In this Jan. 6 file photo, supporters listen as President Donald Trump speaks at his rally.

AP File Photo/Evan Vucci

What prompted Capitol rioters to violence?

New approach focuses on cognitive, emotional traits of the radicalized

When Donald Trump amassed 74 million votes in the 2020 election, it was natural that many of his supporters would feel deeply disappointed that Joseph R. Biden Jr., who racked up more than 81 million votes, was declared the winner. But Americans of all political stripes were stunned and horrified on Jan. 6 when several hundred Trump rallygoers stormed the U.S. Capitol hoping to stop Congress from certifying Biden’s victory.

Many of the Capitol rioters were extremists, according to the FBI and federal prosecutors. Some belonged to violent, far-right paramilitary and white supremacist groups, held anti-government views, or believed in political conspiracy theories.

Certainly, many Trump supporters felt anger over an election result they believed was illegitimate, yet only a tiny fraction responded that day in Washington, D.C., with violence. So what kind of person is moved to try to forcibly take over their own government? The answer may lie in the way people inherently think and respond emotionally to events, a growing body of research into the psychology of extreme political actors suggests.

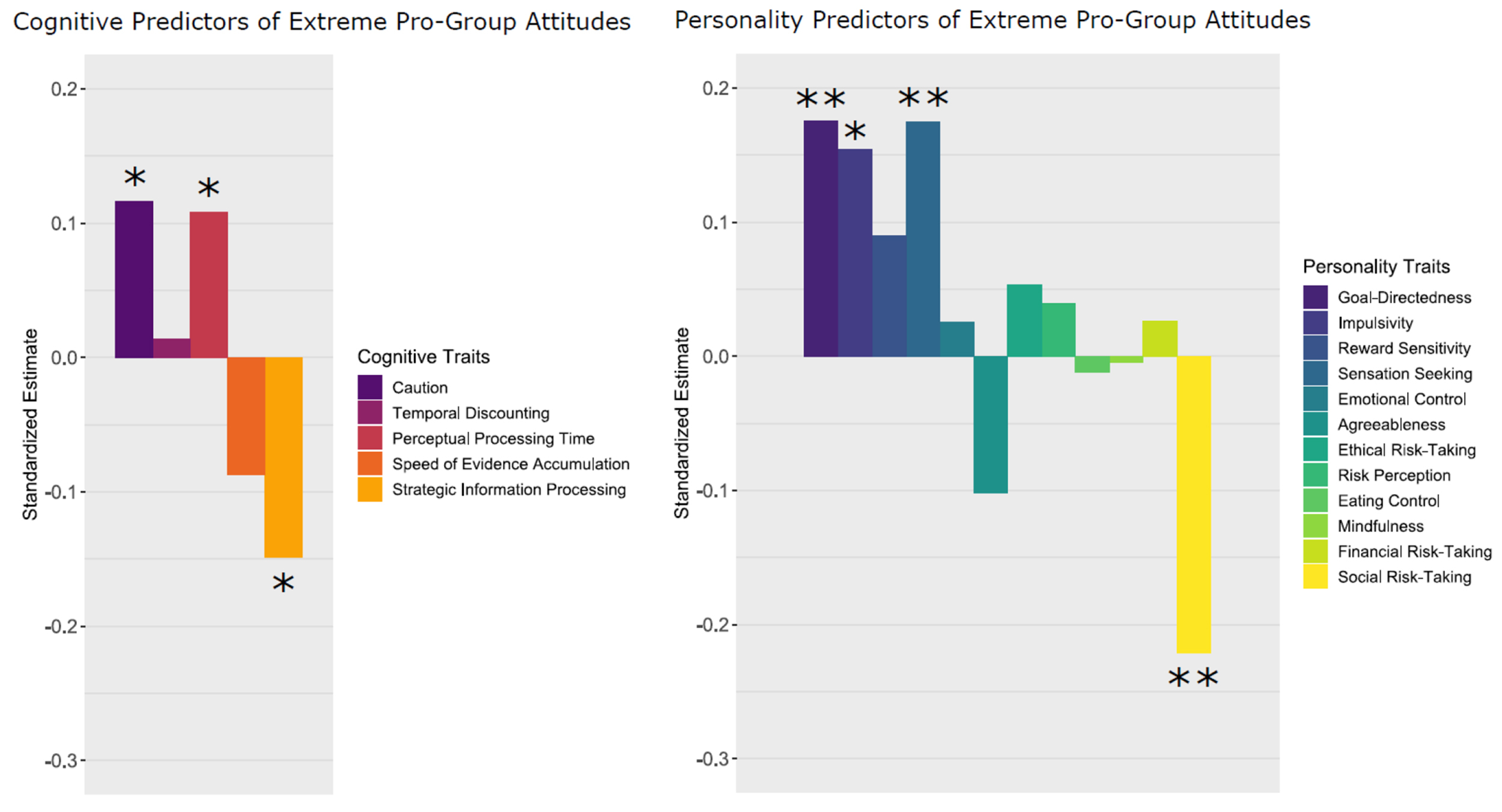

Those willing to endorse ideological violence share a number of underlying cognitive and emotional traits. In addition to being impulsive and sensation-seeking, they are “significantly” more likely to perform poorly on executive-function tasks that combine planning, problem-solving, and memory, and show little awareness of their own learning and thinking processes, according to a recent paper by Amit Goldenberg, a Harvard Business School psychologist, and Leor Zmigrod, a research fellow at the University of Cambridge and former visiting fellow at Harvard who studies why people become radicalized.

Amit Goldenberg discusses a new paper he co-authored that looks at the brain architecture commonalities of people who join and participate in extreme political acts.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

These cognitive and personality traits are more predictive of support for ideological violence than even demographic factors such as age, gender, and education level, Zmigrod’s research work has shown.

It’s part of a very new approach to the study of radicalization, one that departs from the usual focus on factors thought to best predict someone’s attraction to ideological violence, like social isolation, group identification, and the degree to which they are influenced by social norms.

“The way that this question has been asked before is: ‘Let’s look at the circumstances of the situation, the specifics, and the people related to it, and ask, why did these people decide to go and act?’” said Goldenberg.

“We try to ask something slightly different, which is: ‘What are the personality characteristics about the way that people behave in the world unrelated to politics — the way that they think, the way that they respond emotionally to events — that predict whether they’re more likely to behave in an extreme way in the context of political actions?’” he said.

People who have trouble adapting to new, changing intellectual demands or circumstances, known as cognitive rigidity, tend to hold more ideological and dogmatic views about politics, nationalism, and religion, for example. That inflexibility is also predictive of a greater willingness to endorse violence in support a political group and a strong belief that they would sacrifice their own life to save other members of the group, according to the paper, forthcoming in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

All of this helps explain the appeal to certain individuals of extreme ideologies that offer simple, unambiguous explanations of complex ideas and events, often found in conspiracy theories and other forms of “fake news.”

Whether any political persuasion is more or less prone to violence than another is not yet known, said Leor Zmigrod, a former visiting fellow at Harvard who studies why people become radicalized.

Courtesy of Leor Zmigrod

“One of the things that drives the spread of fake news is ‘cognitive laziness,’” a term associated with MIT scientist David Rand, Ph.D. ’09, to describe a person’s inability to engage in cognitively challenging situations, Goldenberg noted.

“And that’s not the obvious thing you would think. The obvious thing you would think is that people are just likely to see the reality through the lens of their political affiliation and be motivated to see fake news as real because it’s congruent with what they want it to be,” he said.

Stoking anger has long been an effective tool of political parties and politicians on the left and right to spur supporters to action, from registering to vote to making a campaign contribution. How strongly a person reacts emotionally to events in general, as well as his or her ability, or lack thereof, to regulate those emotions, is also a predictor of whether a person is willing to take extreme political action.

Many Jan. 6 rioters, upset that Biden was to be declared president-elect, characterized their presence at the Capitol to reporters and on social media as a righteous effort to prevent the presidency from being “stolen” from Trump, often comparing themselves to American colonists revolting against the British occupation of 1776.

Regressions predicting individual differences in extreme pro-group attitudes, using (A) cognitive tasks and (B) personality surveys as the predictors. (*p<.05, **p<.01.) Adapted from “A Data-Driven Analysis of the Cognitive and Perceptual Attributes of Ideological Attitudes.” (2020)

Leor Zmigrod, Ian Eisenberg, Patrick Bissett, Trevor Robbins, Russell Poldrack

Given how often human beings are “mistaken” about why they do things, Goldenberg said such statements, especially those made on social media, were more “signaling efforts” designed to reach others in the far-right media ecosystem than actual explanations of their motivation for storming the building.

“We also seek moral justifications for decisions that were impulsive and made because of emotions we felt at the time,” he said. “These explanations provide us with a good outline of the social norms that these people are in and what is considered moral and good” and therefore “are important pieces of information for us to understand.”

For over a decade, federal law enforcement agencies have identified political extremists as a growing security threat. On Wednesday, the Department of Homeland Security’s National Terrorism Advisory System warned of a “heightened threat” from domestic violent extremists, some of whom are “ideologically-motivated” to incite or commit violence well into 2021.

Whether any political persuasion is more or less prone to violence than another is not yet known. Zmigrod said no large-scale statistical data is available regarding how the willingness to endorse ideological violence relates to various political ideologies.

Though there is still much to learn about radicalization, she and Goldenberg hope this research highlights the complex array of political actors that exist and shows the different psychological pathways that can lead people to embrace extreme political action.

“Appreciating the diversity of origins and manifestations of ideological extremity is essential in order for identifying it in the first place and understanding the reasons some individuals are more vulnerable and susceptible to engaging with ideologies in an extreme way,” said Zmigrod.

It’s also valuable information for policymakers and others who seek to craft counter-extremism initiatives that try to prevent radicalization. This research suggests that interventions that address an individual’s psychological traits, such as cognitive flexibility, intellectual humility, and emotional regulation, “will be more comprehensive and informative than interventions that focus on demographics or even ideology alone.”