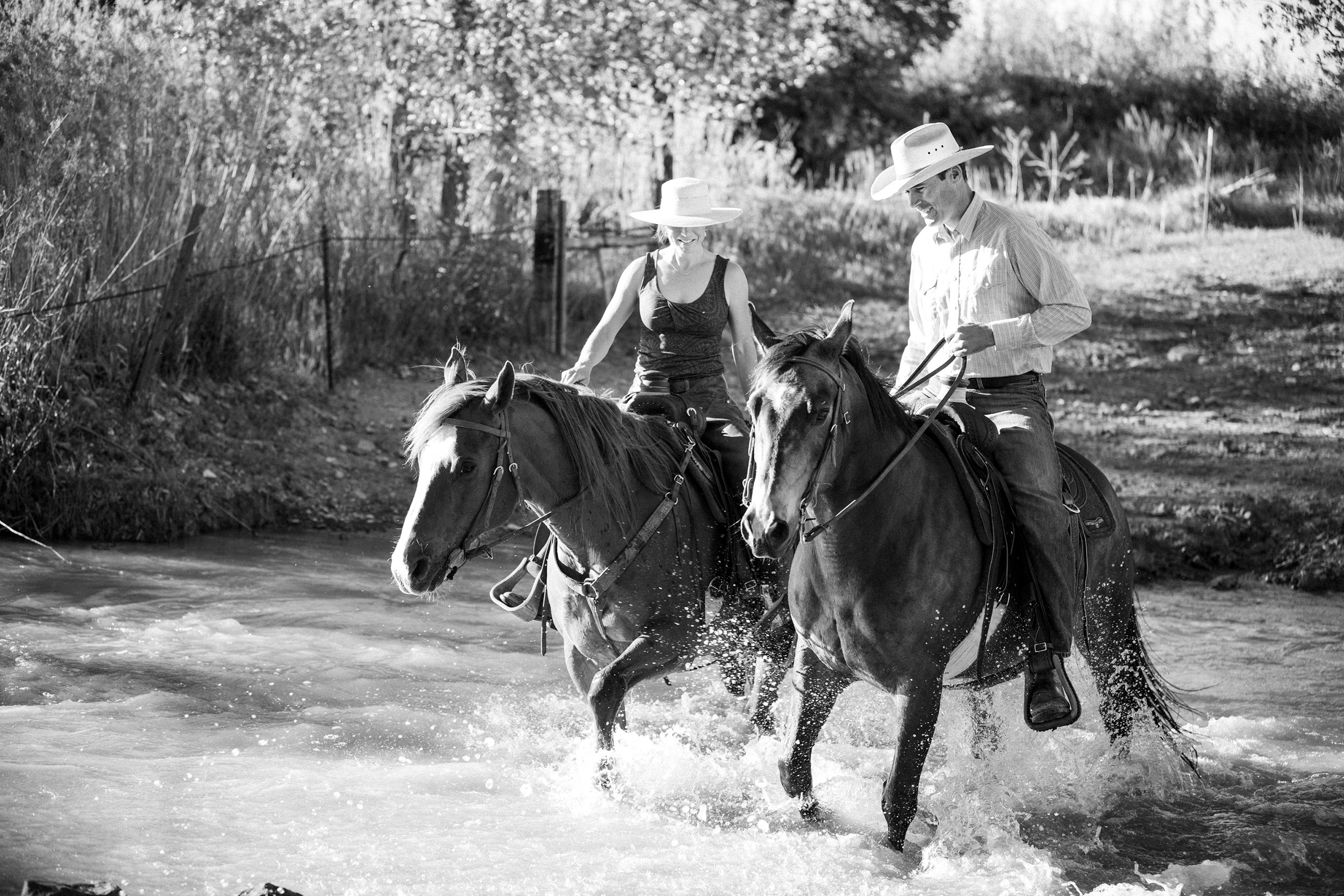

Alex Blake (right) riding horses with his wife, Abby Nelson.

Photos by Mery Donald (2016)

Sustainability in Big Sky Country

A cattleman who grew up on a ranch talks about the interdependence of financial and environmental viability

The young Blake family left Boston and moved to Big Timber, Mont., in the early 1970s to try their luck at cattle ranching. Since then, Francis ’61, Sandi, and their sons, Peter ’93, Alex ’96, and Amory ’98 (who was born a few years after the move) have spent the better part of five decades turning a patch of unloved dirt into a ranch and nursery built for sustainability. Alex, who was just a month old when he arrived in Montana, now runs day-to-day operations with help from his father and younger brother, Amory. He says that his parents recognized early on that the long-term viability of the business would depend on embracing smart conservation practices. The Gazette recently spoke with Alex, who was an economics concentrator and heavyweight crew team captain at Harvard, about the business and his views on the future of regenerative ranching in Montana, and across the country.

Q&A

Alex Blake

GAZETTE: When did your family start thinking about the importance of sustainable practices?

BLAKE: My parents realized soon after they moved our family here in 1973 that protecting our grasslands and conserving our precious soils and water resources was really important in making this ranch viable. In the early years they started fencing off riparian areas and adopting rotational grazing practices. They formalized their efforts to this end in the mid-1980s when my dad attended holistic resource management trainings, which promote “healthy land, healthy food, and healthy lives,” and further realized that there were some alternatives to the traditional practices that were in favor at the time.

At the same time my mother, who started the nursery in 1977, was seeing increasing demand for native hardy plants and recognized that there were very few, if any, nurseries in the area that were growing and promoting their use in landscaping. There was a clear need for these types of trees, shrubs, and perennials, and she had a strong interest in them, so this was a clear business opportunity for the nursery. Native plants tend to thrive in harsh Montana conditions that can include extreme cold, difficult soil, drought, and heat, as they need a lot less water than many non-native species that are introduced, and which can at times outcompete, or even take over landscapes. My brother Amory now runs the nursery (with valuable support from our mother) and he has continued this emphasis on plants that will thrive in our challenging environment.

GAZETTE: Environmental concerns were only beginning to catch on in the 1970s. So was there something about the ranch itself that made your parents so aware of the need for sustainable practices?

BLAKE: Our ranch is not large by Montana standards, and we have had limited baseline soil and water resources from the outset, so conserving and hopefully improving what we had was important from day one. We want to give future generations the opportunity to continue living and working on this land. Considering changing climate conditions and uncertainties in our cattle markets, that may not be an option without good management practices. We also care a lot about maintaining open spaces and keeping ranch lands and farmland intact, so not getting ourselves in a financial position where we’d have to consider subdividing has also been an incentive to manage as best as we can. What will make our ranch sustainable in the long term is our ability to work together as family and pursue these passions of ours here on this landscape. I really like that I get to work cattle with my wife, Abby, and other family members, and now my 11-month-old daughter, Mabel, is often along for the ride. It is powerful to share these enjoyable and sometimes challenging aspects of ranching with people we love.

GAZETTE: What are some examples of the sustainable practices you employ?

The Blakes’ red angus and black angus cattle backed by the Crazy Mountains.

Photo by Lynn Donaldson

BLAKE: We use regenerative grazing practices that attempt to mimic how this landscape historically would have been used by bison. In practice this means short-duration, high-intensity grazing with an emphasis on long rest periods. Our native landscapes in Montana need grazing; the types of species of plant life that grow in Montana don’t always do well when left to their own devices. A limited amount of grazing can stimulate plant growth, clean up old dead grasses, and as this happens, encourage deeper root growth and nutrient cycling.

We have also built a low-input cow herd that fits our environment (low annual precipitation, hot, dry summers, and, historically, cold and snowy winters) and have moved our calving dates to be in sync with our grass resources and more favorable weather. So instead of the traditional February/March calving season, we now calve in May/June when the cows are on better grass (which means there’s less need for feeding hay) and the calves aren’t potentially being born in the middle of a blizzard. As a result of these changes we have almost no sickness in our cows and calves, and we have drastically reduced the need for antibiotics. In addition, we don’t use any hormones in our cattle.

GAZETTE: Have you also been able to incorporate new technologies?

BLAKE: In terms of powering the farm and nursery, we’ve installed solar panels for tasks like pumping livestock and irrigation water and for powering one of the homes and several outbuildings on the ranch. The nursery has specialized in low-input (drought-tolerant, winter-hardy) and native trees and shrubs for years and we work hard to promote practical landscaping that fits our harsh environment. We have completely eliminated synthetic fertilizers from the ranch and have significantly reduced our use of chemicals (herbicides and pesticides) in both the ranch and nursery.

Recently, we started using an app called MaiaGrazing that allows us to track livestock movements and forage resources in real time. We’re also doing more soil sampling that will allow us to receive payments for carbon sequestered as a result of our grazing practices. When we do have to reseed pastures, we now use no-till techniques; this means that, through timed grazing and the use of cover crops, we’re able to avoid disturbing the soil, and we’ve stopped using the herbicides that are typically associated with reseeding. We’ve also recently installed a center-pivot irrigation system that will significantly reduce our irrigation water use. And we’re waiting for my older brother, Peter, to deliver a drone (he works in the industry) to help us find missing cows and to better monitor our range conditions.

GAZETTE: Do you have specific goals and targets that you try to strive for?

“I’m optimistic about the future of regenerative ranching as younger generations see the imperative to be better stewards of our land, water, and wildlife resources.”

BLAKE: While we have a long way to go on this front, our long-term goal is to restore our rangelands to their historic potential. This would mean much greater plant diversity, increased soil organic matter, better wildlife habitat, and ultimately healthier, happier cows. Some of the specific goals and targets that we think about are increasing our livestock carrying capacity through better grazing management, further reducing the need for livestock (hay, protein supplements) and chemical (herbicide and pesticide) inputs, and developing a herd that’s a better fit for our environment (smaller-framed, better adapted to our harsh summer and winter climate). Through our involvement in a soil carbon program we’re taking a lot of baseline soil samples that will allow us to track organic matter and soil carbon levels. The program has a 30-year commitment, and we hope to see significant improvements over that time period. All of these goals tie directly to our bottom line. Considering the relatively small scale of our operation, we know that without making continuous improvements to our management skill set and on-the-ground practices we’ll have a hard time keeping this ranch economically viable.

In the spirit of enterprise diversity, we’ve also developed a grass-fed beef program that will improve financial returns on our cattle herd. We sell directly to consumers who are interested in supporting our care for the land and animals. These animals are finished here on grass, never in feedlots, are handled using low-stress herding techniques, and have never received hormones or antibiotics, so we feel confident that we’re selling a great product. Ultimately, we would like to market all of our cattle through this program or a grass-fed beef cooperative that shares these management principles and values.

GAZETTE: Talk about the climate of sustainable ranching, and your place, in the state of Montana.

BLAKE: We consider ourselves fortunate to be working with many like-minded partners in the sustainable/regenerative ag movement. I work part-time with a great nonprofit called Western Sustainability Exchange (WSE) that’s providing resources to ranchers using regenerative practices, and there’s a great network of progressive ranchers spread across the state and region who are alumni of schools and workshops that promote sharing ideas and alternative management strategies. We’re still a very small percentage of the overall ranching community (and I want to acknowledge that many/most of the “traditional” ranchers care a lot about conservation and good management practices too), but I think the movement has been gaining a lot of interest as producers become more aware of the realities of climate change and resource scarcity.

GAZETTE: What is the future of sustainable ranching more broadly?

BLAKE: I’m really excited about the growing interest in understanding soil health and learning about how we can build and restore healthy soils on our native grasslands. A soil health conference held in Billings a few months ago drew close to 400 participants. That same conference drew only about 50 participants just a few years ago. We see similar interest in WSE workshops that address grazing management, low-stress livestock handling, and “drought-proofing” ranches, among other topics, so I’m optimistic about the future of regenerative ranching as younger generations see the imperative to be better stewards of our land, water, and wildlife resources.

We know that consumers are also demanding more accountability in how land and livestock are managed, so being in a position to meet and document these expectations is important for the future of our industry. In my opinion, the potential for building soil organic matter and carbon sequestration though better grazing management is one of the biggest and most important developments in our industry. This is why we’re really excited to be one of the first ranches to sign up with a new grasslands soil carbon program, which will pay us for verified sequestered carbon. This program is unique because it also provides up-front funding for infrastructure improvements, through stock water and fencing, that will increase our ability to manage our grazing.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.