Mary Ingraham Bunting (standing) speaks at the Radcliffe Institute.

Photo by Charles M. Hagen

A ‘messy experiment’

New book explores the early years of Radcliffe though the lives of five of its first fellows

It was called “a messy experiment” by its founder. It became a hub of creativity that helped propel forward the women it engaged, and the women’s movement, in crucial ways.

The timing was right for Mary Ingraham Bunting and her audacious new plan. It was 1960, and a cultural war had been brewing since the late 1950s. Women were seeking higher education in increasing numbers and pushing back against strict gender roles in the home and the workplace, and the approval of the birth control pill by the Food and Drug Administration in 1959 was allowing them, for the first time, to take charge of their child-bearing years and careers.

That was the backdrop against which “Polly” Bunting, the newly minted president of Radcliffe College, launched the new Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study (since reincarnated as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study). A microbiologist by training, Bunting was eager to create a place for women whose academic and professional lives had been put on hold by the demands of motherhood and family life. She dreamed of a space where promising, high-achieving women could study, research, write, read, and find community with like-minded peers. These “intellectually displaced women” would receive a stipend to spend as they wished, an office, access to Harvard’s libraries and professors, and the gift of unfettered time.

Author Maggie Doherty chronicles that shift in her new book, “The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship, and Liberation in the 1960s.” The work charts the story of the center’s infancy through the lives of five of its earliest fellows: poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin; writer and labor activist Tillie Olsen; sculptor Mariana Pineda; and painter Barbara Swan. Their time at the Institute, and with one another, would shape their future successes, and their work would influence the early women’s liberation movement and later inform and inspire new expressions of women’s equality and empowerment.

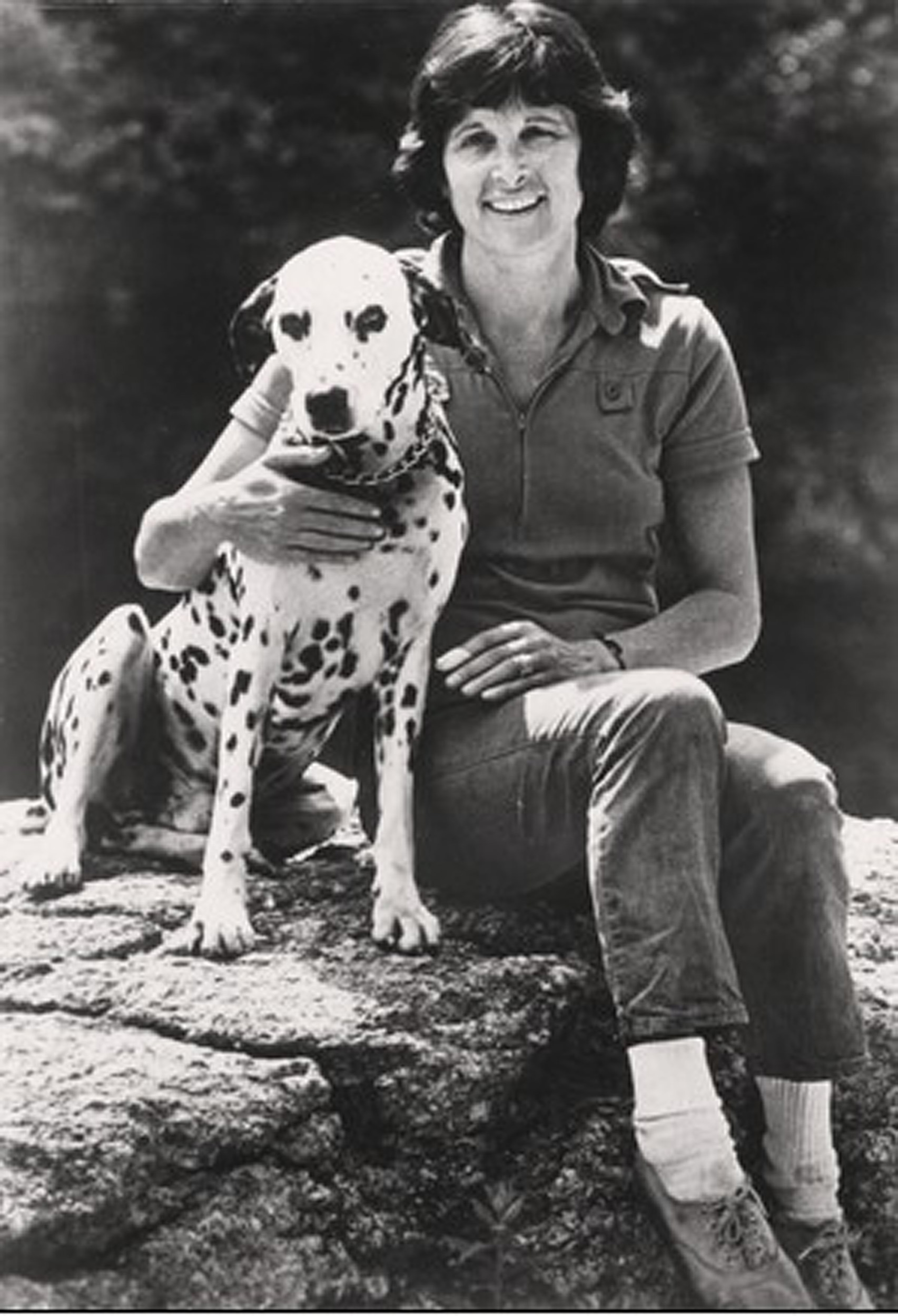

Maxine Kumin (with dog) and Anne Sexton.

Courtesy of the Radcliffe Archive

“[They were] breaking new ground for women’s liberation in ways that I don’t think any of the individual actors necessarily anticipated or were even fully conscious of,” said Doherty, Ph.D. ’15, who stumbled on the Institute’s origin story while researching Olsen during her graduate work. Bunting, the fellows, and a range of other actors, said Doherty, were “moving in the direction of this really new kind of political and social consciousness and activism.”

Kumin and Sexton — each of whom would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize for poetry — used their words to expose the unglamorous, and often ugly sides of womanhood. “Sexton’s great poetic intervention — the presentation of messy female experience as art — was also a political one. In writing about these topics before they entered public discourse, she was an inspiration and ahead of her time,” writes Doherty.

Swan, a portraitist who studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, used her brush to capture the “strangeness — the surreality — of motherhood” in a painting that accompanied her Radcliffe application. “Her representation of motherhood was not quotidian or banal or uninspired; it was groundbreaking, spiritual, unnerving,” writes Doherty. Similarly, Pineda’s sculptures, with their representations of the female body as a “vessel for knowledge,” tapped into the Institute’s “spirit of discovery.”

Olsen was a leftist, feminist labor organizer, and a mother of four who had to work to support her family. She used a nearly two-hour presentation on creativity delivered during her fellowship as an important springboard. The long, somewhat rambling discourse left many in the audience “restless and annoyed,” but it was also the beginning of “an intellectual project that would consume the rest of [her] working life,” writes Doherty.

Tillie Olsen (second from left) meets with students at North House.

Photo by Rick Stafford

The most political of the five, Olsen’s talk turned a light on the Institute’s early blind spot: working women who lacked the means of their better-off contemporaries. For such women, a college degree, let alone a doctorate or a shot at a fellowship, Olsen knew, was largely out of reach. (The five women took the name of their group from the Radcliffe application requirement that called for candidates to possess either a Ph.D. or its equivalent in creative achievement.)

In later years Olsen’s book “Silences” helped redefine the literary canon, giving voice to female writers and those from the working class. She also became a champion of curriculum reform, teaching and advocating for courses that included work by women, working-class writers, and writers of color. “[Olsen] was not in her lifetime the most successful, nor the kindest, nor necessarily the most talented,” writes Doherty. “But she saw the world differently from the other four women: she saw how creativity arises from material circumstances, how power is wielded against the vulnerable, and — crucially — how class, gender, and race intersect.”

Doherty’s book doesn’t shy from noting irony. She writes that many talented women who secured Radcliffe fellowships were guided and often cowed by male instructors early in their careers, and that her five subjects helped advance a campaign in which they couldn’t fully participate. “The Equivalents were women born too early; by the time the women’s movement gained full steam, each of them was well established in her life and ways,” she writes.

Still, their contributions were crucial. By simply participating in the Institute and tackling topics so fundamental to the movement, like motherhood and the challenges of the working woman, in their writing and art, they helped encourage equality and redefine art both then and now, said Doherty.

“The kind of precedent that I think they set as artists, about what you can make high or refined art, lyric poetry, sculpture, fantastic oil painting about — your most intimate private life as a woman — I think we see that today. That’s one of their main gifts to us as a generation.”