A day in the life of an ER doc

Third-year resident Anita Chary describes the personal and professional trials brought by the pandemic

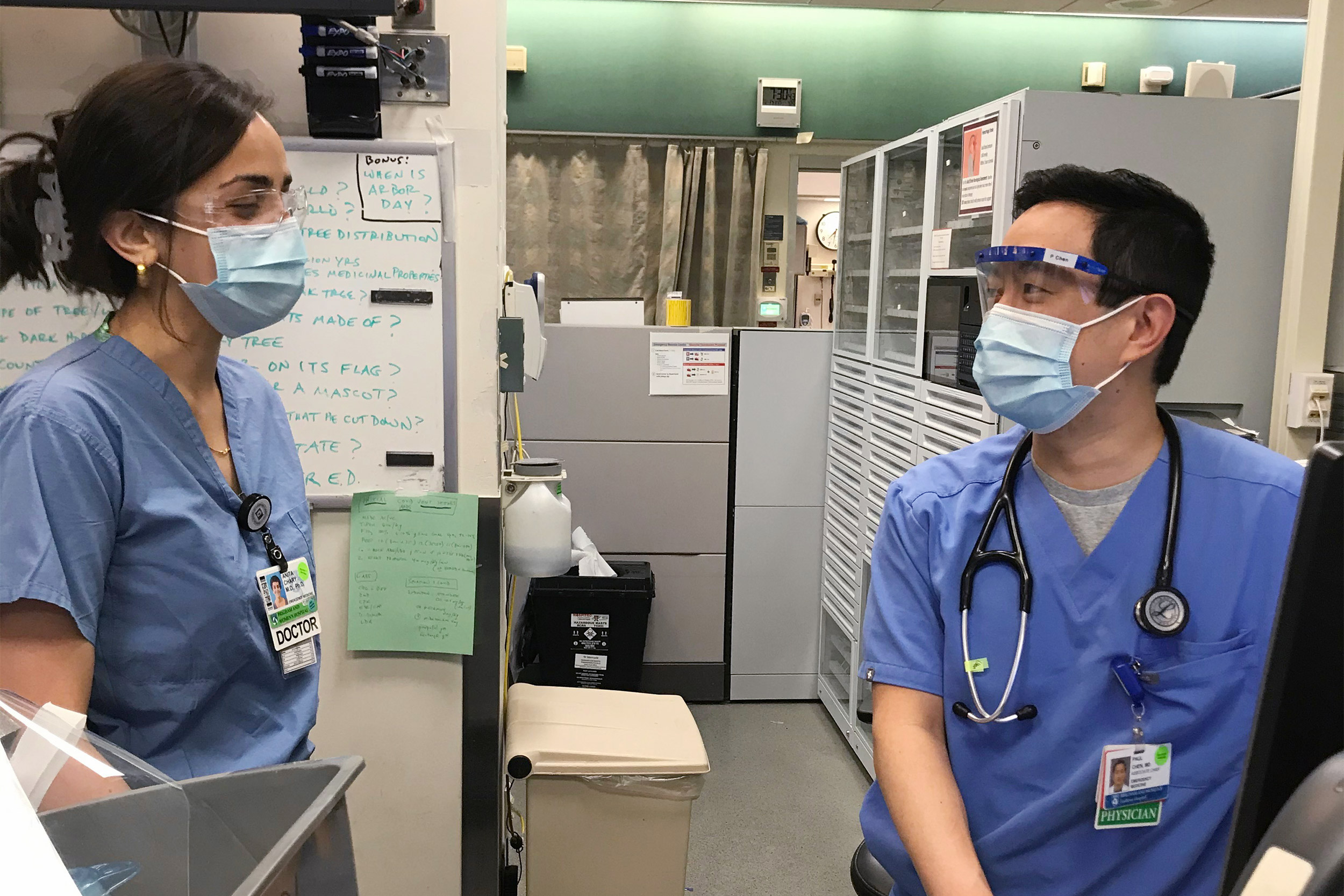

Anita Chary in the hospital’s trauma bay. Most of the patients she sees this day will arrive with COVID-19 or symptoms of the illness.

Photos courtesy of Anita Chary

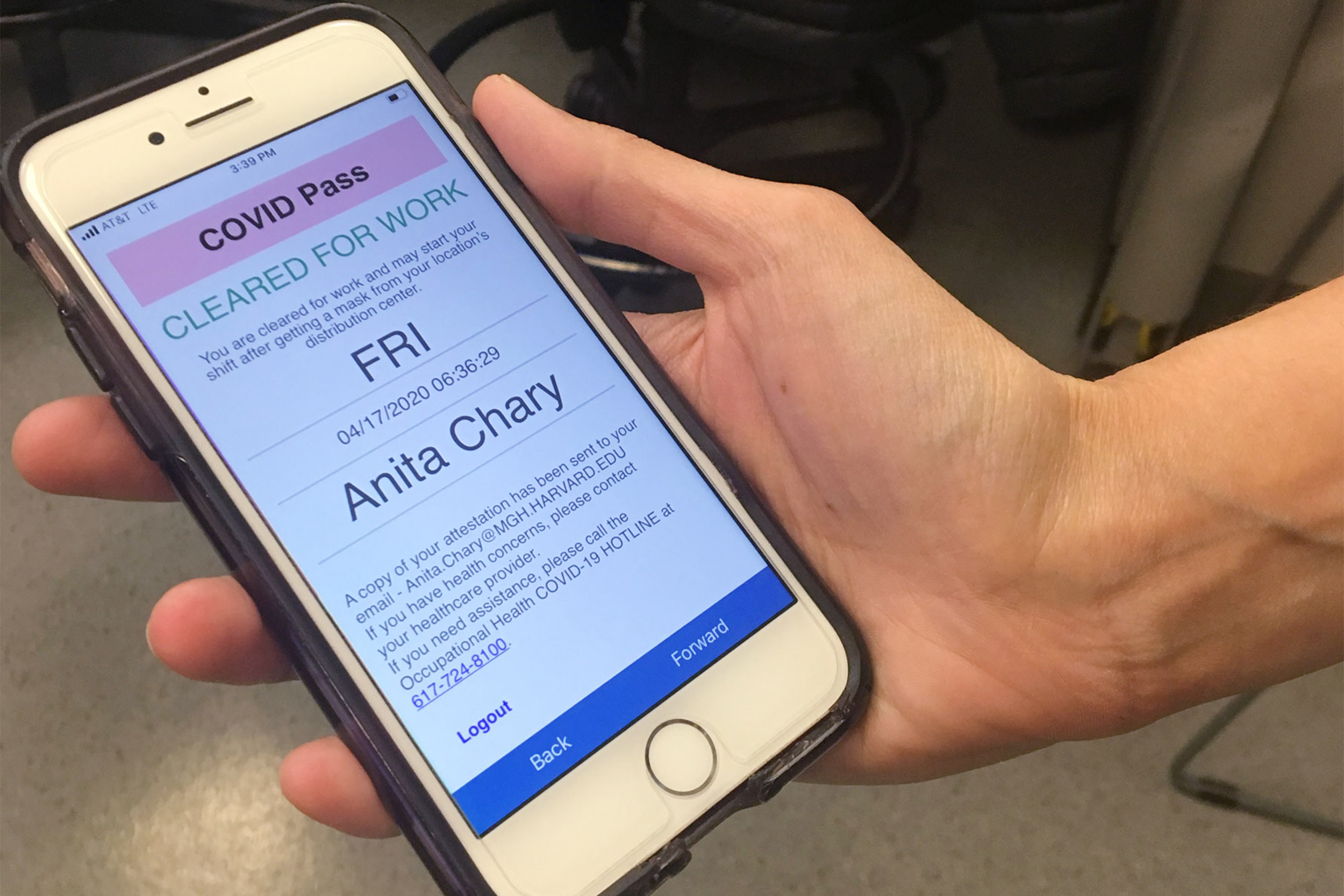

It’s cold outside as Anita Chary makes the short walk from her apartment to the Longwood Medical Area. Just before her 7 a.m. start time she arrives at one of the designated Brigham and Women’s staff entrances on Francis Street and holds up her smartphone. A health care worker checks Chary’s symptom-tracker app to ensure she completed the checklist of questions. The top of the screen reads “Cleared for work,” in bold green letters. “If you are positive for any symptoms” of COVID-19, Chary says, “you can’t enter the building.”

She is given a mask to wear, then winds her way through tunnels to her department, where she dons blue scrubs, face shield, and goggles and begins another nine-hour shift in an emergency room, the front line of the nation’s worst public health crisis in more than a century. Chary, who is in her third of four years at the Brigham and Women’s/Massachusetts General Hospital Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency program, will see fewer people than she would have during a normal shift only a couple of months ago. But these days are anything but normal, she says as she details what now passes for a typical day. Most arrive with complications related to the novel coronavirus, requiring more involved, sometimes intensive treatment.

As she has done so often in recent weeks, Chary divides patients suffering with symptoms of the virus, or with a positive diagnosis, into three categories: those who are well enough to leave and recover at home; those who must be admitted because they need oxygen to help them breathe; and those who need intensive care and a ventilator.

Most of her patients today fall into the first two categories, including a woman returning to the ER who tested positive for coronavirus and is still struggling with symptoms. Chary checks her oxygen levels and finds they are normal. As she prepares to release her, she notices the fear in the woman’s eyes. Since her diagnosis, many of the woman’s family members have ended up in the ICU, Chary says later, and she has others still at home in need of her care. The same is true for many who arrive at the ER not sick enough to be hospitalized. Chary watches them leave tortured by the thought of infecting loved ones. “It’s the prospect of going home and potentially spreading coronavirus to other people at home that is just so difficult for them to bear.”

Aware there are always other patients who need her, Chary keeps her emotions close at the hospital. After work, at home alone, it’s harder to hold them down. It’s been months since she has seen her husband, a pediatric doctor in an intensive care unit in Houston. Her sleep has suffered, she says, the result of an overwhelming need to check her patients’ electronic charts for updates. “I try to do it before I go to bed at night; it’s the first thing I do in the morning. It’s just this higher level of constant concern about the patients that I’ve had.”

She worries about them all but is burdened by some more than others. “With younger patients it can be particularly devastating when you see they are still not doing better after being in the ICU for weeks.”

And then there is the influx of lower-income patients from communities of color.

“I often find that these patients are working in essential jobs,” she says. “They are working in grocery stores; they are operating public transport; they’re in custodial services; or they’re doing things like home delivery. And so they’re really on the front lines of society just as much as we are in the hospital. Working from home is not an option. And it’s also difficult for them to do social distancing and isolate because they live in smaller apartments, and they tend to live in multigenerational households where people are sick, too.”

Chary knows death comes with being a doctor specializing in urgent care, but some of the unique aspects of this disease can still shake her. Many physicians have noted how quickly conditions can deteriorate and the high death rates for those placed on ventilators. Among the patients Chary has lost to the disease in recent weeks was an elderly woman she had to place on the device to pump air in and out of her lungs. “I knew that the likelihood that she would recover was very, very low, and I think there is a weight that you feel when you sense that you are going to be the last person to talk to someone or spend any time with that person when they are awake and alert.”

At the urging of the hospital’s palliative-care team, Chary and her colleagues are having patients requiring a ventilator record messages to loved ones on their phones before they are sedated. “That has been one of the most powerful experiences,” says Chary, her voice shaking. “Handing someone their phone and listening to them tell their family they love them and just hoping that they will be able to speak to their loved ones again after they come off the ventilator, but not knowing.”

Nonetheless, Chary considers herself lucky. She’s heard horror stories from friends and colleagues in places like New York City and Detroit, where refrigerated trucks idle outside hospitals storing the bodies of those who have passed away, while inside patients overwhelm sickbays, sometimes dying before a doctor can get to them. Working conditions in Boston have not gotten to that level even though Massachusetts is a hot spot in the nationwide epidemic. As of Tuesday, the state Department of Health put the total number of cases at 58,302, with 3,153 deaths.

“I think my sense of duty to respond to a crisis has kind of superseded the anxieties about personally falling sick.”

Anita Chary

In Chary’s ER, there are no patients languishing in hallways, no desperate lack of personal protection equipment (PPE), or ventilators. The volume of patients in the Brigham and Women’s ER has dropped in recent weeks. Chary, the department’s incoming chief resident, typically sees 15 to 20 patients per shift. Today that number has been cut in half. Fear of contracting the virus has kept away many patients with relatively minor injuries.

On a positive note, this day Chary, sends another of her non-acute COVID-19 patients to Boston Hope Medical Center, where they can recover in isolation. The makeshift facility with 1,000 beds reserved for noncritical patients and members of the city’s homeless population is located at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center in the Seaport District. “That was a wonderful alternative,” says Chary, who is also a clinical fellow in emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The young doctor says careful planning has been the key to the Brigham’s response to the pandemic — the hospital had 159 inpatients with 90 of them requiring intensive care, according to its website notes on Tuesday. Chary said she has access to the gowns, gloves, masks, face shields, and head coverings she needs, along with a reduced work schedule — an effort by administrators to keep the workforce as safe and healthy as possible. To further limit infection rates, the hospital, anticipating a surge in coronavirus cases, erected walls in its emergency department, creating individual rooms for incoming patients.

“The Brigham has been doing a lot of innovation and development and planning around how to best respond to this crisis,” said Chary, who notes the same is true at Massachusetts General Hospital, where she also rotates through the ER. “Our experience has been different because we actually have the institutional resources to take care of the patients who are arriving in our emergency departments.”

Still, limiting her and her colleagues’ exposure to the virus is a constant concern. Chary keeps to the strict protocol she has followed for the past several weeks, calling patients by phone from outside their rooms to determine whether they might be infected. “Sometimes patients report something to the triage nurse out front, but they deny [coronavirus] symptoms,” she said. “Then when you talk to them more, it sounds like maybe they actually do have symptoms.” Their answers determine whether Chary will fully suit up in PPE before entering.

Despite the precautions, health care workers, by the very nature of their roles, face a higher risk. A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that more than 9,000 health professionals had been infected by the coronavirus, including more than 320 at the Brigham.

A handful of Chary’s colleagues have tested positive in recent weeks and self-quarantined. “I feel like I just have to be resilient in the moment and hope for the best, and hope to be lucky,” Chary says, “and I think my sense of duty to respond to a crisis has kind of superseded the anxieties about personally falling sick.”

“I grew up in a Hindu household, and my parents always emphasized serving society. “We also had this saying: ‘Hands that serve are holier than lips that pray.’”

Anita Chary

The challenges are many. Chary learns that an ambulance is racing to the hospital with a patient whose heart has stopped. She knows minutes matter and that an on-site test for coronavirus would take hours. So she assumes the patient is positive and gets on with her job, well aware that CPR carries a greater risk of spreading the liquid droplets that contain the virus, increasing the chance of transmission.

“In the past, there would be a many-hands-on-deck approach,” says Chary. “But with coronavirus, when these sorts of things happen, we have to be really mindful about the risks that could happen with exposure to a greater number of staff. Everything gets very well defined up front in terms of exactly how many people we are going to have in the room, who is going to be doing what, and how can we minimize the number of people who need to be potentially exposed.”

Unable to resuscitate the patient, the uncertainty about infection lingers. “Not knowing if this person died because of coronavirus complications is difficult for the family, and for the care team,” says Chary.

Many might find facing a massive public health crisis so early in a medical career daunting. Chary isn’t one of them. “I actually feel very privileged and lucky that I can be among the physicians who are serving patients in this time, when they truly need us to take care of them. I think many people go into medicine with this desire to heal the sick, and I feel like I’ve never been prouder to be a physician.”

And there are bright moments.

She sees hope in the triage unit at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, where she can send people to recover so they don’t put their loved ones at risk. She also sees it in the efforts hospital staff make to connect with community members through virtual meetings that offer a range of languages in which to learn about the virus and the best ways to stay safe. And she finds hope in the efforts of her colleagues who follow up on patients sent home from the ER with phone calls and virtual visits.

“My colleagues are inspiring, and it’s really wonderful to be a witness and a participant in this time of great innovation and this time of people coming together.” Still, she adds, “there remains that uncertainty and that anxiety about the patients and how they’re doing.”

When her shift ends at 4 p.m. Chary prepares to head out, disinfecting her phone and stethoscope with sanitizer, meticulously washing her hands and arms up to her elbows, and changing out of her blue scrubs into clean clothes. Back in her apartment she showers as soon as she walks in, a normal part of her daily routine in the age of coronavirus.

Chary unwinds with Netflix and calls to family. Her parents in Illinois are in the high-risk category, over the age of 65 with underlying health conditions, and, as with her husband, she hasn’t seen them for months. “It’s hard, but the safest thing for myself, my loved ones, and society is to not travel right now,” Chary says.

It will be a couple of days before she returns for another shift in the ER. Chary will repeat her favorite mantra — “I will do good in the world today” — before heading out. “I grew up in a Hindu household, and my parents always emphasized serving society,” she says. “We also had this saying: ‘Hands that serve are holier than lips that pray.’”

As she departs her apartment each morning, she sees another reminder of her mission staring back at her.

“It’s a drawing of a woman with a stethoscope by my two young nieces,” she says. “I hung it on my door so it’s something that I see when I leave the house every day. It’s a little positive affirmation that I am doing something meaningful.”