A fall 2019 JusticeAid concert in New York.

© Evy Mages Photography

In the name of justice

In the battle against systemic racism, these alumni chart different courses for change

Mentoring young Black men to become tech leaders. Using the power of music to support emerging social and racial justice nonprofits. Marshaling local communities to fight racism and inequity in health and medicine. Christina Lewis ’02, Stephen Milliken ’73, and Michelle Morse, M.P.H. ’12, are among the thousands of alumni who are leading organizations and spurring progress in their communities at a time of historic change. The three spoke recently with the Gazette about how to address urgent and unmet needs, the experiences and people who inspire them, and the lessons they’ve learned — and the hopes they have for the change yet to come.

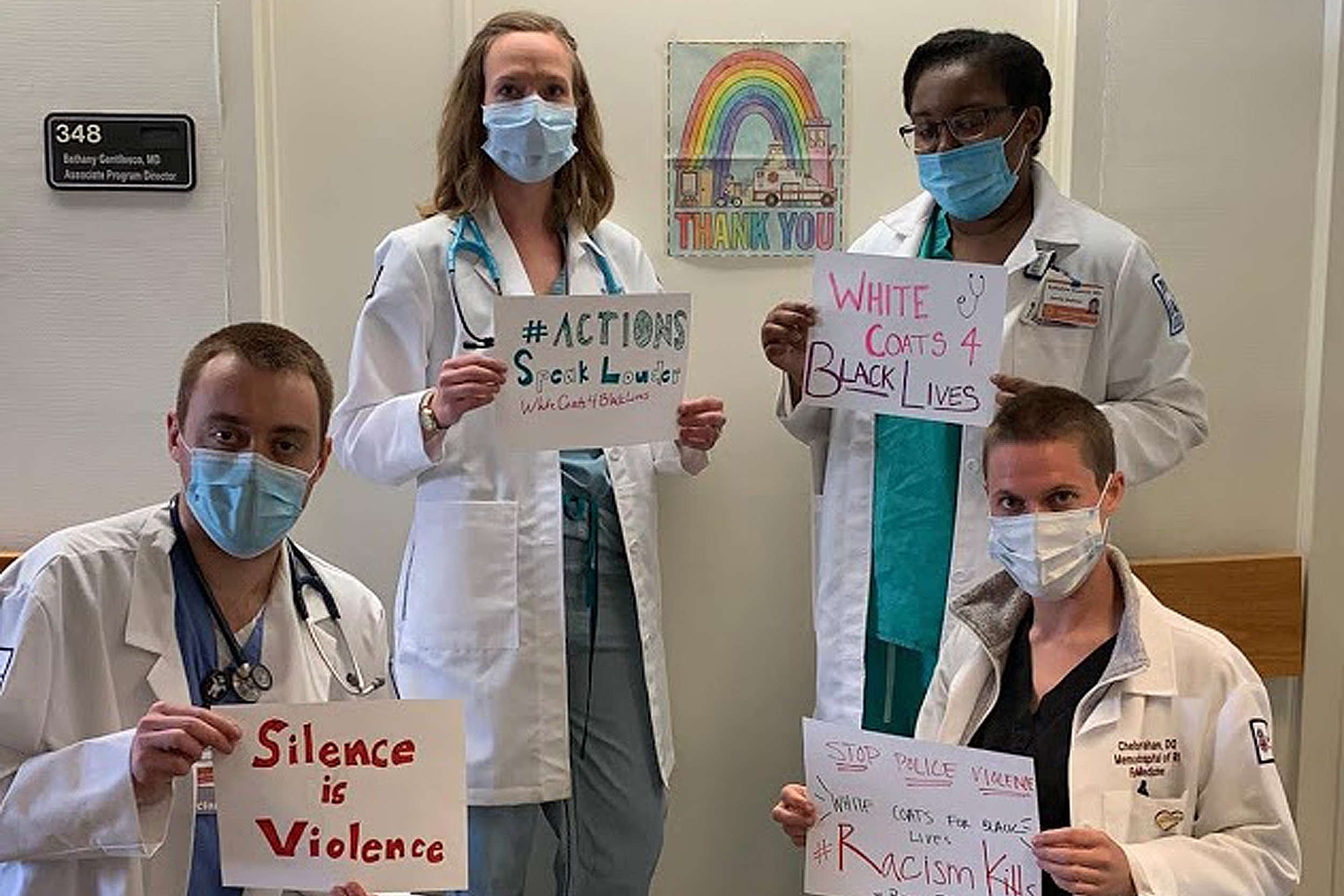

Michelle Morse M.P.H. ’12

Co-founder, EqualHealth and its global Campaign Against Racism

Morse co-founded EqualHealth, which is building a global movement of social medicine educators and practitioners who tackle health inequity, in 2010. The physician and Harvard Medical School assistant professor later co-founded with Camara Jones and others the global Campaign Against Racism (CAR), an initiative that seeks to dismantle structural racism and its effects on health around the world through the work of its 24 chapters in 10 countries. CAR has organized several international conferences and political educational series, created a network of anti-racism groups in Africa, and in partnership with White Coats for Black Lives helped students leading some chapters of the campaign to implement a “racial justice report card” for medical schools and their larger institutions, among other efforts.

GAZETTE: The global Campaign Against Racism is based on the statement “racism inequity kills.” Can you give a few examples of how CAR combats that?

MORSE: First, we know there is a disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the U.S., and we’re leading a working group on how to declare racism a public health crisis as a policy and resource mobilization approach. Second, in the spring our #cancelthedebt social media campaign demanded the end of debt structures from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund that rob Global South countries. We also know that racism leads to inequitable incarceration of BIPOC individuals [Black, Indigenous, and people of color], which is especially well-documented in the U.S., and the resultant unjust rates of COVID in prisons, which will get worse with influenza season. To combat this, we have been doing political education about abolition as a framework that health workers should understand — and get on board with — as a way to fight the prison industrial complex and the appalling health outcomes it creates, from COVID to all chronic disease as well as HIV, hepatitis, and others.

GAZETTE: Was there a project you worked on that illustrates what local action can accomplish?

MORSE: Back in 2018, the Nashville chapter of the campaign decided they were going to organize in order to end the routine practice of race correction in test results of kidney function, which had the result of delaying access to kidney care for Black patients. Eliminating the race modifier has the potential, especially at a hospital that serves a large Black community, to save lives of Black patients with kidney disease earlier. It took two years, but in July Vanderbilt University Medical Center announced that it was going to end that practice. That’s a story of setting out with a very specific goal, holding on to it, and doing what you have to do to get there.

GAZETTE: Tell me about the work you do as part of CAR to educate people.

MORSE: We educate and inform but will also address the miseducation about how racism operates. Health workers have been literally miseducated about not only what causes some people to be sick and others to not be sick, but also about the differences and lack of differences between races and ethnicities. It’s a massive uphill battle because we’re working against existing misinformation and scientific racism.

GAZETTE: What about race and health is often misunderstood?

MORSE: I hear people say, “I understand that race is a social construct, and it was a political invention used to categorize people, but look at the disproportionate maternal mortality rates for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous women compared to white women.” They tell me that there has to be something biological at work that can’t just be explained away by other social and structural factors. Maternal mortality inequities [for women of color] are so stark — and painful, dramatic, and unjust — that folks don’t want to believe that the racial inequities could be fully fixed. We really need to drill down and recognize that, yes, these are serious differences, and they are structurally and socially driven, not from biological differences between people of difference races.

At the same time, we also have to recognize how the experience of racism can cause negative physiological effects, but still this is not a blanket racial biological difference. Scientists, researchers, and social epidemiologist are homing in on that. It’s really about the experience of discrimination. In the coming years, it’s possible we may start to see that those effects can happen for any group that is oppressed. I think research to that effect should be done and needs to come out.

“We often make the mistake of having conversations amongst ourselves, and we don’t even really engage the communities that are most impacted. That has to stop. We can never achieve health equity that way, if we keep talking within our echo chamber.”

GAZETTE: You just completed a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation health policy fellowship in Washington, D.C. What lessons from that experience can you share?

MORSE: I spent the past decade learning and teaching social medicine, and global health and health equity, but I think every person who does health justice work should have an experience like this fellowship. We can’t continue to say how important the social determinants of health are, and then not take the next step and understand our laws, policies, and interests — how they lead to the conditions for health being wonderfully met for some communities and woefully unmet for others. I appreciate the complexity of democracy in this country in a whole new way now. It’s a good thing to be eyes wide open and to better understand my country and its oppressive policy history.

GAZETTE: Was there a moment on the Hill that especially resonated for you personally?

MORSE: I had the opportunity to meet with one of Congressman John Lewis’ staffers several months ago. This was a few months before the congressman passed away. We met in Rep. Lewis’ office, which to me was just like being in a Black history museum. I was able to talk about health policy and health equity in this space, while thinking back to the battles he had to fight. That was a really important moment for me to make that connection between history, the Civil Rights Movement, and the next phase of this battle to find structural solutions for health inequities and liberation.

GAZETTE: Do you have any advice to those who are looking to organize and create in this moment of change?

MORSE: Stick with it. It can sometimes feel like things are going painfully slow, and it’s so easy to want to just give up. I co-wrote a piece for the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Creating Real Change at Academic Medical Centers — How Social Movements Can Be Timely Catalysts” that speaks to this. It describes the misalignment between the mindsets of health workers compared to people who are activists in social movements. Health care training sets us up to make fast decisions, to want fast results, and it makes us think that we’re experts. But it’s important for us to fight that reflex; for example, if the results are not coming fast enough, we want to be able to move on. But we need to recognize that the work of social transformation and organizing is long-term work.

Secondly, for health workers in particular, I think it’s very important for us to follow the lead of community organizers and community-based organizations. We often make the mistake of having conversations amongst ourselves, and we don’t even really engage the communities that are most impacted. That has to stop. We can never achieve health equity that way, if we keep talking within our echo chamber.

Finally, it’s not always helpful to ignore the negative emotions and stress that come with the work. Stop, pause, and hear those emotions, and try not to paint over them with happy feelings and optimism. You can’t do this work without creating that space for mourning and sadness and to have a community where that can all be shared.

GAZETTE: How do you see this moment changing us as a society?

MORSE: The murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others can’t be unseen. The deaths from COVID-19 can’t be ignored. You can’t deny these things. A lot of people have said to me, “I watched that George Floyd video multiple times. I knew I needed to see it.” We can’t run away from it. We have to face it. This will fundamentally shape the worldview of the people who are alive right now, especially this generation that’s mobilizing to fight these injustices. That we can’t unsee these things — that is going to be what shapes the liberatory spaces that we build together. Not turning away helps us to build up those emotional muscles to do this psychologically and emotionally taxing work. That is what takes us into a new future.

Christina Lewis ’02

Founder of All Star Code

A former Wall Street Journal staff writer and author, Lewis started All Star Code in 2013 to focus on preparing Black and Latino young men for careers in computer science, and closing persistent gaps in income and opportunity. Since then, more than 600 high school-aged men of color have completed the All Star Code summer intensive program, its centerpiece curriculum. Many students have gone on to attend top schools and have launched careers at employers like Facebook and Google.

Lewis is an elected director of the Harvard Alumni Association (HAA) and is part of a group of alumni volunteer leaders that has formed to develop new ideas for action against racism, injustice, and inequality, in partnership with HAA. She also is a member of the Dean’s Advisory Cabinet at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

GAZETTE: What drew you to helping young men of color and, in particular, the technology industry?

LEWIS: Tech is the engine of our civilization today. Not only are tech jobs supposedly the ticket into the middle class or even the upper class, but tech and software are driving everything. They say that even if engineers aren’t running civilization, they build the software that runs civilization. The people who are building these products are incredibly influential. But there are far too few Black and Latinx people in tech. Only 1 or perhaps 2 percent of engineers at major companies are Black, and the numbers are similar for Latinx people.

Eight years ago, I saw these wonderful programs starting up for girls, holistic programs with mentorship opportunities, focused on all different ages. When I looked at what was available for Black and Latino boys, there was virtually nothing. What was available were things like broadband access, free computers — tools that weren’t part of holistic approach. There are about 3 million Black and Latino boys in the United States, and this group faces huge challenges that are distinct from other groups. We need everyone to be on the playing field.

GAZETTE: Let’s talk about your summer intensive course. What do the students take back to their schools, to their lives?

LEWIS: Students apply as sophomores and juniors for this six-week course. They return to their school having learned to code, to build websites, and to understand how to navigate the tech field. The capstone project has them, as a group, build a web app or even a mobile app. They then demo that to an audience of their peers. This is the classic way that engineers operate. Many of our students have gone on to start nonprofits. This is all in high school. A few are creating programs to teach other students in their community.

GAZETTE: Can you share the story one of the students who has gone through the program, how it has helped him?

LEWIS: I think of one young man I met who was really into wrestling, had lots of drive. He was in a good school focused on empowering Black boys, but he was not a high performer academically. And he had many friends who entered the criminal justice system during his freshman and sophomore years, and I remember he said to me, “I don’t think I want my life to go that way.”

He did our summer intensive after his junior year, and he had that spirit of wanting something better for himself. He took to coding like he’d taken to wrestling. He was one of our first students, in a cohort of only 20 boys. It really motivated him to see other Black boys his age and from all different income backgrounds — but all with dedication and drive. He went back to school and outperformed expectations in a major way. He ended up going to a great school and majored in computer science. He beat these horrible statistics about how low-income, under-represented Black and Latino boys perform in college. His life trajectory was changed. He’s now working as a software engineer at a large startup in a job that is pandemic-proof. And he’s already thinking about giving back: He wants to create a job listing app for people in the criminal justice system.

GAZETTE: Of course, the work supporting these students doesn’t end in the classroom. How does All Star Code address that?

LEWIS: This current movement about racial justice has shown us this that racism doesn’t end when you have a job. We know this. A student like the one we talked about is often presented as a success story, and the narrative can be that now that he has a job, he’s fine. Yes, he has certainly beaten the odds, worked hard, done well, but the challenges Black people face don’t end when you graduate college, and it doesn’t end even when you become wealthy. Systemic racism permeates the entire society.

This is where our community model makes sense — the idea of mentorship, keeping those connections to peers. An increased sense of belonging is proven to help someone persist when things are difficult, and the way you have an increased sense of belonging is being around people you identify with, working together.

“This current movement about racial justice has shown us this that racism doesn’t end when you have a job. We know this. … Systemic racism permeates the entire society.”

GAZETTE: Just a few weeks ago, you launched a new nonprofit called Give Black. As with All Star Code, was this a way to address an unmet need?

LEWIS: It was a response to the murder of George Floyd, the outpouring of support for Black lives. Seeing such a willingness to pour real money, time, and attention into Black causes serving Black people, I realized there was no easy way to find organizations to support. So, we created a website and movement to foster increased giving to Black nonprofit organizations. The website is a comprehensive database of Black nonprofits sorted by category so as to connect donors to Black organizations and causes that they care about. We have 250 organizations already and counting.

As we’re fostering increased attention to these organizations and lifting up the whole sector, we’re creating a series of knock-on effects. When you’re growing these Black organizations, you’re empowering Black leaders, which is crucial. These organizations are also more likely to employ Black people, so you’re creating jobs and adding to the economy. Your money is helping to solve problems, but it’s also being used to activate the people who are likely to be the most effective because they’re closest to the problems.

GAZETTE: In this moment of racial awareness, what kind of impact do you hope All Star Code can have?

LEWIS: In terms of equity, it’s clear now that Black and Latino boys are have not received their share of support and resources. The dropout rate for Black boys in the education system is devastating. Technology has to be a part of changing and rebuilding institutions to make them inclusive and anti-racist, and All-Star Code is part of this fight against systemic racism by helping build leaders who will know how to create the tools and products to solve problems.

I feel very optimistic about what this younger generation can do. These young people, including our students, are very forceful in advocating for what they believe, and they are working hard to push us older people to be more innovative, too. In 2002, when I graduated, we said “We’re not going to be cogs in the finance or consulting wheel,” but we were still cogs, just in a different wheel. This generation is assessing how things are, and deciding how they can be different. They inspire me.

Stephen Milliken ’73

Founder and CEO of JusticeAid

Following a career as a judge for more than 20 years, Milliken founded JusticeAid in 2013 to use music and the arts to raise money for other nonprofit civil rights organizations. By working with acts like Blind Boys of Alabama, Ani DiFranco, and Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue, they have organized performances that have raised more than a million dollars for groups like Gideon’s Promise, Civil Rights Corps, Innocence Project New Orleans, and the Immigrant Defense Project. JusticeAid also hosts public forums and launched a social media campaign that encourages public engagement with issues of social justice. Their “Songs of Protest: 12 Months of Music that Matters” project has released a playlist of protest songs with a different focus each month this year.

In May, JusticeAid hosted an online benefit to support the Election Protection 866-OUR-VOTE campaign of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the nation’s largest nonpartisan voter protection coalition, and they hosted another concert to support the group this month, with artists Rosanne Cash, Ivan Neville, Tom Morello, Lila Downs, and Regina Carter.

In addition to serving as a judge in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, for more than 20 years Milliken taught in Harvard Law School’s Trial Advocacy Workshop.

GAZETTE: How has your work as a judge shaped your desire to fight for social and racial justice?

MILLIKEN: As somebody once said, if there is a fight between two white students in a well-funded school, it becomes a matter for the principal and maybe their parents. If it’s two black children, in an underfunded school, where police are present, it can be a different story, one that ends with an arrest record and jail. I look back on 22 years on the bench, years of walking into the courtroom where the juveniles being prosecuted were disproportionately African American, and significantly so. I saw enough of that. That’s why I’m doing this work now.

GAZETTE: How did JusticeAid come to be?

MILLIKEN: It happened over conversations with some colleagues who were teaching at Harvard Law School’s trial advocacy workshop. A couple of us, former public defenders, talked about our frustration with the criminal system and how we might use the arts to create change, because we all cared about civil rights and loved music. That led to a dinner, more conversation, and we, the dinner guests, became the founding board.

At first, we thought, let’s just rent a hall, hire a couple of musicians to play a benefit show, and invite our friends and family. After that concert, somebody came up to me and said, “When are you going to do the next show?” On another occasion early on in our existence, a concert at the City Winery in New York City for the Mental Health Project of the Urban Justice Center, somebody asked me, “How many of these shows do you do a month?” I burst out laughing, because we’re a little volunteer organization, and we could only do a couple of concerts a year. The appetite for concerts and our public conversations has only grown from there. It’s enabled us to connect with the most powerful civil rights activists and get money in their hands.

GAZETTE: What does the impact of this work look like?

MILLIKEN: For our first show, we raised $40,000 for Gideon’s Promise, which was formerly the Southern Public Defender Training Center in Atlanta [a group of public defenders who provide equal justice for marginalized communities]. It made a profound difference in helping that organization to thrive, and they have flourished since. Now they’re doing trainings all over.

Our concert with Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue supported Justice for Vets, which is a diversion program under the National Drug Court movement. The money we raised from that concert went to hiring a marine and paying for his work to go all over the country to support and help develop veterans’ treatment courts, which found alternatives to incarceration for thousands of veterans.

GAZETTE: What lies at the heart of the change you want to create?

MILLIKEN: A lot of our work has had to do with access to justice and with a particular focus on racism and mass incarceration, as the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. There is a devaluation of people of color that leads to this inhumane treatment and human caging. So, we’ve really tried to draw a bead on identifying the criminalization of poverty and of disenfranchised people, particularly of color, and disproportionately focused on Black men.

In many ways, historically, America has never met a problem it couldn’t lock up. Frequently the knee-jerk reaction is to defund mental health and other services, expand law enforcement — really to just call the police. We lock up children, people with mental health challenges. We lock up the homeless. DNA evidence evens proves how often we lock up the innocent. We make poor people pay for unconstitutional money bail, fees, fines, and all manner of services, and then when they are unable to make those payments, a warrant is issued, and they get arrested and prosecuted for things like contempt or a technical violation of parole or probation. And when you think of the people who have tragically encountered police in minor situations, like Eric Garner selling cigarettes on the street, and ended up dead — it’s a human tragedy of horrific proportions.

GAZETTE: What’s it like to be at a JusticeAid concert?

MILLIKEN: Our concerts are proof of the power music can have when it combines with the movement for reform of the criminal system. I think we knew that intuitively, and that’s what drew us to create JusticeAid, to draw on that power.

I remember our concert featuring Dr. Michael White, a great bandleader out of New Orleans, a clarinetist, and the Original Liberty Jazz Band. At the end of his set, there was just this spontaneous response — out come the handkerchiefs and table napkins, and a spontaneous second line formed, New Orleans style, and it just snaked through the club.

Then there was the concert we did to support the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project and the Innocence Project New Orleans. We had people who had been exonerated and freed from prison in the audience, and at the intermission they came forward to speak. All of these people had been in prison for crimes they didn’t commit, including one man who had been wrongfully imprisoned for more than 30 years. In fact, he and the complainant appeared together at a JusticeAid forum to speak to the police abuses that lead to the wrongful conviction. I remember, his concern was all for her suffering, and not his imprisonment. That degree of magnanimity was the essence of story after story of these individuals who had been freed by the work of the Innocence Project offices. There were people in the audience who had no idea that this was happening. Later, the Blind Boys of Alabama, one of the acts, came down off the stage and led a parade through the theater. There were probably 700 people stomping and marching, and in the middle of that performance there was a spontaneous request for funding, and people opened their wallets and pledged $14,000 just right there on the spot in the theater. That event raised more than $100,000. That swell from the audience of people wanting to give, I’m sure that comes from the inspiration of the evening, at least in part. We believe in that.

“This movement has become so diverse, so broad, so deep, and so constant, that it has allowed us to really tear the cover off the ball and have a look at who we really are, and what we need to do to become a just society.”

GAZETTE: How do you select the nonprofits you choose to partner with?

MILLIKEN: We started out by aiming to find organizations at tipping-point stages, where our support would make an enormous difference.

With the Innocence Project, for example, we did some research and learned that the Innocence Project New York has a great deal of money; it’s a very worthy organization. But there were lots of regional and local Innocence Project offices around the country, none of which are funded from that national New York lead office. I don’t think people realize that there is a shocking underfunding of social justice nonprofits, particularly criminal justice civil rights organizations.

GAZETTE: What is your hope for the direction of the racial justice movement?

MILLIKEN: This movement has become so diverse, so broad, so deep, and so constant, that it has allowed us to really tear the cover off the ball and have a look at who we really are, and what we need to do to become a just society. I think we need to continue to push for understanding and connection, for a real examination of white supremacy and privilege, to ask people to get connected and to “do uncomfortable things,” as [founder of the Equal Justice Initiative] Bryan Stevenson [M.P.P./J.D. ’85] says, and to ask what they’re willing to sacrifice for justice.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.