A divine cosmos

Library research fellowship helps a junior develop a new visual methodology

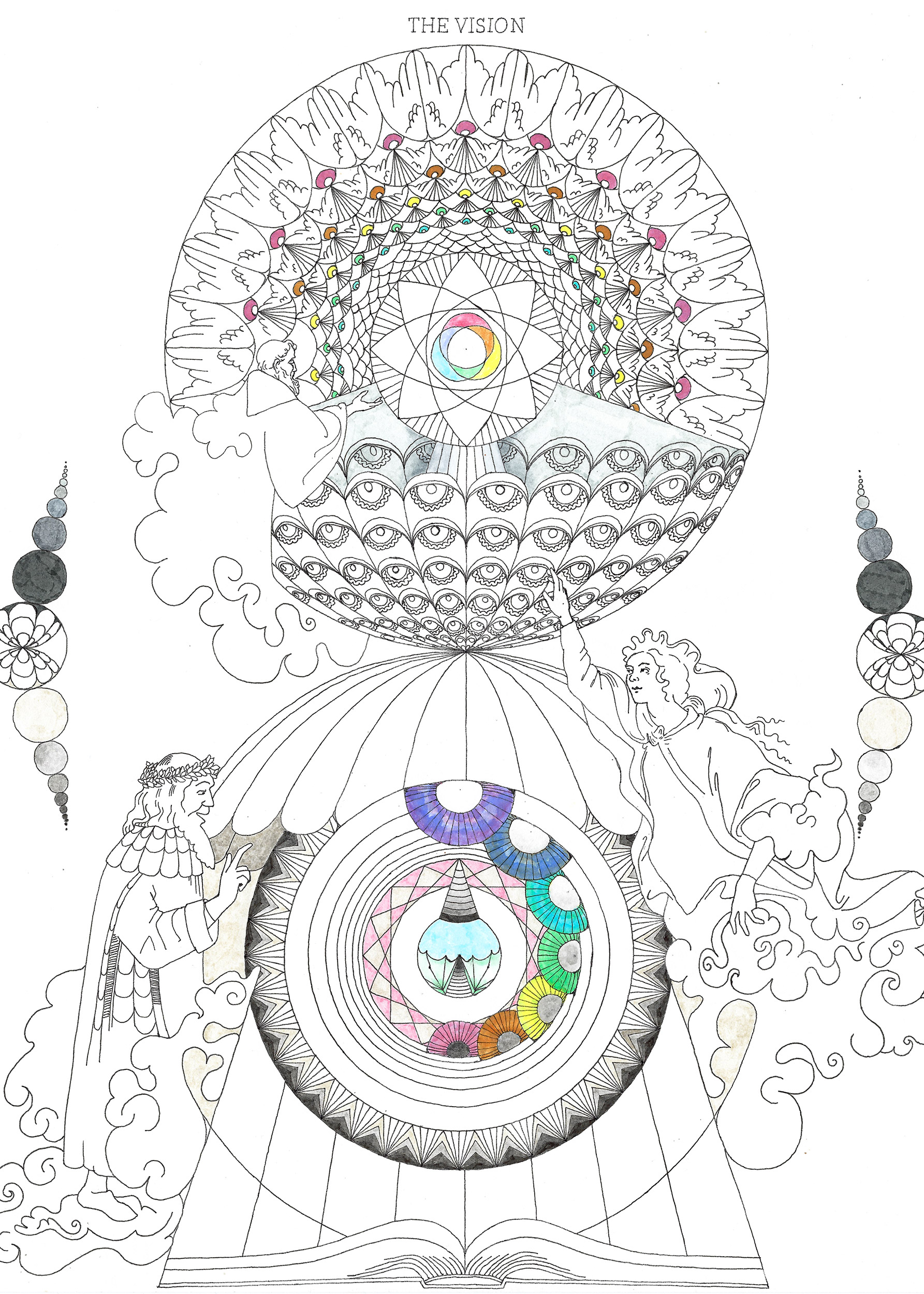

A hand-drawn cosmographical map of Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy,” created by Madeleine Klebanoff-O’Brien ’22 through her summer fellowship at Houghton Library.

Courtesy of Madeleine Klebanoff-O’Brien

As she ended the academic year last spring, Madeleine Klebanoff-O’Brien ’22 was hoping that unlike so much else, her summer research fellowship at Houghton Library wouldn’t be canceled due to the pandemic.

Luckily for her, the library was ready to take the fellowship virtual — and two months later, she has not only gained a new set of research skills, she’s developed a new way of looking at research altogether.

Klebanoff-O’Brien, whose research focused on Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy,” concluded her fellowship by creating a fully image-based research product. She illustrated Dante’s entire cosmos with visual details pulled from Houghton sources, including depictions of Earth’s elements inspired by medieval astronomical texts and drawings of angels based on 14th-century woodcuts. To explain the map’s symbolic elements to an average viewer, Klebanoff-O’Brien also made an image-based commentary.

“My revelation in this work has been all the associations that can be built visually,” she said. “The idea that the eye can make an association before the mind can.”

Image gallery

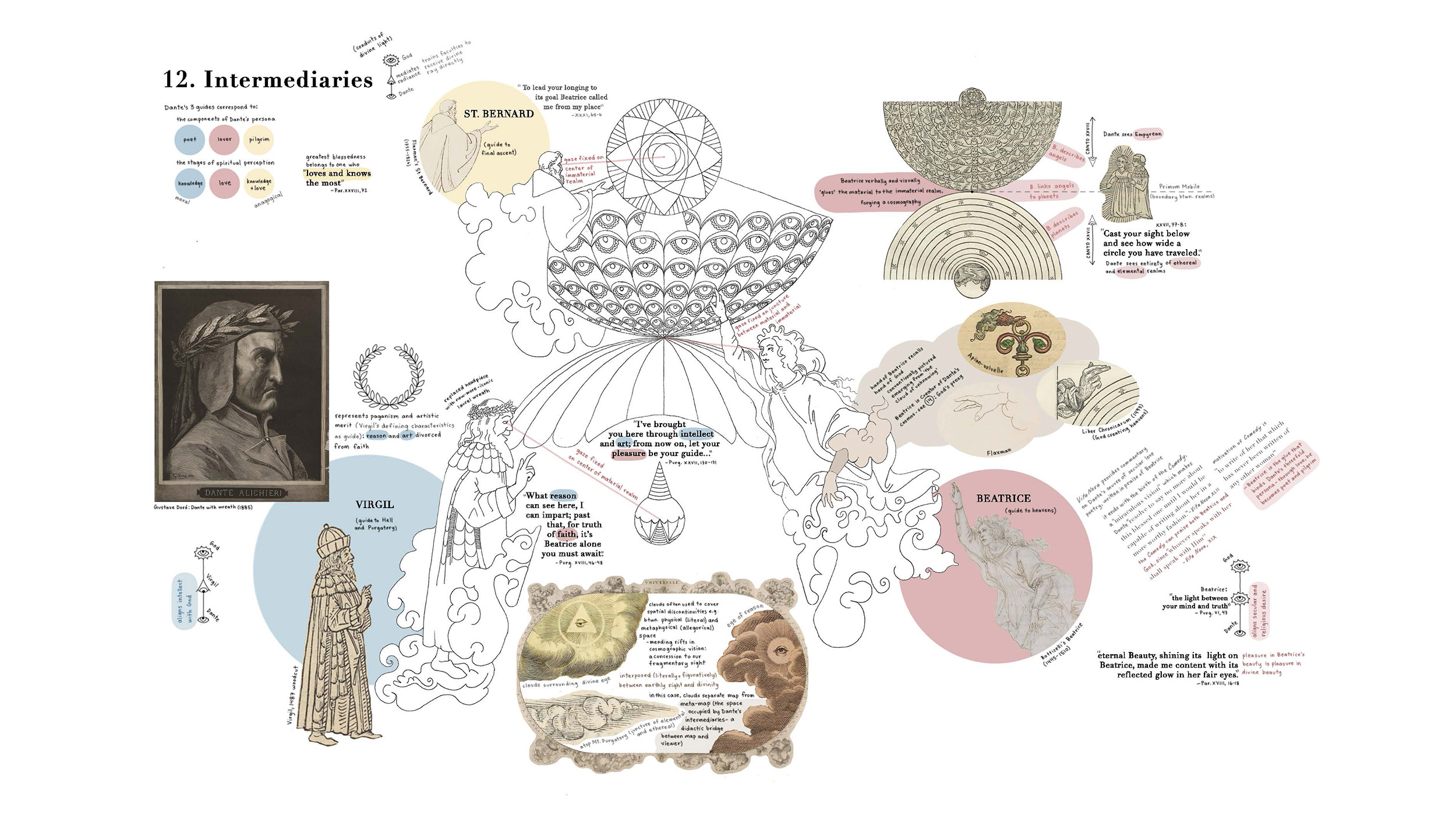

A page of commentary shows the artistic inspiration for Klebanoff-O’Brien’s depictions of Dante’s three guides: Beatrice, Virgil, and St. Bernard.

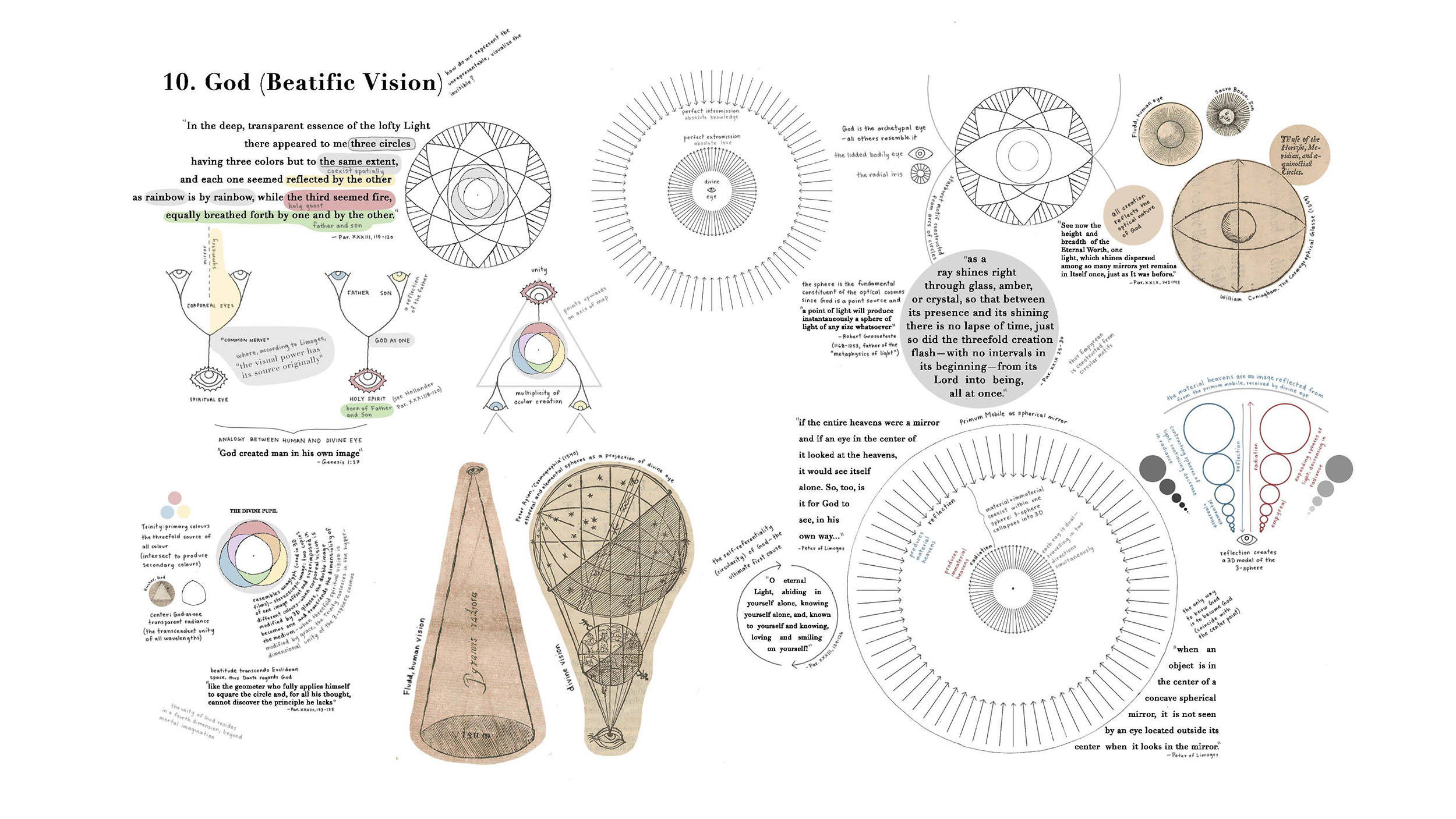

Klebanoff-O’Brien’s inspiration for illustrating the eye of God in her map of Dante’s cosmos.

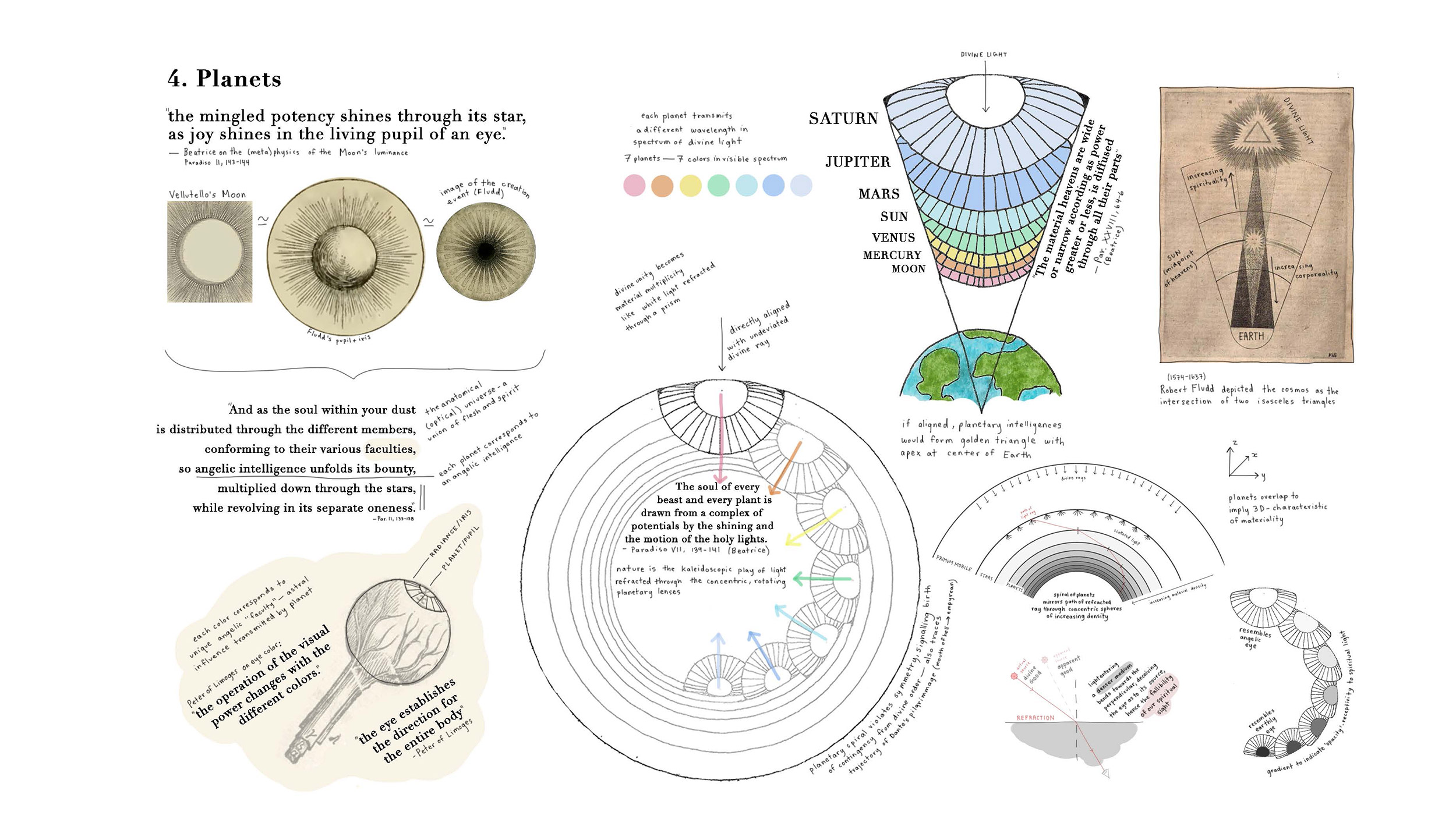

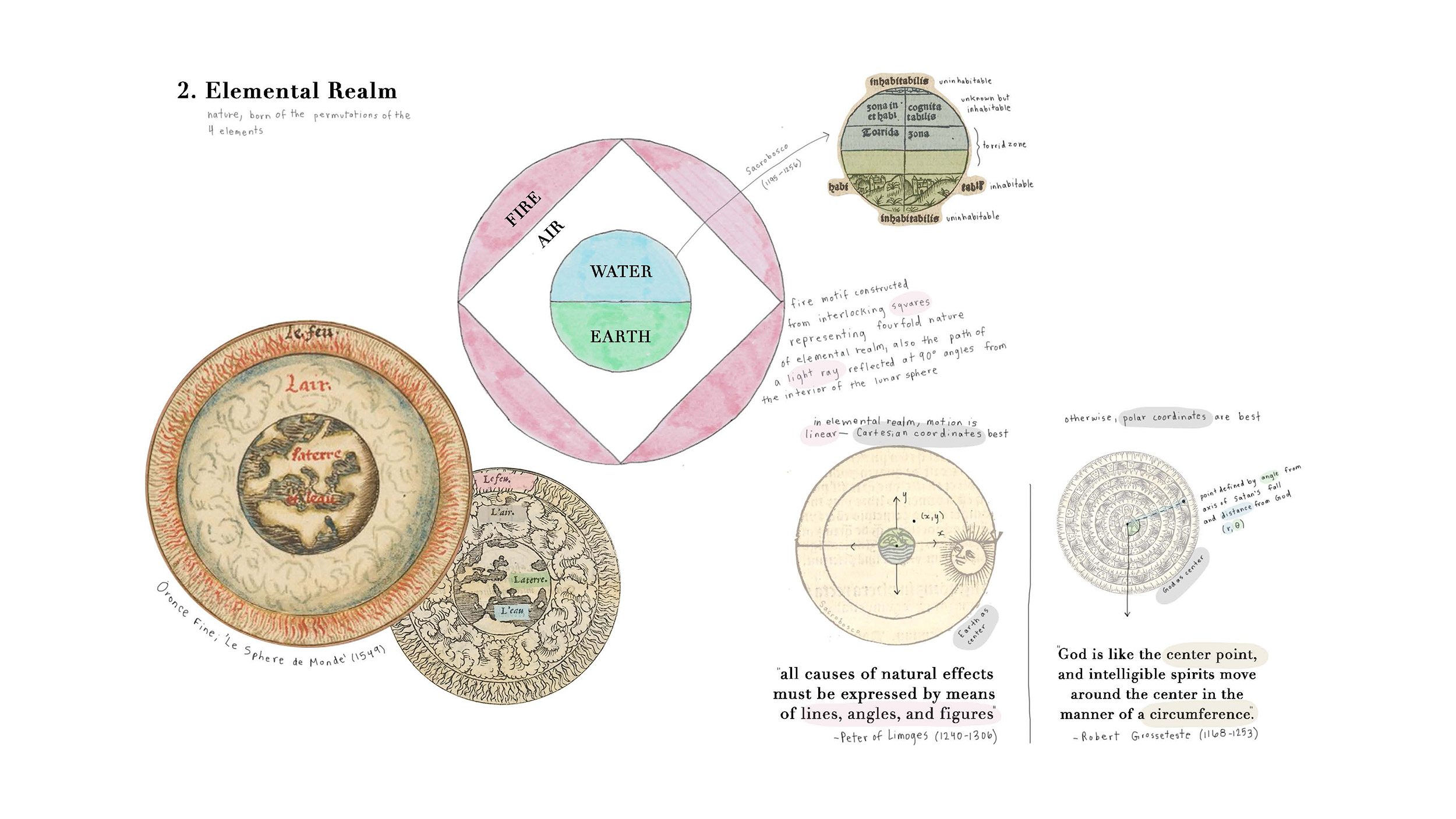

A page of commentary shows how Klebanoff-O’Brien chose to illustrate the planets in her cosmographical map, drawing from the text of the ‘Divine Comedy’ as well as work by English scientist and philosopher Robert Fludd and by theologian Peter of Limoges.

Klebanoff-O’Brien’s cosmographical map, showing her illustration of Earth’s elements based on Dante’s text and other sources.

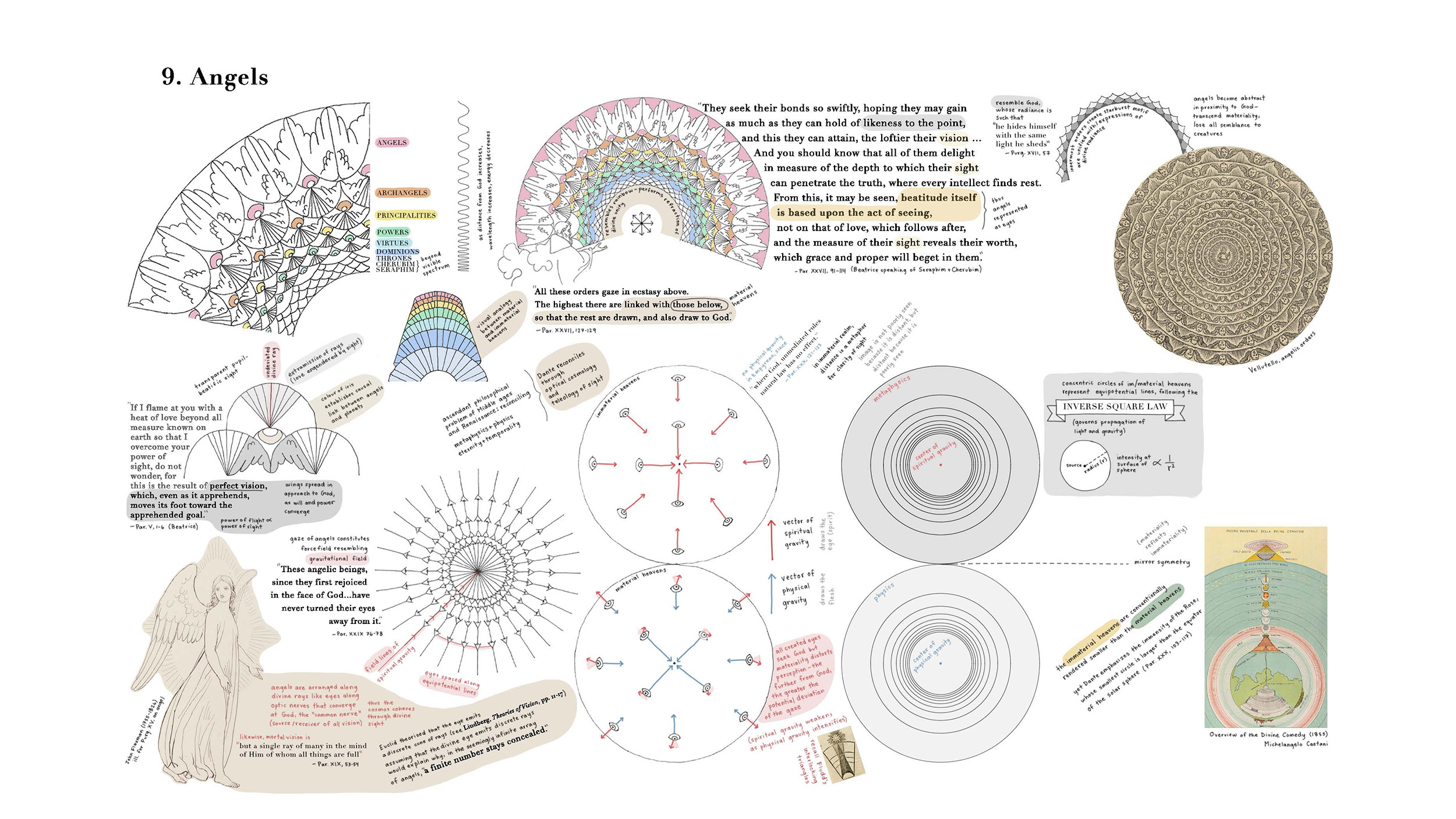

Angels in Klebanoff-O’Brien’s cosmographical map, inspired by mathematical ratios, the visible light spectrum, and a 14th-century woodcut from an edition of the “Divine Comedy” published by Alessandro Vellutello.

Klebanoff-O’Brien, who is a comparative literature concentrator, had never done independent research before her Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program (SHARP) fellowship at Houghton, a collaboration with Harvard’s Office of Undergraduate Research. The fellowship, which supports building research skills, showed her that both conducting and presenting research can allow for creativity.

“It’s been very freeing to approach things this way, through this visual lens,” she said. “I want to do more in the future, bringing that visual methodology into studying texts.”

Her cosmographical map represents hell, purgatory, and heaven as described in “The Divine Comedy,” and shows how the three are interconnected using symbols and images from the materials in Houghton. Klebanoff-O’Brien incorporated drawings of Dante’s three guides into the map, as well — her depiction of Beatrice is inspired by a Botticelli drawing, while her Virgil is based on an early woodcut, and St. Bernard on a more contemporary illustration.

Creating a cosmographical map, she said, allowed her to explore how illustrations of “The Divine Comedy” can add to the reader’s experience, while letting her participate in this tradition rather than just study it.

“The cosmographer tries to forge a [visual] link between the three realms … and synthesize everything into a total vision,” she said. “The idea is, by allowing the [reader] to see with this total vision, the reader can experience a shadow of Dante’s own enlightenment.”

“It’s been very freeing to approach things this way, through this visual lens.”

Madeleine Klebanoff-O’Brien ’22

Houghton Library’s head of teaching and learning, Kristine Greive, who managed Klebanoff-O’Brien’s fellowship, said, “Part of learning to do an intensive research project like this is learning where you have something to add.”

In Klebanoff-O’Brien’s case, depicting all three of Dante’s realms in a single image is novel, while her image-based project commentary is “unique and fascinating,” Greive said. “She’s done some really interesting work.”

The Office of Undergraduate Research offers 10 to 15 SHARP fellowships annually, Greive said, but Houghton’s is the only one that gives student applicants full license to choose their project rather than asking for assistance with an existing project.

When Klebanoff-O’Brien applied for the fellowship, it was with the idea that she would focus on Dante illustrations. Since high school, she has viewed Dante’s works as a fascinating intersection of literature, art, and science.

“I knew I wanted to explore Dante more, especially the visual angle,” she said.

Houghton has a vast, digitized collection of woodcut illustrations of “The Divine Comedy” from the 1400s, which Klebanoff-O’Brien anticipated using for her project. But many of the other sources she ultimately used to create her map — including pre-Copernican astronomical materials, Renaissance-era manuscripts, and Bible illustrations — were unexpected.

“She kept looking beyond the bounds of what she thought she was looking for,” Greive said. “I think it’s a [lesson that] being curious and playful and casting a wide net can be informative and transformative to your research.”

“The fellowship is an opportunity for undergraduates to follow their own passion and explore something that comes entirely from their own interest, as long as it’s supported by our collections.”

Kristine Greive, Houghton Library

Greive said she strongly encourages future applicants to the SHARP fellowship to think about creative research projects like Klebanoff-O’Brien’s.

“The fellowship is an opportunity for undergraduates to follow their own passion and explore something that comes entirely from their own interest, as long as it’s supported by our collections,” Greive said. “We’re excited to see any research project, no matter what form it takes.”

Though this year’s research project was unexpectedly virtual, both Greive and Klebanoff-O’Brien were grateful the SHARP fellowships were able to take place remotely.

“Of course, it was sad not to be able to see these incredible resources at Houghton in person, but I did feel I was still able to create something I was excited about,” said Klebanoff-O’Brien. “It turned out really well. It was the perfect companion during the pandemic.”

For Greive, the success of the virtual fellowship has shown her what Houghton can do for students even when the library building is closed.

“Working on this fellowship has been such an uplifting experience,” she said. “It’s helped me see how much meaningful teaching and learning can happen with special collections over Zoom.”