an artist,” Kinsella said. “Toots was an artist.”

Still, Kinsella was a maker: She sewed her own clothes, crocheted, and designed holiday cards. She worked for decades to draw the perfect cup of tea with steam rising off it (“I succeeded by 1972”). She wrote poetry, too, but when her kids were young, “Life got hard,” and she stopped. It wasn’t until they grew up and she moved to Somerville that she thought, “OK, I’ll start writing again.” But she didn’t; for some reason, her heart wasn’t in it anymore.

A gift certificate from a friend to Bead Works in Cambridge started her jewelry-making. To her surprise, people bought her designs. She ended up at Snow Farm, a residential craft school in Williamsburg, Mass., where she took metalworking to expand her jewelry skills until she heard an artist give a talk about collage: “This was art,” Kinsella said. “This wasn’t just drawing a steaming tea cup.”

That was five years ago. The same collage artist who gave the inspirational talk, who is now Kinsella’s teacher, recently met with her for a socially-distant chat about her artistic progress. As she looked over Kinsella’s recent work, she said, “You have a show here.”

“I started calling myself an artist three years ago,” said Kinsella. That admission felt powerful, but it doesn’t mean any step comes without doubt: At five minutes to midnight, Kinsella took a sip of wine, uploaded her two collages, and hit submit.

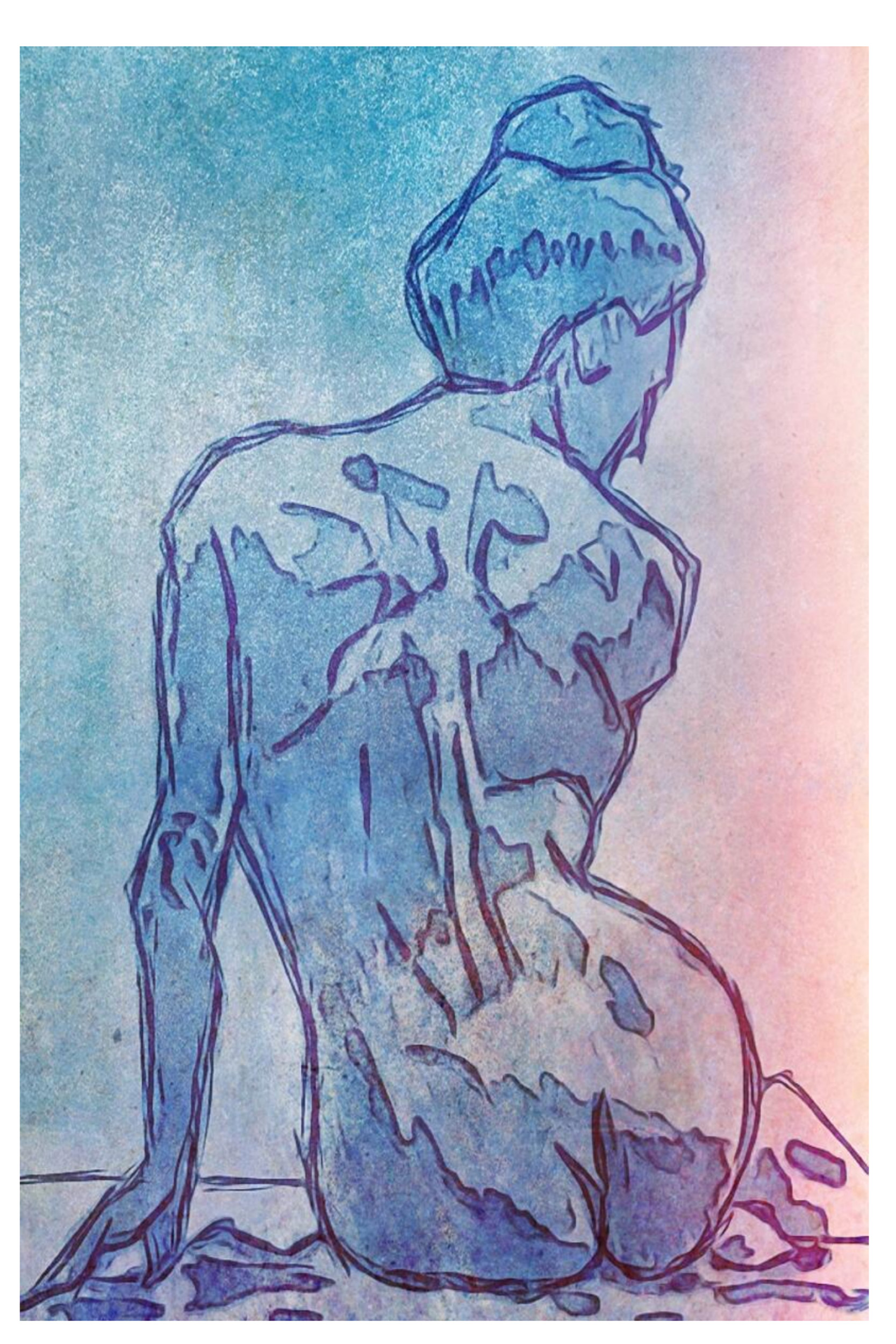

“I started calling myself an artist three years ago,” said Susan Kinsella, from the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology. A slightly cropped version of her collage “Summer.” Lab administrator Roel Torres’ “Study of the Back in Blue” was done during one of his figure drawing classes.

Laboratory Administrator, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology / Digital Illustration

When Roel Torres was a kid growing up in the Philippines, a comic book was a luxury, a treat his mother would buy him every now and then. Torres was still a kid when he and his mother moved to the U.S., so she encouraged his love of comic books, which were cheaper and more plentiful in the States. But soon Torres realized something: He could make his own.

Twenty of Torres’ 24 comic book projects have been published in the last four years. His stories have epic titles like “Rogue Agent Zed,” “Gladiasaurs,” and “Deathface Rocket Crew.” Recently, he contributed to a collection of graphic stories called BORDERx designed to spotlight the border crisis. Torres’ submission depicts heroes fighting racists. The project donates all proceeds to nonprofits that help border immigrants, such as the South Texas Human Rights Center.

But Torres didn’t submit any of his comic book artwork to the Harvard Staff Art Show; that, he said, works best alongside a narrative. Instead, he submitted two of the hundreds of figure drawings he generated in his three-hour-a-week, Cambridge-based figure drawing group. “The entire reason I do figure drawing is to be a more effective, more efficient, more proficient comic book creator,” Torres said.

A self-described extrovert, Torres has always craved connection and interaction. When he started making comic books he did so in isolation, but he found it lonely and desolate. “It was only when I found a community of like-minded individuals that I really found a joy in it.” For him, the staff art show was another opportunity to create community around art. As a break-out room host in the show’s virtual launch, he met Claudette Agustin, a fellow Pinoy and someone he never may have encountered otherwise.

“Even during a time when we’re all isolated and working at home remotely, art goes on and art remains important in people’s lives,” Torres said. “Four hundred people will gather to celebrate art and view art and the making of it.”

@HarvardStaffArtShow: https://www.instagram.com/harvardstaffartshow/

Visit the gallery: https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/staffartshow/gallery