Video by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

‘Moving in the right direction’

Harvard science labs begin to reopen

Close to 2,000 faculty and staff from the FAS Division of Science and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) returned to their labs after nearly three months this week, marking a new phase in a gradual effort to resume scientific research in everything from the laws of physics and quantum science to using gene regulation to find therapeutics for cancers like leukemia.

The reopening from the COVID-19 scale-down started June 8.

“It’s brought a lot of optimism,” said Conor Walsh, the Paul A. Maeder Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences and principal investigator at the Harvard Biodesign Lab. “People feel good that we’ve put together conservative plans that have allowed them to limit interactions, limit the risk of transmission of COVID-19, and get back into their work. Even if it’s not going back to normal, that still brings a lot of positivity.”

Walsh, who’s also a core faculty member at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and a member of the University’s Laboratory Reopening Planning Committee, felt that optimism himself when he walked through the fourth-floor lab on Oxford Street as a few researchers marked off walkways and work spaces with tape and posted room-occupancy limits to help enforce social distancing guidelines and meet safety measures set by the University. Everyone wore a Harvard-issued mask.

“Everyone wants to show that we can do this safely and set a good example for others to follow,” Walsh said.

Neuroscientist Catherine Dulac feels the same way. In her lab on Divinity Avenue, the moment was met with excitement as her researchers picked up their work studying social behaviors in the brain.

Conor Walsh and Catherine Dulac.

File photos by Rose Lincoln and Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff

“We are all elated,” said the FAS Higgins Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and the Lee and Ezpeleta Professor of Arts and Sciences. “We’ve been very antsy over the last few weeks, in particular, because it was clear we were going to go back quite soon. … We had plenty of time to think about what we were going to do now that we could back so it’s a very polished list of experiments.”

Postdoctoral fellow Fabiana Duarte, who researches gene regulation in the Buenrostro Lab, spent her first day back getting through her own to-do list.

From 5 p.m. to 10 p.m., the evening shift, Duarte took inventory of what reagents she had, ordered new ones, and started thawing some of her cell lines so they could be cultured and analyzed. As the lab’s safety officer, she also spent some of the day making sure everyone was following the new protocols. They take some getting used to and detract from the typical level of collaboration in the lab, but it’s absolutely necessary, Duarte said. She is happy to be back

“When we were shutting it down, we didn’t really know what was going to happen. It was very uncertain times,” Duarte said. “Now — and I can’t speak for everybody but for me and the people that I’ve been talking to — it feels good because even though it is very limited and we’re not back to normal, you do get that sense that we are moving in the right direction.”

“Everyone wants to show that we can do this safely and set a good example for others to follow.”

Conor Walsh, the Paul A. Maeder Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences and principal investigator at the Harvard Biodesign Lab

Getting to this point involved around-the-clock logistical magic across FAS and SEAS.

“There are huge supply-chain issues where some materials needed to reopen are still hard to get, so how do we coordinate and ensure labs have the resources they need to reopen?” said Sarah Lyn Elwell, the FAS director of research operations for science. “Other logistical concerns were on bringing back our core facilities [like our DNA-sequencing core or our Center for Nanoscale Systems]. … These are shared resources that our faculty and researchers heavily depend upon for their research. … [We also did] HVAC surveys of the buildings to understand airflow and air changes and how many people we can have in different spaces. It’s been a whole myriad of components.”

The return has also involved a steady rollout of new protocols and safety measures. These include guidance on density (which must remain at 25 percent or less), proper use of lab space to maintain proper social distancing at all times, scheduling to keep density low, cleaning procedures for shared surfaces and equipment, self-evaluation on COVID symptoms, and guidelines on when to get tested.

For instance, to enter any research buildings, faculty and staff have to complete daily COVID-19 screening on Harvard’s health-reporting website, Crimson Clear. Within two weeks of returning to the labs, they also must be tested for the virus by Harvard University Health Services.

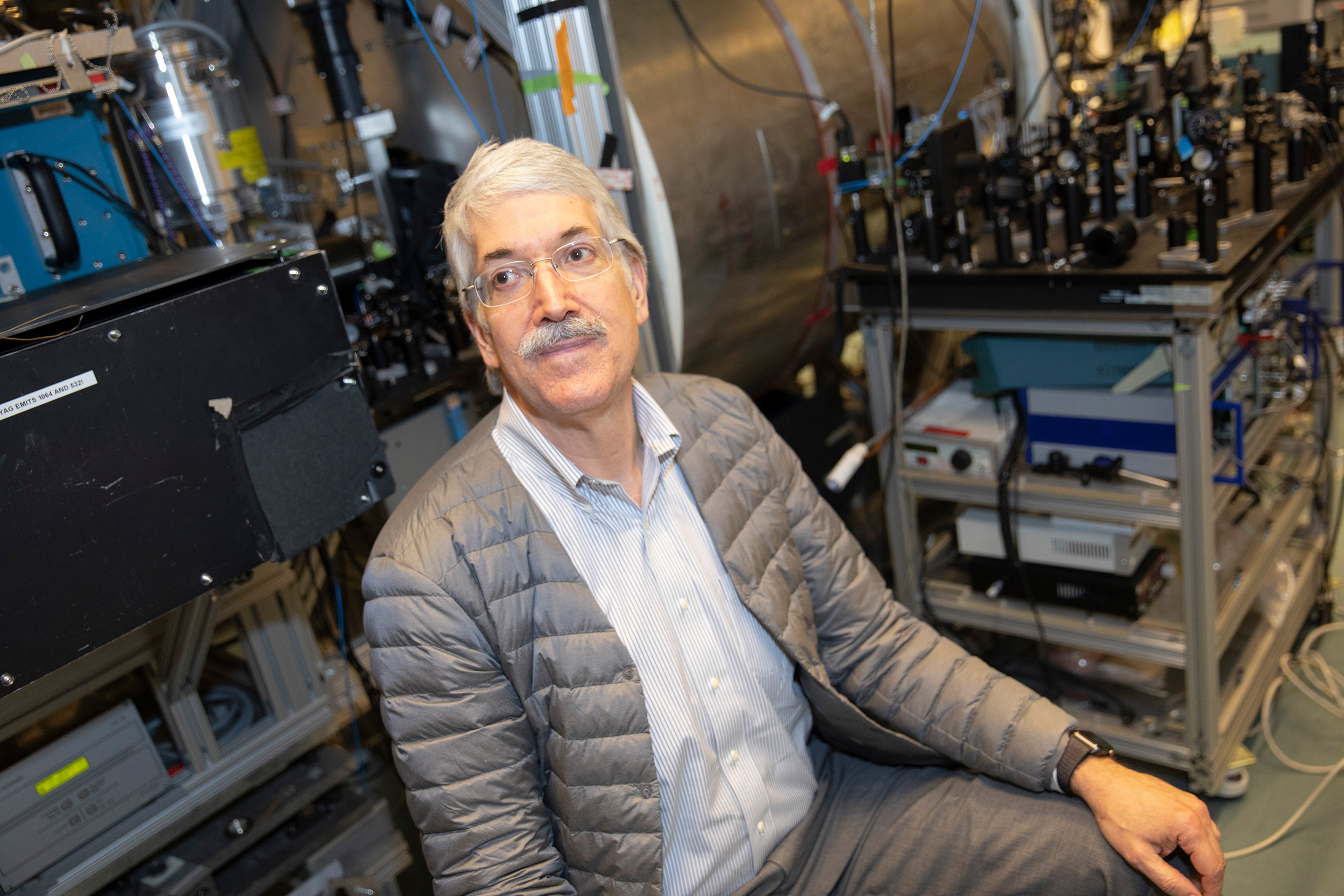

“Being displaced from the lab is not a natural thing for experimentalists,” said John Doyle, the Henry B. Silsbee Professor of Physics.

File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff

Researchers will continue doing whatever work they can from home, like analysis and computation, and save lab time for experiments. Protocols also exist on eating meals and bathroom use.

Each lab developed its own plan for how to meet overarching guidelines, and FAS and SEAS administration then approved them. Details vary by lab. Some have implemented morning and evening shifts to keep density low, and others are rotating the personnel allowed to go into the labs every few weeks.

“The idea is that if any one person shows symptoms or gets sick, only their shift and rotation has to isolate, and not the whole lab,” said Matthew Volpe, a fourth-year graduate student who works in the Balskus Lab in the FAS Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology.

Among the researchers themselves, the return has many levels of meaning. It’s about getting back into the scientific setting, returning to work they are passionate about, and getting closer to the next steps in their education and career.

“Being displaced from the lab is not a natural thing for experimentalists,” said John Doyle, the Henry B. Silsbee Professor of Physics. “This return is getting back to doing the work that they want to do. It’s what their profession is.”

Doyle’s team, which works with high-precision optics, spent the first few days getting temperature, humidity, and dust levels in the lab to precise levels so their experiments can get clean results. They also spent time tinkering with the lab’s lasers to make sure they were all still working.

“I’ve been missing doing experiments with my hands,” said Dhananjay Bambah-Mukku, a postdoctoral fellow in the Dulac Lab. “I relied on baking to be doing some sort of experiments at home, but I’m very glad to be back in the lab and doing [scientific] experiments, which is really what I love doing.”

Megan He, a graduate student in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology’s Hsu Lab, missed working with her hands, too. There’s only so much that wet lab biologists can do sitting in front of a computer, she said, but admits the time away was useful.

“It really was good to take some time and read some papers and think a little bit more about my projects,” said He, who studies the stem cells that determine skin and hair color. “All this is very important to generating new hypotheses and thinking about what are the most urgent experiments you need to address.”

Other graduate students who are just getting their feet in the research world, like He, described what getting back means toward their degree.

“To progress through my program, I need to go back to the lab to make progress on my project,” said Ally Freedy, a graduate student in Harvard MIT M.D.-Ph.D. Program working in the Liau Lab, where she studies how epigenetics intersects with cancer therapy. “It’s especially important for me to progress through my program because I have two years of medical school left after I finish my Ph.D. [in the chemical biology program at Harvard].”

Volpe, from the Balskus Lab, expressed similar sentiments, including mixed feelings on going back in the middle of a pandemic. But, like many others, he feels safe with the return plans. In fact, when he gets back into the lab in two weeks as part of the second rotation, he’s looking forward to seeing some of his co-workers — from a safe distance.

“It will be nice to see physically see them and not through a Zoom screen,” he said. “It’s funny. As a graduate student, you spend a lot of time complaining about the lab and then when you’re told you can’t go into the lab, it seems like a much nicer place that you want to be in.”