Young adults hardest hit by loneliness during pandemic

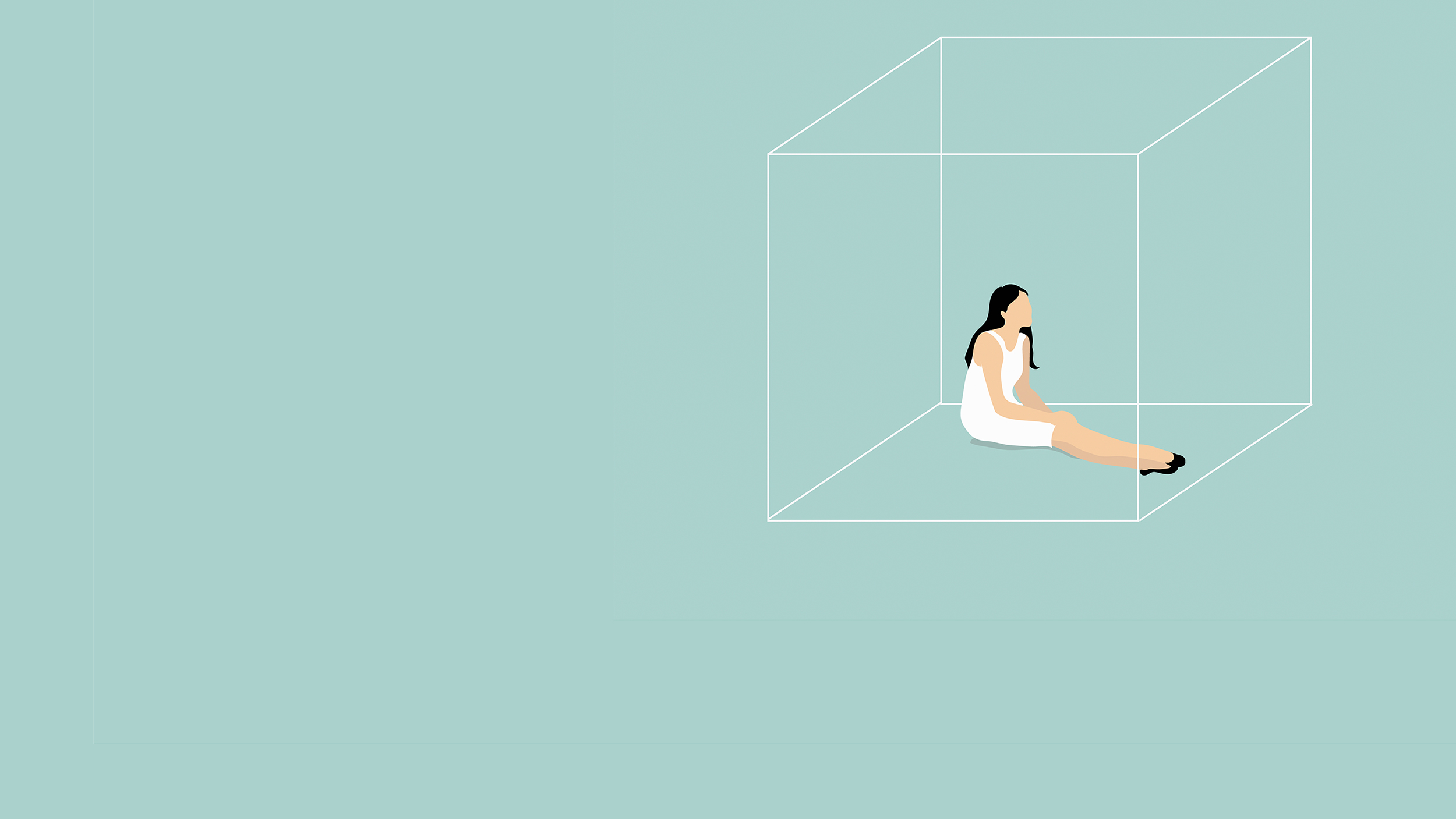

Illustration by Annalisa Grassano

Robust social network is key to easing pain, avoiding downward spiral, study says

As psychologists worry that the coronavirus pandemic is triggering a loneliness epidemic, new Harvard research suggests feelings of social isolation are on the rise and that those hardest hit are older teens and young adults.

In the recently released results of a study conducted last October by researchers at Making Caring Common, 36 percent of respondents to a national survey of approximately 950 Americans reported feeling lonely “frequently” or “almost all the time or all the time” in the prior four weeks, compared with 25 percent who recalled experiencing serious issues in the two months prior to the pandemic. Perhaps most striking is that 61 percent of those aged 18 to 25 reported high levels.

“I was surprised at the degree of loneliness among young people,” said Richard Weissbourd, a psychologist and senior lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) who helped lead the research. “If you look at other studies on the elderly, their rates of loneliness are high, but they don’t seem to be as high as they are for young people.”

The unsettling statistic is even more troubling when combined with June data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing that 63 percent of young people reported experiencing substantial symptoms of anxiety and depression. “It’s a group that we are really concerned about,” said Weissbourd, who suspects several factors are at work.

Older teens and young adults may be particularly susceptible because they are often transitioning from their “inherited families to their chosen families,” said Weissbourd, meaning they lack important connections to those who can “be critical guardrails against loneliness.” Students in college may be struggling to fit in and feel homesick, while those not in school can feel disconnected from important social groups or communities. Young people are also often making critical decisions about their professional and personal lives and relationships, which can add to the stress and sense of isolation, he said.

“If every person who’s in pretty good shape can make a commitment to reaching out to one person they are concerned might be lonely once a week, that would be a good thing.”

Richard Weissbourd, psychologist, senior lecturer at the Graduate School of Education

The new report also points to the way such feelings can lead to a downward spiral. Many young people who reported serious loneliness also said they felt as if no one “genuinely cared” about them. The survey also suggests that lonely people often feel they’re reaching out or listening to other people more than other people are reaching out or listening to them. “These things can become self-defeating,” said Weissbourd. “When you feel like you’re trying hard while other people are not trying hard, or you feel like you’re going to get rejected again, you withdraw, which increases your loneliness and your anxiety about social situations.”

Weissbourd and his team argue that eliminating loneliness requires a robust social infrastructure. Schools can be important points of intervention, they suggest, where teachers can be trained to connect parents to each other and to ensure every student is connected to a school adult. Doctors should also be asking about loneliness during annual physicals, helping connect patients who are struggling with social supports; high schools, colleges, and senior centers should focus on connecting young people with the elderly; and employers should check in with employees about whether they are lonely and provide them with resources that support connection. To further reduce the stigma associated with loneliness, the authors also recommend the creation of national, state, and local campaigns that stress the importance of maintaining social ties, and reassure those suffering that it’s OK to seek help.

“We need public education that removes the stigma of loneliness and really tries to alleviate the shame,” said Weissbourd, “because shame can also be self-defeating and cause you to avoid social situations or hide your true feelings in ways that make meaningful connections with others very hard.”

Weissbourd said he and his colleagues consider combating loneliness a moral imperative in an increasingly “hyper-individualistic society,” where many people often choose to focus on the well-being of their small circle of family and friends.

“We’re making the case that there’s a moral matter in terms of our community health, and that those of us who are in a position to do so should try to reach out to people who may be lonely. If every person who’s in pretty good shape can make a commitment to reaching out to one person they are concerned might be lonely once a week, that would be a good thing.”