Viewing flattened fossils in a new light

Artist rendering what the shrimp-like Cambrian species may have looked like.

Illustration by Xiaodong Wang

Micro-CT lets scientists see telling 3D details in arthropod evolution

The shrimp-like fossil was discovered in the 1980s, and researchers knew almost nothing about it other than its species. It turned out even that was wrong, but the big story here isn’t as much the end as the means.

After a team of paleontologists, co-led by a Harvard scientist, used special X-ray imaging in 2018 to create a 3D rendering of the ancient specimen, they discovered the fossil was a completely unknown species that had lived sometime in the early Cambrian, approximately 518 million years ago. The creature they described was particularly fierce. Though only 2 centimeters long, it brandished 810 dagger-like spines that were divided among its 54 legs. It used them to shred prey, like worms, on the ocean floor.

The discovery was published this summer in BMC Evolutionary Biology and is one of the latest examples of a growing body of research opening new avenues in how scientists understand the early evolution of arthropods, all of it made possible by the use of the imaging technique called micro-computed tomography, or micro-CT.

The work is partially funded by the Harvard China Fund and has led to five papers in the past year and a half that have helped reveal new details of early Cambrian fossils. The features formerly had been undiscernible through more conventional methods; taken together, they are helping cast further light on why we have the species of spiders, crabs, butterflies, and other arthropods we do today.

“Usually, we can only see one side of the animal [because of the way these fossils are stuck on the rock on which they are preserved],” said Javier Ortega-Hernández, an assistant professor in the Harvard Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and curator of invertebrate paleontology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. “But, ideally, we want to get to the underside, which has all the juicy, lovely details.”

That is what Ortega-Hernández has been doing during the last five years in conjunction with Yu Liu, a paleobiology professor at Yunnan University in China, using micro-CT.

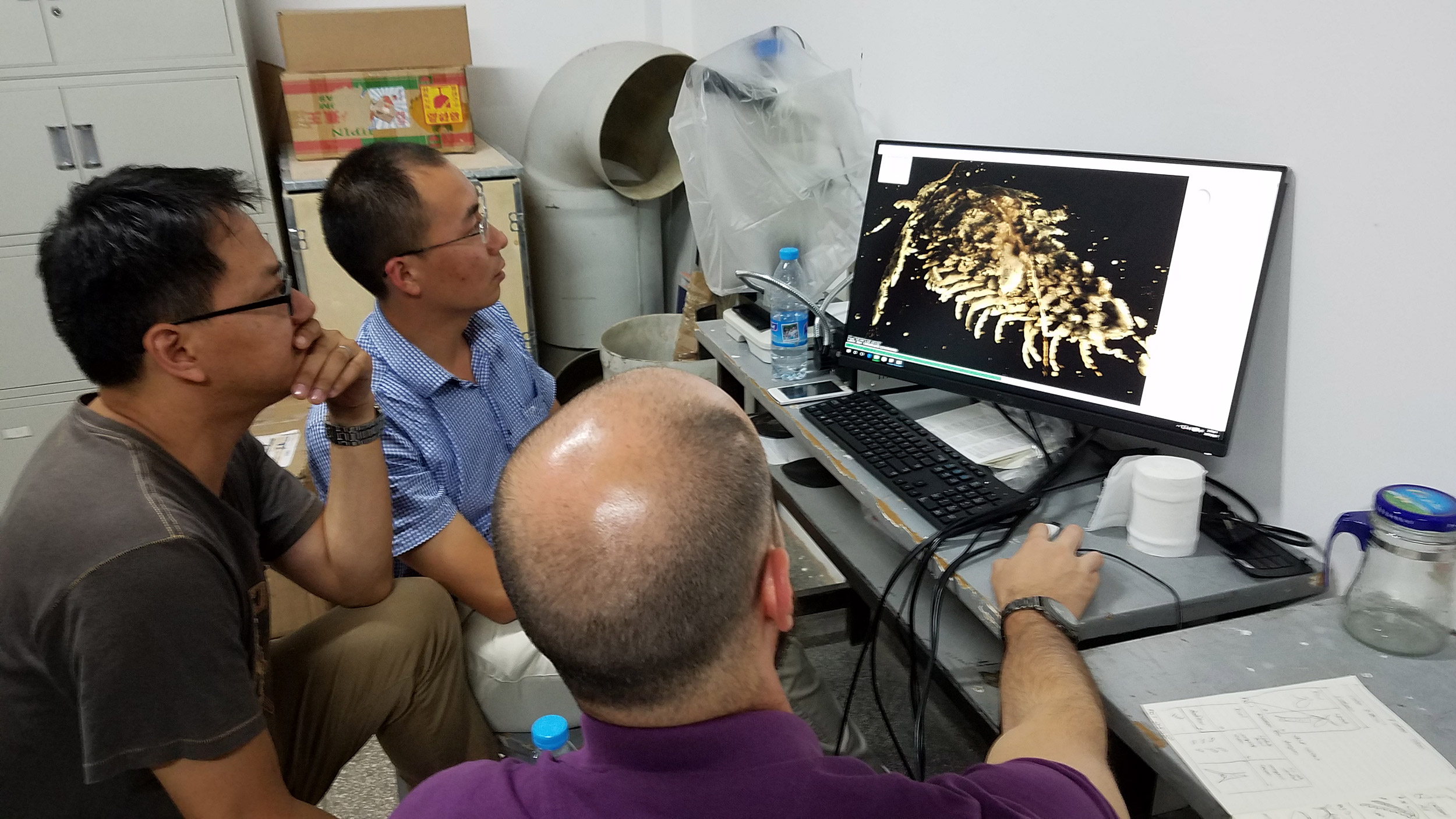

Joanna M. Wolfe, studying the part and counterpart of the Ercaicunia fossil on a microscope. Researchers Dayou Zhai (from left), Yu Liu, and Javier Ortega-Hernández, looking at the 3D model of Ercaicunia.

Photos by Dayou Zhai and Joanna M. Wolfe

The method is basically a creative way of getting around the common problem with almost all Cambrian arthropod specimens: While these macrofossils are big enough to see without a microscope, they often resemble a piece of flattened roadkill and are fused with the slab of rock in which they are found. It often makes it almost impossible to put together an accurate picture of the preserved animal with all its features and traits.

The technique works a lot like the basic X-ray a person gets for a broken arm. The main difference is this machine is a lot stronger, since instead of soft tissue, the researchers are using it to look through chunks of rock, iron, and minerals like pyrite. The fossils are placed on a rotating stage and then the X-ray machine takes thousands of digital photographs as it slowly completes its cycle. Those images are then compiled to make an interactive 3D rendering of the animal the researchers are studying.

The process has been gaining prominence in the study of Cambrian arthropod macrofossils during the past five years, as micro-CT machines have become more powerful, affordable, and common in research labs around the world.

“It is a very exciting way of being able to study again some of these animals that we either thought we knew and [now] we’re finding new details on, or, alternatively, that we knew very little about because sometimes they’re just so poorly preserved,” Ortega-Hernández said. “With this approach, even a single crummy specimen has the potential of revealing amazingly well-preserved features in 3D … that can transform everything.”

It’s this technique that Ortega-Hernández and Liu used to discover the unique features on that knife-wielding, shrimp-like creature they dubbed Xiaocaris luoi. Using the scan, they were able to discern other tantalizing details. For instance, the creature is a distant forerunner of some of today’s arthropods, like spiders, centipedes, and, of course, shrimp. It had a hard exoskeleton to protect itself from predators, a boomerang-shaped head, a pair of antennae it used to sense its environment, and it moved in a wave-like motion similar to a sea monkey.

In another paper published in June in Current Biology (just weeks apart from the paper on X. luoi), the scientists looked at the head morphology of another problematic group of early Cambrian arthropods called megacheirans, specifically, a sample of the species Leanchoilia illecebrosa. Using micro-CT, they were able to show its head organization with unprecedented detail, including a precise location of the eyes, claw-like appendages, and the unexpected presence of a flap-like labrum near the mouth.

Using micro-CT, the researchers were able to show the head organization of the species Leanchoilia illecebrosa with unprecedented detail, including a precise location of the eyes, claw-like appendages, and the unexpected presence of a flap-like labrum near the mouth.

Video courtesy of Javier Ortega-Hernandez (Invert Paleo Lab) and Chen et al. 2019 (BMC Evolutionary Biology)

This discovery was important because the flappy labrum, a kind of upper lip, lies in front of the mouth of most arthropods living today. The finding supports the theory that Leanchoilia and other megacheirans are distant relatives of the living group of arthropods known as chelicerates. They include modern horseshoe crabs, scorpions, and spiders. Until now, the existence of a labrum in megacheirans and its position have been the source of heated debate in the field. It is considered one of the most important features of an arthropod’s head and has prompted very different interpretations about their evolution.

The group published three other papers as part of this work. Two of them were also in Current Biology and BMC Evolutionary Biology, while another was in Geological Magazine.

In the other Current Biology paper in 2019, for instance, the team looked at the Cambrian ancestor of crustaceans to describe the antennae and mandibles on its head in greater detail than previously had been possible.

“Having the additional data that come from the scans, it basically lets you see that much more,” said Joanna M. Wolfe, a research associate in the Ortega-Hernández lab and co-author of that 2019 paper and another. “You can make a more direct comparison of the fossil onto its living relatives.”

The samples the group works with each came from an area in the Yunnan Province in China called the Chengjiang Biota. It’s a popular spot for paleontologists because it’s bustling with diverse and well-preserved Cambrian fossils.

Liu and Ortega-Hernández first connected in 2015 on another project, and have been working together on this one ever since Liu sent Ortega-Hernández micro-CT scans of an ancient fossil.

“With this approach, even a single crummy specimen has the potential of revealing amazingly well-preserved features in 3D … that can transform everything.”

Javier Ortega-Hernández

“I had no idea what I was looking at, but it looked really nice,” Ortega-Hernández said. “It just became a very organic collaboration in that we would have this back and forth between us to refine the interpretation, discuss the broader significance of the discoveries, and simply engage in a very active collaborative effort altogether.”

Most of the scanning work is done in China at Yunnan University, largely to avoid damaging the specimens in travel. It means a lot of the work happens remotely, but Ortega-Hernández and members of his lab are no strangers to visiting Liu’s lab in China to do some analysis. In fact, it goes both ways. Liu has been working at Harvard for the past year as a visiting researcher. He even brought some specimens with him.

“Before COVID-19, we had several face-to-face discussions which were so stimulating and led to some very good ideas as to how some of the scientific problems should be addressed or might be solved,” Liu said. “Our recent Current Biology paper, for instance, was not in the original plan of my visit. It came out naturally after those stimulating discussions.”

Still, the ability to access the data remotely comes in handy, especially in the classroom.

“I would love to be able to showcase fossils from China in my classroom,” Ortega-Hernández said. “But that is not simply not possible … but what I can do is show them amazing 3D models, which are visually stunning and actually have even more data than the fossil itself.”

Ortega-Hernández and Liu say the research isn’t stopping anytime soon.

“We have only really begun to scratch the surface because there are hundreds of species and thousands of specimens in this deposit and we have only used this approach with about a dozen or so,” Ortega-Hernández said, referring to the Chengjiang Biota. “There is a lot of work still to be done.”

Javier Ortega-Hernández will speak about his work in a free virtual Evolution Matters Lecture on Wednesday, October 14 at 6 p.m. sponsored by the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture.