Giving the Constitution a grade of C

Law prof and writer explain it all in primer for young readers — and older ones, too

Illustrations by Ally Shwed

Children’s book author Cynthia Levinson and her husband Sandy Levinson, a constitutional scholar and a Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, have recently published “Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Graphic Novel,” based on their 2017 constitutional law primer for young readers. That first book, “Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws that Affect Us Today,” deals with weighty issues such as the Electoral College, gerrymandering, voting rights, and political imbalance in the Senate. The Gazette interviewed the husband-and-wife team to talk about the flaws in the Constitution and the need to start a dialogue about constitutional change to make the U.S. “a more perfect union.”

Q&A

Cynthia and Sandy Levinson

GAZETTE: How did the idea of writing a graphic novel about the Constitution come about?

CYNTHIA: It actually was the person who developed the Discussion Guide for the original text version of our book, put out by Peachtree Publishing Co., who came up with the idea and suggested it to Mark Siegel, who leads First Second Books, a graphic-novel publisher in New York. The idea wasn’t ours, but as soon as it was brought to us, we were way onboard. We were just thrilled with the idea.

SANDY: I believe that Americans in general know appallingly little about the actualities of our political system, and this all begins at the secondary school level. I can testify that most law students and most lawyers have a deficient knowledge of the kinds of things we write about. Much of my eagerness to participate in these kinds of books, which certainly are very different from what I ordinarily write, is the belief that it’s important to educate kids because if you wait until they’re all grown up, it’s kind of hopeless.

GAZETTE: What was the main challenge in writing this book for both of you?

CYNTHIA: The challenges of writing the text version of the book had to do with deciding which topics to focus on. In the book’s second edition and in the graphic-novel version, we have 20 fault lines we write about. But really the biggest challenge was keeping the book updated and current. The news is ongoing and always so related to the Constitution that it was like building the plane while flying it. Transforming the textbook into a graphic novel was actually not so challenging as I had expected, largely because the illustrator Ally Shwed did such a terrific job.

SANDY: For me, the challenge earlier was to accept the fact that I really can’t write for kids and Cynthia can. [Laughs] I couldn’t write for that audience if my life depended on it. In genuine seriousness, it’s very important that Cynthia is a prize-winning children’s author, independent of the fact that she happens to be my wife, and she has demonstrated that she knows how to write for the audience we wanted to reach. The paradox is that I’ve actually used the print version of our book, on which the graphic novel is based, in classes I’m teaching this semester at both the Harvard and Yale Law Schools, and students at both of those places have agreed that it’s very accessible. My own view is that our book is written for children of all ages, including grandparents.

GAZETTE: Before we talk about the flaws in the Constitution, what are the Constitution’s main strengths?

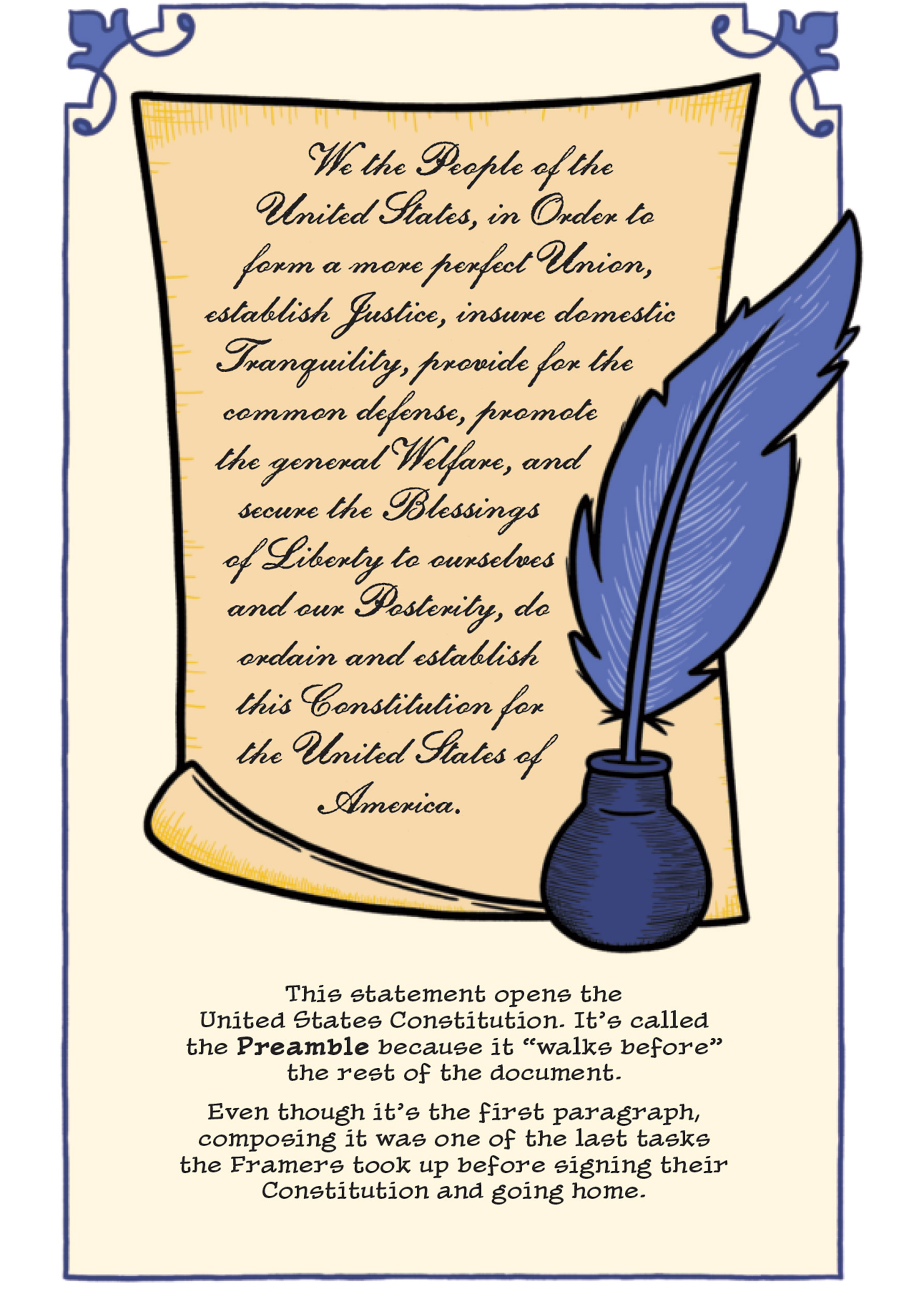

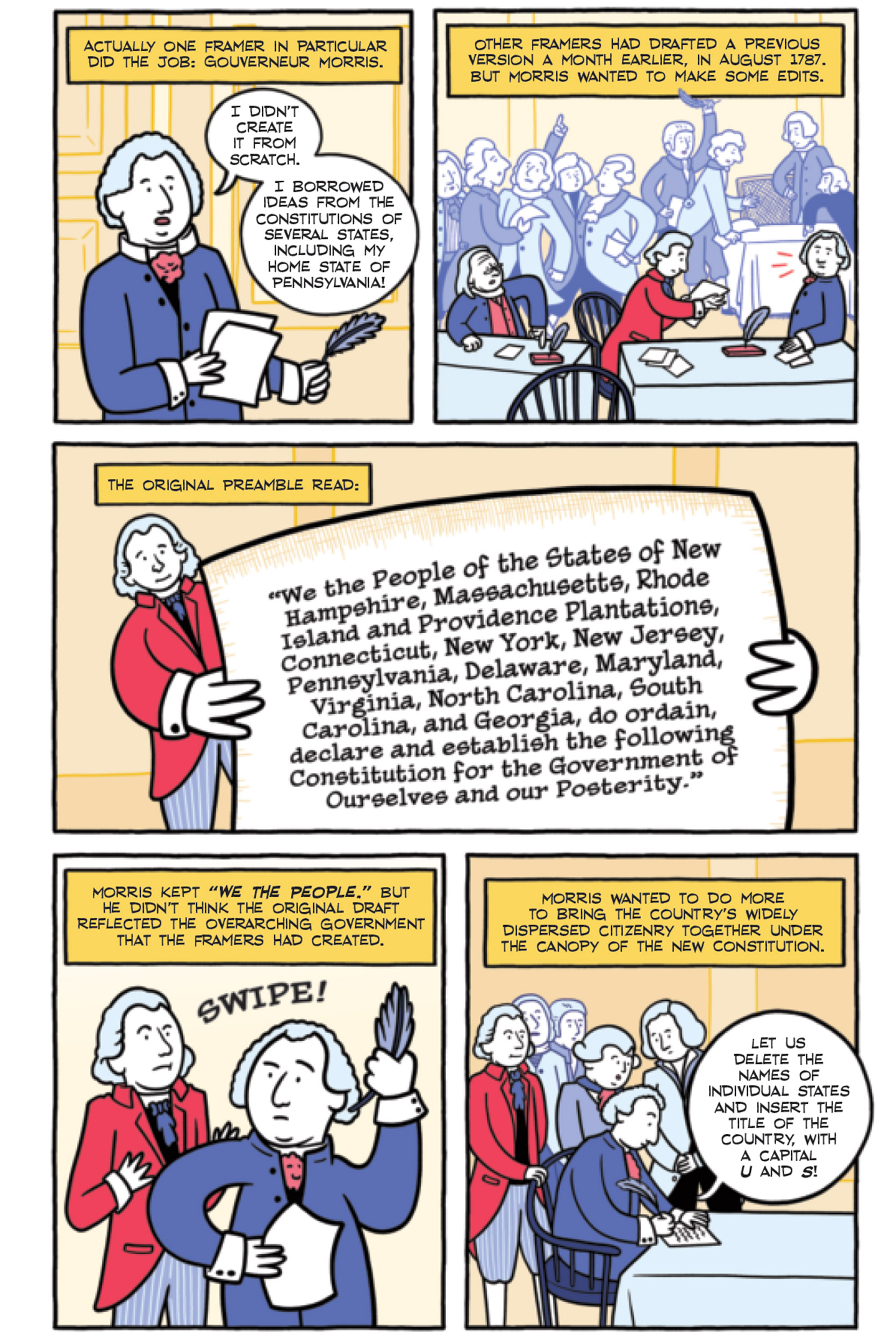

SANDY: We both agree that the main strength is the preamble. It’s a wonderful preamble because it tells you concisely what the point of government is.

CYNTHIA: I would add that the Constitution as a whole was an incredible invention. It wasn’t made up of nothing. The framers were looking back at Parliament, and also possibly looking at Indigenous peoples’ forms of governance as inspiration. They created a new type of government that is flawed and hasn’t stood up well over time, but they managed to keep the colonies as one country. It did unravel later on, but for some time, they managed to put together, under one umbrella, a government, and when the first Congress took place, all of the representatives and senators swore an oath to the Constitution of the entire country.

GAZETTE: What was the influence of the five-nation Iroquois Confederacy in the formation of the new government? Your book mentions that the Iroquois had three bodies similar to an executive, a legislature, and a court system, and that their treaties began, “We the people.”

SANDY: For years and years, the possible influence of the interaction of white settlers with Indian tribes was ignored. In more recent years, there has been an active desire on the part of some scholars to say that white settlers really were influenced by the way the Iroquois Confederacy had organized themselves. I doubt that it was a major influence, but it would not surprise me at all if it registered on some of the people who did have active experience with the Iroquois. It is important to realize that could have been the case. But it’s a matter of debate.

One of the things that we always emphasize is that we do not engage in founder bashing. I agree with Cynthia that the people in 1787 [the year the Constitution was written] were doing the best they could, given what they knew and the political circumstances of 1787. The people we bash are ourselves because we don’t have the same kind of willingness of the framers to think and act audaciously with regard to reforming a political system that has real problems. The framers described the existing political system as “imbecilic,” and instead, we have this reverence towards 1787, which I think the framers would be astonished and even appalled by.

GAZETTE: You both have said that seeing the Constitution as a sacred document is a double-edged sword because it doesn’t allow a national dialogue about the flaws in the Constitution. How can we overcome this problem?

SANDY: If one treats the Constitution as a sacred text, then it becomes blasphemous to suggest that the framers were human beings, instead of demigods, and that we should emulate them by engaging in genuine reflection and choice about how we want to be governed. One of the most important things our book does is to compare the U.S. Constitution, not only with other constitutions around the world, but also American state constitutions. Most Americans don’t even really know that there is a state constitution. If they do know, they treat it instrumentally. Their hearts don’t beat faster. State constitutions are often amended; they’re even replaced. If you look around the world, you discover that constitutional reform is quite frequent. Most Europeans do not have this kind of sacrosanct view of their constitutions. I think that it’s very important to be more instrumental and stop treating the Constitution as a sacred text.

GAZETTE: What do young readers who read your book learn about the Constitution that they wouldn’t find in other books?

CYNTHIA: Civics education, to the extent that it exists, tends to be fact-based, such as we have a bicameral legislature; we’ve got a three-part government; and here’s how a bill becomes a law. Largely, most young readers are in a state of not-deep knowledge about the Constitution. I would like to think that our book does a good job in connecting the dots between the Constitution and what’s going on today. I hope that our book helps young readers learn the implications and the ramifications of what happened in 1787 to issues we’re debating today such as habeas corpus, freedom of speech, voting rights, and gerrymandering.

GAZETTE: Your book focuses on 20 flaws in the Constitution. Which ones concern you the most?

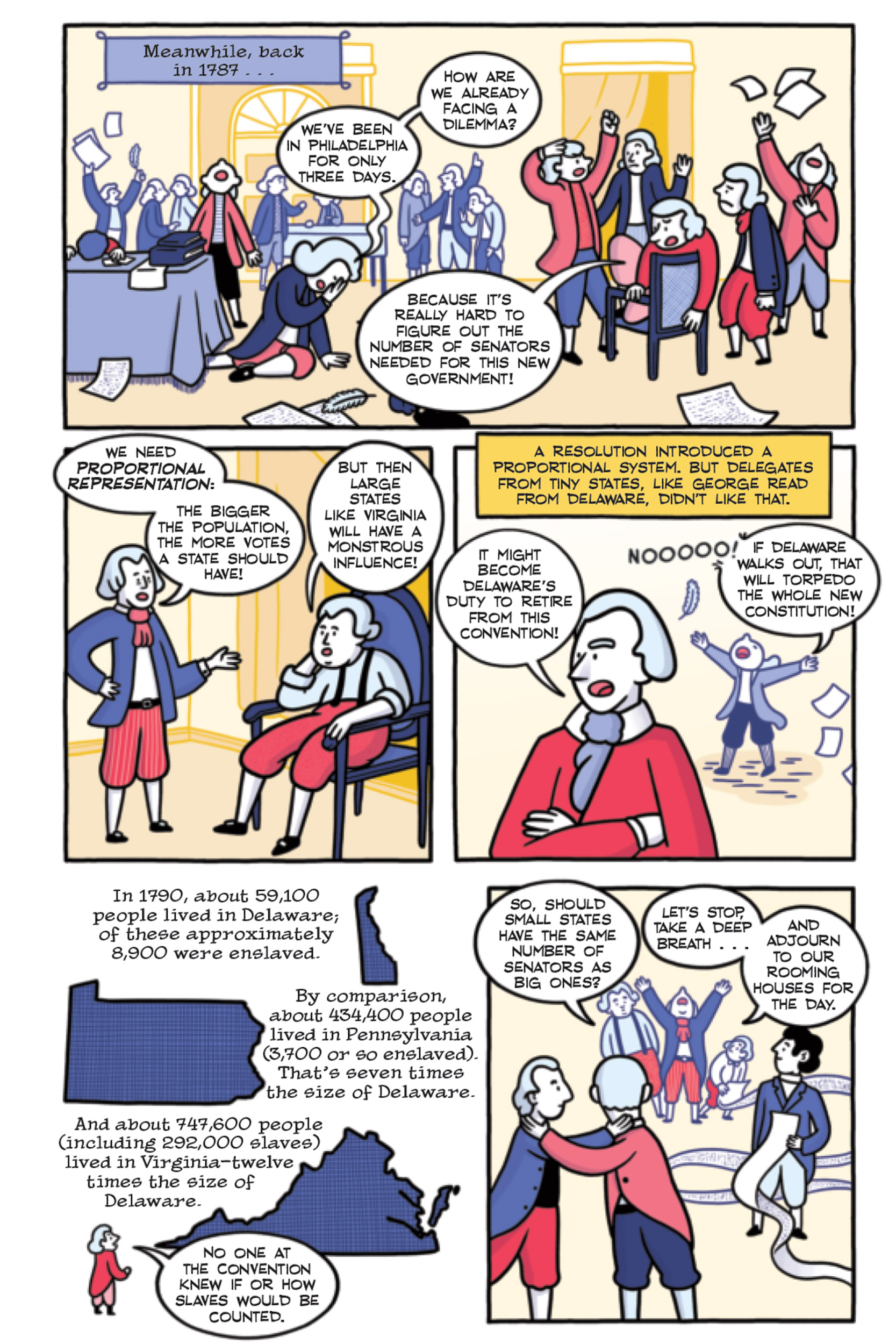

CYNTHIA: Many people, especially right now, would point to the Electoral College or gerrymandering. For me, the biggest problem we’re living with today is the Senate and its lack of proportionality regarding population. We’ve got a bicameral legislature; a House represented with proportional representation and a Senate with two senators per state. The more urbanized our country becomes, the more concentrated the population becomes in urban centers, leading to a number of less-populated states. The fact that Wyoming, for instance, has two senators and South Dakota has two while California, Texas, New York have two senators each makes no sense at all. I think it is totally destructive to our system. It’s just completely out of balance.

SANDY: In our book, we include a graphic that shows that more than 50 percent of the U.S. population lives in nine states, which means they get 18 senators while the other less than half of the American population lives in 41 states and they get 82 senators.

Right now, what most really worries me is the fact that, thanks to the 20th Amendment of the Constitution, Donald Trump will be president until Jan. 20, 2021, even if he is soundly defeated, which I think he will be. If you look around the world, this is a very long period between repudiation and actual loss of office, and that could be a genuine menace to the United States and to the entire world. Most of the time, Inauguration Day isn’t that important. Right now, the fact that this person could be president for roughly 11 weeks after being soundly repudiated, I think should frighten each and every one of us. And that is a constitutional fault line.

GAZETTE: Why do you give the Constitution such a low grade?

CYNTHIA: It’s harsh, I know. We give the Constitution a C. We use the preamble as what educators think of as a rubric. We go through each bullet point of the preamble looking at the past and why those values were important to the framers. Then we define them for our current situation and look at how well those values are being met now. Having come to a deeper understanding of how severe the imbalance in the Senate is, or the Electoral College, or gerrymandering, or voting rights, and how tumultuous all that makes our country, I don’t think anything has improved, but that grade is an indicator of the extent to which the Constitution has served us well and not well, that is, basically OK. We have pretty much reconstituted ourselves since the Civil War, but not in a stellar way; not something to be proud of.

SANDY: I would probably be even a harder grader than Cynthia. I’ll give it D + or C-. It’s now been some years since the United States Congress has had an approval rate above 20 percent. Usually, it’s somewhere between 12 and 15 percent. If you ask people, “Is the country going in the right direction or the wrong direction?” roughly two-thirds, quite consistently, say it’s going in the wrong direction. Is it fair to say that the Constitution deserves some blame for this lack of confidence? The answer is yes. One reason that Congress is generally held in contempt is because wherever you are in the political spectrum, left, right, or center, you cannot really believe that Congress is going to respond effectively to most important problems challenging the country. If you’re on the right, you will be frustrated and angry because they haven’t gotten rid of Obamacare. If you’re on the left, you’ll be talking about climate change or the DACA program. And if you’re in the center, you might be talking about getting some control on medical spending. But Congress is doing none of this. And that doesn’t bode well for our future. I don’t mean to say that the Constitution is a failure, but it’s in trouble. It’s similar to when you’re teaching a child, and you would say to his or her parents, “Your kid has real potential, but there are these problems you ought to know about.” Americans ought to think much more about these constitutional problems than they do.

GAZETTE: What are the ways to deal with those problems in the Constitution?

SANDY: In my view, only a constitutional convention is likely to be able to address the broad array of issues that interconnect with one another. A few things could be discussed in isolation, but a lot of things really are connected as the thigh bone is connected to the hip bone.

CYNTHIA: Most people who are opposed to a constitutional convention, like me, fear it because it’ll be a runaway convention where everything will be up for grabs. But most of my concerns have to do with the process. How would we choose the people who would go to a constitutional convention? Would it be like the Senate, with one or two people per state, or would it be proportional? How would we select them for various demographic representations and for political perspective? I think we would get into so many arguments and so much tension just over the construction of a convention that I’m not convinced that it’s worth entering into. In terms of other things that we can do, we believe that are specific steps we can take with each one of the fault lines we list in the book. For instance, there are work-arounds for the Electoral College; Senate rules can change; laws can be passed. It’s a hodgepodge. It’s not a carefully quilt-constructed approach; it would have to be kind of a laser target on this problem and a laser target on that problem. It would be a long and complicated process, which is probably why Sandy thinks that a convention would be preferable.

SANDY: If you look at a number of countries around the world, you’d discover that significant constitutional change takes place after catastrophes. World War II led to new constitutions in Germany and Japan. The breakup of the Soviet Union was not a catastrophe from our perspective, but it was an event that generated a lot of constitution writing in Central Europe. Sweden reformed its constitution in 1972, and nobody took notice of it. The real challenge, frankly, is whether we in this country can think seriously about constitutional reform prior to catastrophe. I don’t have any great confidence that the answer is yes. It may take a much worse catastrophe even than we now face to get people to say, “Well, maybe the Constitution itself needs significant revision.”

GAZETTE: What are the main lessons your readers could take from your book?

SANDY: The main lesson I would like readers to take away is to realize that what they might believe are dull and boring issues are in fact extremely important. For instance, it takes two-thirds of each house of Congress to override a presidential veto, which is important because presidents win literally 95 percent of all veto contests. That would be my chief takeaway: Structures are important; they are not dull and boring.

CYNTHIA: I would like readers to believe that they can play a role. Yes, talking about the Constitution is interesting, but there are things that can be done. We have an example of a student who got an amendment passed over 200 years later. Now that’s not likely, but there are other ways of taking action, and we list a number of them. We would like young readers to not feel helpless at all.

SANDY: We have a chapter in the book that focuses on a college student from Michigan, who was able to mobilize the voters to amend the Michigan constitution in directions that we probably wouldn’t have voted for. But that represents citizen democracy. And that’s one of the things that I hope we teach students and their grandparents. In a lot of states, there is the possibility for direct citizen decision-making that is completely absent at the national level. At the very least, people should talk about whether the Maine Constitution or the California Constitution is a better constitution, and argue about that. You don’t even have to compare the U.S. Constitution and the German Constitution. You can read about the Massachusetts Constitution, or the Pennsylvania Constitution and argue about which is better or worse. For me, that would be just huge progress.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.