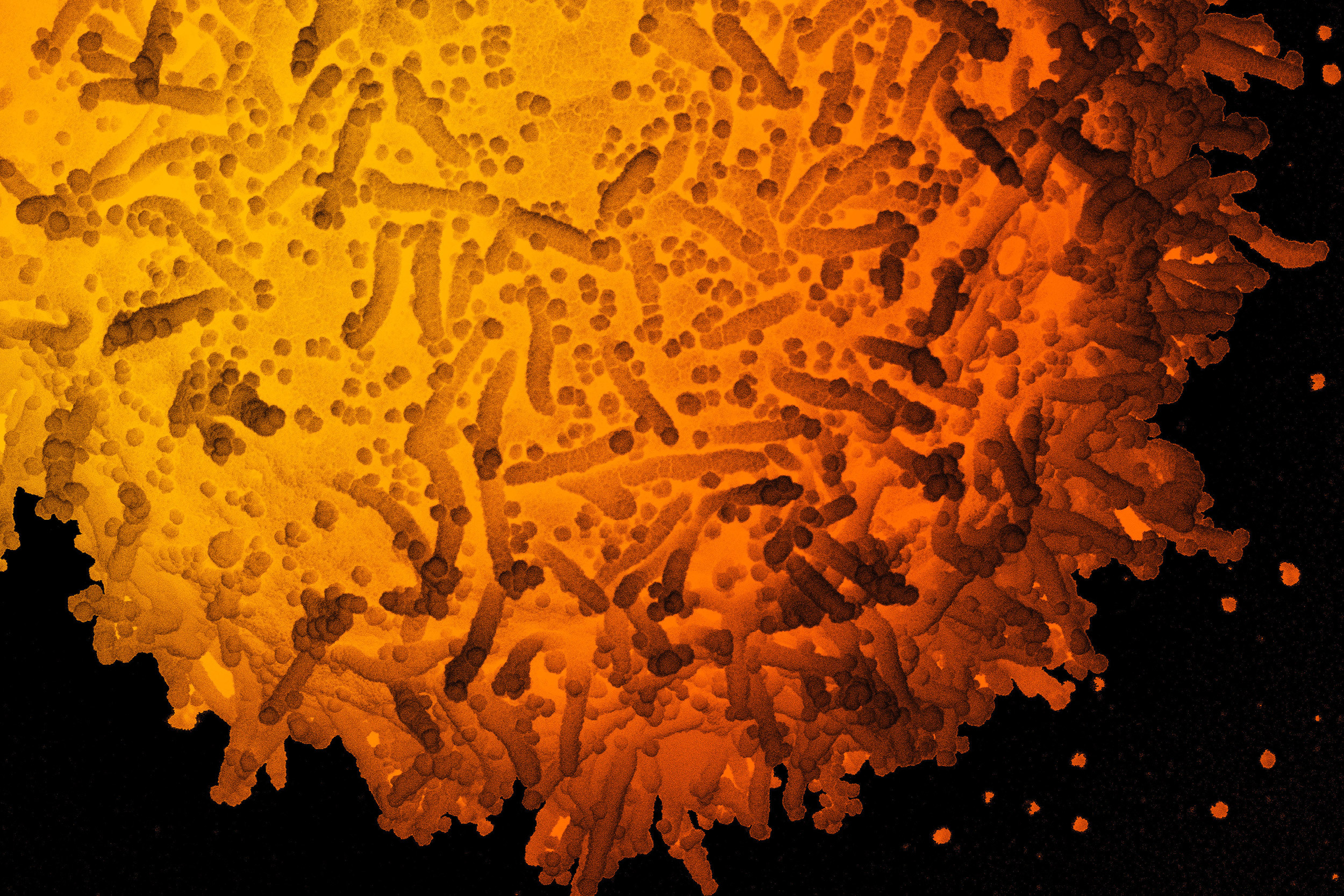

A color-enhanced image of a cell infected with SARS-CoV-2 particles, isolated from a patient sample. SARS-CoV-2 virus particles are the small, roughly-spherical structures, found on the surface of the cell, which is exhibiting elongated, rod-shaped cell projections.

Credit: NIAID

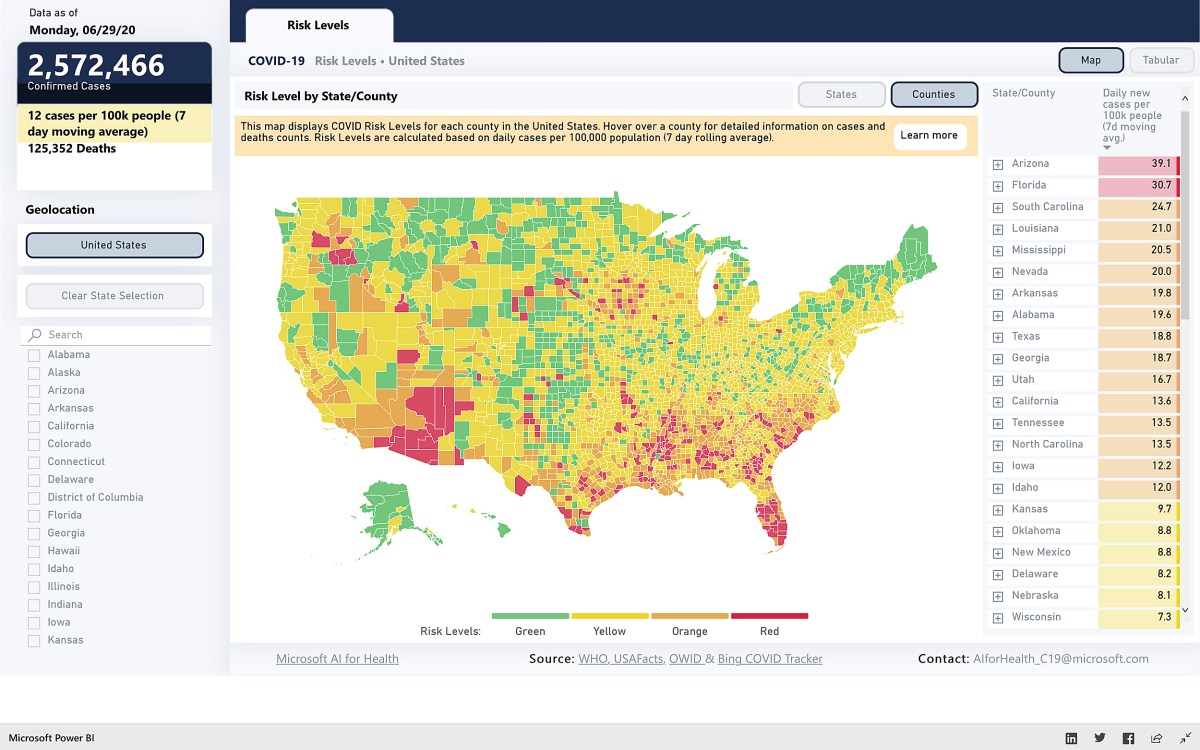

Highly infectious coronavirus variant dampens prospects for summer return to normal

Experts say it raises need to speed vaccinations, lifts herd immunity threshold

Harvard public health experts say a more contagious British variant of the COVID-19 virus now spreading in the U.S. has tempered expectations that vaccination efforts would mean a return to normal life in the coming months and ratcheted up pressure to speed inoculations, which have gotten off to a disappointingly slow start.

Epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch, director of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, said though he had been skeptical that vaccination would quickly bring the pandemic under control, he had thought that the campaign’s progress, coupled with warmer weather bringing people outdoors, meant that relatively normal activities could resume by summer. But with experts estimating that the new variant will spread significantly faster than the original, Lipsitch said he’s less certain.

“Before the new variant I was more hopeful of a summer that would allow people to go to camp and travel and that sort of thing. I’m less sure about that now,” said Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology. “That just makes this a much harder problem. … It’s certainly not good news.”

Another variant from South Africa has also emerged and is raising additional concerns among public health officials because it appears to have some worrisome characteristics but less is currently known about it.

The emergence of the British variant here heightens the importance of rapid vaccination, Lipsitch said, and makes public health control measures, such as masking and distancing, more important and more likely to be needed longer. Rollout of vaccines in the U.S. have been snagged by shortages, delays, and bureaucratic snafus. The Trump administration predicted in December that 20 million people would be inoculated by the end of the year, but as of Wednesday only 5.3 million had received the first of two required shots, according to a Centers for Disease Control tracker.

The increased infectivity of the British variant means that, should it become widespread here, contacts would need to be cut back by an additional third just to keep spread where it is now, a tall order in a nation that has had difficulty controlling the original virus. On Wednesday, the pandemic set another grim milestone, marking a record 3,541 deaths, according to the CDC, and bringing total U.S. deaths to 365,005. Cases rose to nearly 21 million, according to the government tally.

“It’s a big deal for a world that is already stretched trying to control the old variant.”

Marc Lipsitch

Lipsitch said it makes sense to focus contact tracing efforts on the new variant, as a way to keep it in check and delay its spread for a few months, when warming weather will become an ally.

“It’s a big deal for a world that is already stretched trying to control the old variant,” he said.

Though the British variant has spread rapidly through the U.K., it does not appear to cause more severe illness and seems as susceptible as the original to vaccine protection. It has been detected in dozens of countries, including several locations in the U.S. Though the numbers of U.S. cases have been low, given the difficulty the U.S. has had in containment efforts, there’s no reason to think this new variant won’t soon be widespread, Lipsitch said. Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker echoed that thinking on Tuesday, saying, that though the variant has not yet been detected in Massachusetts it’s reasonable to think it is already here, according to media reports.

British scientists, meanwhile, on Wednesday fine-tuned earlier estimates of the variant’s infectivity, saying in a yet-to-be peer-reviewed-study that it appears to be 56 percent more transmissible than the original virus. Rapidly rising case numbers have prompted the British government to reimpose a nationwide lockdown, halting in-person learning at schools and colleges and asking residents to stay home except for essential tasks.

Scientists say it’s not surprising that variants to the original virus would emerge but are keeping an eye out for those that have particularly challenging characteristics. Infectious disease expert Barry Bloom, who joined Lipsitch on a media conference call Tuesday, said a South Africa variant potentially worries him more than the one from Britain.

“There’s very little data that I can find in any publication — mostly in news reports — that suggest, in contrast to the English one, that [the South African strain] may be less neutralized by antibodies from convalescent patients…. That would not be a good thing,” Bloom said.

Former Food and Drug Administration chief Scott Gottlieb told CNBC on Tuesday evening some experimental evidence from a lab at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle suggests that variant may “obviate” antibody drugs.

Bloom also said that the emergence of the more-infectious British variant means a higher percentage of the nation’s population will need to be vaccinated to reach herd-immunity level, at which enough people are immune to the virus that it interrupts spread. What the new threshold is remains unknown, Bloom said, but he pointed to recently rising estimates from Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases and an adviser to both President Trump and President-elect Biden, who told the New York Times in late December that it likely will be between 70 and 90 percent.

A significant factor in the uncertainty is the fact that, though the two vaccines approved for U.S. use prevent severe disease, how well — or even whether — they prevent transmission is still unknown. Bloom, the Joan L. and Julius H. Jacobson Research Professor of Public Health, pointed to the example of the polio vaccine, which prevents illness but doesn’t prevent the virus’ spread — in polio’s case through the feces — which has made it difficult to eradicate globally. In case of SARS-CoV-2, Bloom said, it is likely that vaccinated individuals will have lower, possibly much lower, levels of virus in the nasopharynx, from which it can be exhaled, making them less infectious, but that has not yet been proven.

Though vaccines are slowly rolling out, Lipsitch said the new British variant likely will make the coming winter months, which were already expected to be difficult, even worse than anticipated. By spring and summer, however, though transmission will likely still be widespread, vaccination of health care workers and those at high risk may mean the pandemic’s worst effects are “blunted a lot.”

“Assuming no negative surprises with the vaccines and expecting that there will probably be more vaccines approved or authorized in the coming months — the vaccines really are a huge change for the better — I think that will be our way out, but I think the new variant doesn’t help with that,” Lipsitch said.

Lipsitch said that even if we don’t end up eliminating the virus, vaccines may effectively prevent severe illness in vulnerable populations while the virus continues to circulate among those more likely to have mild or asymptomatic illness.

“My suspicion is the way we will get out of the crisis that we’re in is not by halting transmission of this virus, but by defanging it effectively,” Lipsitch said, “in other words by protecting enough of those highly vulnerable people so that even if there is transmission that’s going on it is not causing so much destruction of human lives and to the medical system.”