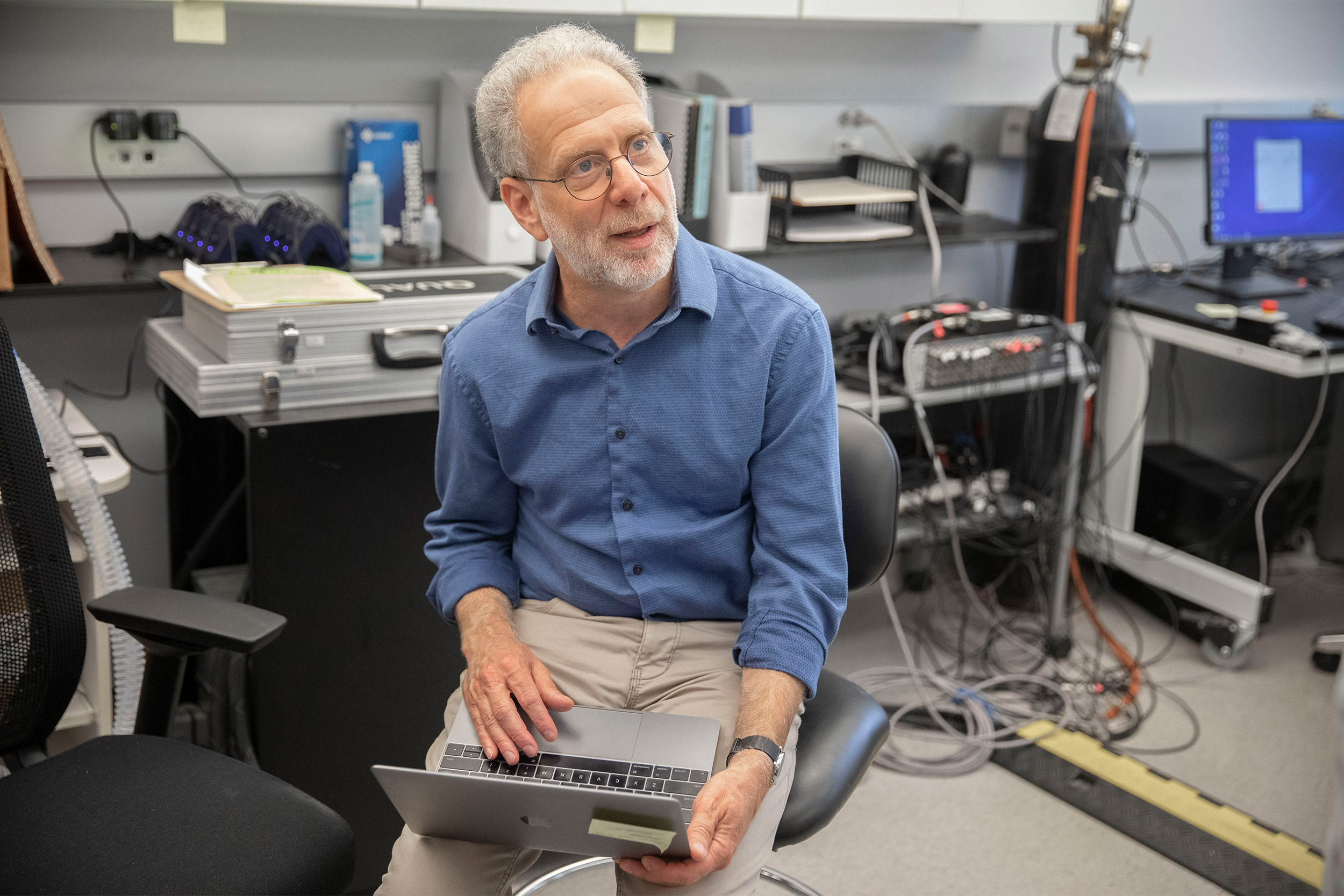

Professor Daniel E. Lieberman is incorporating the coronavirus as part of his curriculum.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Studying COVID-19 in real time

Across a range of disciplines, from medicine to history, biology to business, the crisis has become a living part of the curriculum

The coronavirus has had a huge impact on Daniel E. Lieberman’s class on human evolution and human health. And not just because it’s upended the lives of his 91 students and moved the lecture course online.

The virus is now a major class topic and a routine focus of lesson plans and discussions. That has helped both him and his students process the crisis and engage in real-world learning, said the Edwin M. Lerner II Professor of Biological Science. And he isn’t alone in thinking how to incorporate it into the curriculum.

“You could ask: How could we not?” said Mark Fishman, professor of stem cell and regenerative biology. “COVID-19 is changing the landscape of everything that we value completely.”

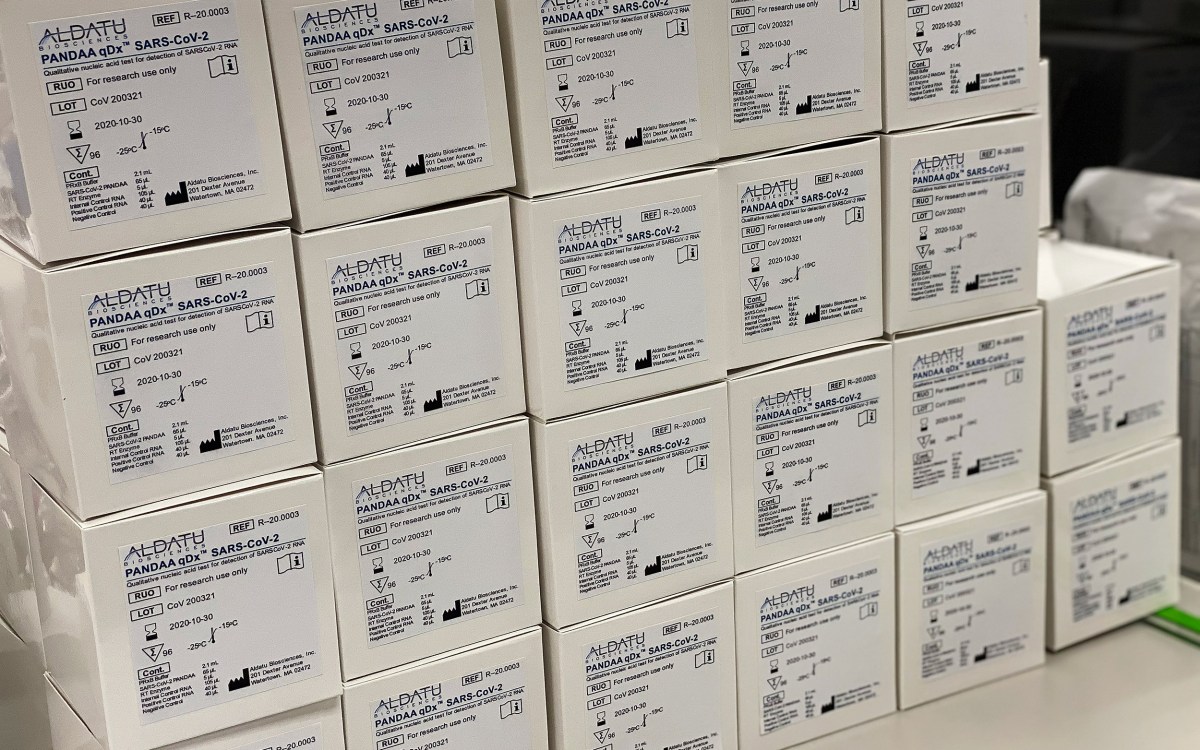

Fishman and others are in the early stages of planning a new course on the novel coronavirus. It would be for the newly launched M.S./M.B.A. Biotechnology: Life Sciences program. The program offers a joint degree from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the Business School, the Medical School, and the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

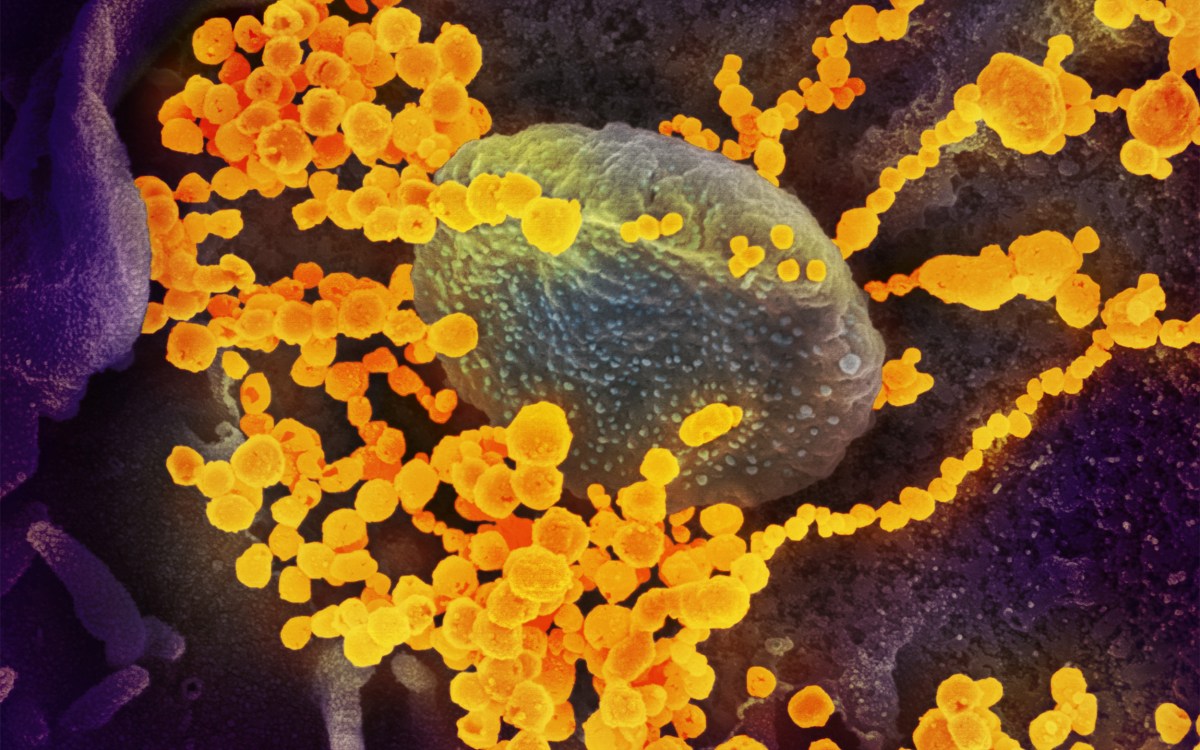

The new course will focus on the biology and medicine around SARS-CoV-2, the official name of the virus that causes COVID-19. If the lab course currently planned for the summer is delayed, this course could take its place.

“The plan would be to focus on the virus, its interaction with cells, and the therapeutic, epidemiological, and ethical challenges of the pandemic,” Fishman said. “The implications are profound, current, important, and emotionally gripping, and of direct relevance to anyone planning a career in biomedicine.”

Rachel Carmody, an assistant professor in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, has added new content on bacterial and viral interactions.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Rachel Carmody teaches a class on gut microbes and their effects on human health. The microorganisms perform many functions, among them drug metabolism, so they may contribute to risks and complications of certain diseases like COVID-19. Carmody, an assistant professor in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, has expanded her lessons on these topics in light of the pandemic. She’s also added new content on bacterial and viral interactions.

In the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Assistant Professor Marine Denolle’s teaching assistant had students analyze noise-level data from a city in China that was locked down. Tim Clements, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, assigned the project as homework in the earthquake and tectonics class. Students downloaded seismic data from Enshi City in central China, which has a population of 750,000. They noticed that during the lockdown, noise levels were similar to that of a rural area. “It got down to, basically, the natural level you would expect when there are no humans around,” Clements said.

In a popular course on world health challenges, there was no way of neglecting COVID-19, said Sue J. Goldie, the Roger Irving Lee Professor of Public Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Goldie regularly pulls contemporary events into the class, which places an emphasis on transnational risks. She often revises the curriculum on the fly, as she did during the Zika virus epidemic. This pandemic is no different.

Chan School Professor Sue J. Goldie regularly pulls contemporary events into her class, revising the curriculum on the fly, as she did during the Zika virus epidemic.

File photo by Ann Wang

“An important attribute of this course has always been to be able to pivot and change topics,” Goldie said. “I tell students at the start of the semester, ‘We have a syllabus, but we will be tracking global events and following the news … we’re going to talk about the problem that will most allow you to connect what you’re learning to what’s real in your life.’

“That’s the most effective learning environment that students can be in,” she added.

The History Department is having students keep “coronavirus diaries,” asking them to reflect on the semester before school closed, their move home, and Harvard life since then. The department will then submit many of the journals to the archive as primary sources. The project, organized by College Fellow Zachary Nowak, is up to 201 participants. A professor in the English department is running a similar project.

In the same department, the pandemic keeps cropping up in Michael McCormick’s graduate reading seminar. Part of the course looks at plagues that hit the Roman and Byzantine empires. They also looked at the Black Death in the Middle Ages. “Now that we are experiencing a pandemic ourselves, we are recognizing aspects of the experience that are documented in the eyewitness reports,” said McCormick. He is the Francis Goelet Professor of Medieval History and chair of the University-wide Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard.

Across the Charles River, Business School professors have written case studies on the economic fallout of the pandemic. Many professors and their guest speakers have also made the subject part of class discussions. A lecturer at Harvard Kennedy School had students help coordinate the schedules of 300 medical professionals at a local hospital. And at the Medical School students created a COVID-19 curriculum for physicians-in-training at Harvard and around the world.

Pulled from their traditional roles in the clinical setting, they asked themselves how they could best support those around them.

“One of the biggest challenges facing everyone right now is a lack of clarity about what is going on and what lies ahead,” said HMS student Michael Kochis, who worked on the project. “We saw a great opportunity to quickly collate and synthesize accurate information to share with those who do not have the resources to research it themselves.”