In the trenches

Three physicians in three distinct settings detail life in the midst of pandemic

One came out of clinical retirement to help. A second works in an emergency room at the center of the U.S. pandemic. A third treats low-income and immigrant communities outside of Boston. Judy Salerno, S.M. ’76, M.D. ’85, S.P.H. ’85, Tony Dajer ’78, and Mallika Marshall ’92 are among the thousands of medical professionals working nonstop to care for patients as the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the nation. The three physicians spoke recently with the Gazette about their experiences on the front lines of the crisis and the lessons the pandemic may teach.

Judy Salerno

Salerno came out of clinical retirement to help with the COVID-19 pandemic by liaising between medical providers and families of patients with the disease. She is the president of the New York Academy of Medicine.

GAZETTE: Where are you working right now?

SALERNO: I’m working at Bellevue Hospital, which is a large public hospital, a safety-net health care facility in New York City, because I felt that that’s one of the places that would have the greatest need and where I could have the most impact. I’m working with palliative care service, and we’re working very closely with the medical teams in the ICU, helping to be a liaison between the medical providers and the families for critically ill patients. The caseload has tripled on the service I’m working on. Nearly all the patients are COVID-intubated and critically ill. Because the families are unable to visit the patients, and because the ICU teams are so slammed with caring for patients, we’re trying to give medical updates to the families, trying to help families when there are very difficult decisions that have to be made about care and also to help families prepare when we think someone is not going to survive. We’re basically working with the sickest of the sick. It’s hard. It’s hard for the families; it’s hard for the medical staff; it’s hard for those of us who are working with both the families and with the staff. It’s stressful, but it’s meaningful.

GAZETTE: What prompted you to volunteer?

SALERNO: I live on the 27th floor of an apartment building and working from home all day long I heard the ambulance sirens — there are a number of hospitals not too far from my home — going day and night. It was making me feel more and more like I needed to step up. So when they started calling for retirees, I signed up immediately. I had concerns, and anybody who has been in contact with someone who has become sick from the virus has concerns, of course. I’m in my 60s, and I realize that I’m considered a high-risk demographic, but I really felt that I’m a healthy person; I have very few medical issues; and I’m pretty healthy. I’m a geriatrician by training. I’ve had lots of conversations with families over the years about issues in life-sustaining treatment, and I felt that this was something that I was particularly well-suited to do. So I said, you know, I have a skill set that is really needed by the overburdened health care system. So I signed up.

GAZETTE: What has the experience been like so far?

SALERNO: In my first full week at Bellevue there’s only one person I’ve seen who’s not been on a ventilator and critically ill. I’m not sitting down and having conversations with the patients. We’re rounding on the patients with the ICU teams, and then talking with the families. I can’t imagine how difficult it must be for them not to be able to see or hear their loved ones. It’s tough. It’s a tough situation. But I feel useful. Incredibly enough, most of the patients that I’m seeing are not very old. The idea that only older people will get very sick and die from this disease is not the case. We’re seeing numbers of people in their 40s and 50s and early 60s, who have other kinds of medical illnesses.

GAZETTE: Is there something different about this from your previous experiences?

SALERNO: There are no visitors allowed. Occasionally, there’s been a compassionate-care visit where one family member can go to say goodbye, but most of the patients are sedated and many of them on paralytic medications, so they’re not going to respond. When I ask families, “Is there anything I can do?,” most of the time the response is “Pray for my father” or “Hope for a miracle for my loved one.” That’s what I hear most from families: “We want a miracle.” Right now, to me, a miracle would be allowing a person to die with their loved ones around. I know everybody talks about closure, but this like a door slamming shut for families.

“We’re basically working with the sickest of the sick. It’s hard. It’s hard for the families; it’s hard for the medical staff; it’s hard for those of us who are working with both the families and with the staff.”

GAZETTE: When you began this work, was there something that came as a surprise?

SALERNO: The sheer volume of patients who were so incredibly sick was unexpected. Because we’re rounding with the intensive-care-unit teams, we’re seeing the sickest of the sick and the dying. One thing that surprised me is that some people have been at home doing OK for a week or so, and then their condition deteriorates very quickly. It’s very difficult for the family. I’m used to dealing with patients who might be older and have a long, progressively declining course, or patients with cancer. In those cases, there’s time for discussions with the family about what their wishes are. There’s no time for that, and so there’s no ability to really get a sense of what the person would have wanted for their care in this situation. The families are often saying, “Please do everything you can. He’s a fighter.” I’m hearing these kinds of things. In some situations, should their heart stop or something happen that requires resuscitation, they won’t make it.

GAZETTE: Can you speak to what the academy is doing in this moment?

SALERNO: The academy is committed to health equity, and through working with community-based organizations and the health care system from all sides, we are seeing that the most at-risk are the most vulnerable populations, and they are faring poorly. Everything we knew about the health inequities that we need to address I’m seeing from a personal point of view in the hospital now. All of the issues with disparities in health that I’ve been working on for all these years, I’m seeing in full display in the hospital units. I don’t think I’ve seen a patient in the past week who has not been a person of color.

GAZETTE: Do you have hope that this pandemic will change how we approach health care policy?

SALERNO: It has to change us. It has to. It’s changed everybody. I hope that there are lessons learned and that we can really think about what it means to be have health and well-being for everybody.

GAZETTE: You’ve got degrees in various fields. Do you think that background gives you any special insight or offers some advantage?

SALERNO: I have a unique perspective of having degrees in clinical medicine and public health. So, I was watching this [pandemic] unfold and thinking about all the public health aspects. Now, I’m thrown into the clinical, and I’m really grateful that I have an appreciation of the population-wide issue. I can explain to people why they need to stay at home in a very straightforward way. So I just want to make sure that I can message how important [physical distancing is] to smashing the curve, not just flattening it.

Tony Dajer

Dajer is an emergency-room doctor in New York City, where he has worked for 30 years. On Sept. 11, 2001, Dajer was the assistant director of what was then called N.Y.U. Downtown Hospital, the closest hospital to the World Trade Center.

GAZETTE: You’re in an emergency room at the center of the pandemic in the U.S. Can you tell us what that’s like right now?

DAJER: Early on what was very distinctive about New York was how blind we were flying, how restrictive testing was initially. We all suspected that it was about to hit New York in early March, but we really had very little idea of what we were about to deal with, even though we all had a lot of anxiety about it. In the first 10 days, every day was another ratcheting up of the acuity and the severity of what we were seeing: the patients who would be decompensating quickly, the colleagues who were getting sick, and how suddenly scary it was — we weren’t clear what the threat to ourselves was. We were advised to use protective gear, but we weren’t sure how much we needed and whether it was working. Right now it is certainly anxiety-provoking. It is more an enemy that you’ve recognized, one you now have the measure of, as opposed to this complete blindness we had at first.

GAZETTE: Is there some particular problem area that you see?

DAJER: What’s very unique about the U.S. and our situation is our lack of testing. Testing is still a difficult proposition, even in research institutions in New York City. It’s not on-demand; you still have to meet certain criteria, which at the moment are appropriate given the supply. Until we get even the basics of population testing, this will be out of control, or not only out of control, but will recur in ways that we don’t predict; hotspots will keep cropping up. And I think that that’s a difficult concept to convey, even though there’s a lot of pressure to say that testing is adequate. Now, it definitely is not [adequate], even today.

GAZETTE: We hear a lot about COVID-19 on the news all the time. Are there things you see that we wouldn’t necessarily know about? Is there a story that’s not being told?

DAJER: Though it has been hinted at in some reports, the negative untold story is how many deaths are happening without being tallied — the true total of the epidemic. We all see it every day. The paramedics, the medics, the ambulances go out to households, and there’s a patient in cardiac arrest. Those deaths are not tallied. If you don’t have a positive test or are not assessed in the hospital, you don’t make the “official count,” which is sort of mind-boggling, but that’s where we are right now. In a few months, if we go back and look at our mortality rates during this period compared to a year ago, I think we’re going to be fairly shocked at how deeply destructive this epidemic was, even more than we imagined.

GAZETTE: What are you seeing that inspires you, keeps you going?

DAJER: On the front lines, what’s deeply impressive are the nurses. They’re the ones who spend the most time with patients and are the most heroic by far. So are the paramedics and emergency medical technicians who were taking patients from households that probably have six family members infected with COVID. They are exposing themselves to very high chances of catching it themselves. I’m certainly scared, but I’m not nearly as exposed as those folks are. The housekeepers and environmental folks who clean patients’ rooms are at a super-high risk and are really the unsung heroes. The other heartening part is how quickly clinical folks learn, how we’re sharing information on an hourly basis, how rapidly escalating our understanding of the disease is. Certainly that was helped by the Italians sharing information as they were dealing with their crisis. It’s very much an all-hands-on-deck situation where surprising amounts of capacity are being created with the folks at hand. Those in cardiology practices, whose most important practice is outpatient cardiology, are now being redeployed as ICU doctors. They are opening full intensive-care units with doctors who have not been in one for years but have the skills that they can immediately rapidly ramp up again.

“The enormity of what’s happening right now is so great that no one’s going to come out of this feeling like a hero.”

GAZETTE: You’ve had a range of experiences in emergency care over your career. You were in what was then called N.Y.U. Downtown Hospital, the closest hospital to the World Trade Center in September 2001, for instance. Do you think your past experiences helped prepared you for this?

DAJER: I learned from that experience that clear leadership and full transparency are really critical. When you’re in a knowledge deficit — with a new phenomenon, things changing very rapidly — knowing who’s in charge and being able to trust that authority as being knowledgeable, that is really critical. I think we’ve done a pretty good job of that. But it’s also finding new ways to support each other.

GAZETTE: Are there any other comparisons that come to mind?

DAJER: One thing that I found very difficult after 9/11 was how fast and impersonal it was, that even though you obviously were dealing with very intense moments with patients, you didn’t get to know them well. This particular disaster [the COVID-19 pandemic] is going to be very difficult because of the impersonality of it: Patients are being forced to be isolated; we’re not really comfortable getting near them for too long; we’re not getting to know them; and the sickest patients are on ventilators and can’t talk to you. So there’s a lot of emotional distancing that will be difficult afterwards. Since 9/11, I have stayed in touch over all these years with the widow of a patient who unfortunately died a few months after 9/11. Yesterday, she sent me an email just wondering how I was doing. That kind of emotional connection to your patients, as well as obviously your colleagues, it’s a tough thing to maintain. But you really need to figure out a way to explore it. Right now, we doctors have a support group, where we do a Zoom meeting once a week where we just share experiences and catch each other up on how we’re dealing with this — from a clinical pearls standpoint and also from an emotional [standpoint]. For example, “How do you make sure you’re safe? How do you coordinate your teams?” Just how you’re feeling.

GAZETTE: Are you anticipating any particular emotional fallout for medical workers?

DAJER: It is surprising that people feel that they haven’t accomplished anything at the end. The enormity of what’s happening right now is so great that no one’s going to come out of this feeling like a hero. The ICU folks are going to feel like they lost too many patients. The ER people are going to feel like they didn’t intubate patients in time or that they missed a few signals, or that they didn’t save more lives. It’s a very pervasive and corroding thing. In the weeks after 9/11, even people who were in the thick of it doing heroic work, they were all saying to me exactly the same thing: They felt they hadn’t done enough. It’s the human condition: When we’re witnessing something terrible, you somehow think it’s your fault.

GAZETTE: Are you in touch with any of your former classmates during this tough time?

DAJER: My three freshmen roommates have been incredibly supportive. Two of them are also doctors, though not ER doctors. We are emailing or talking every couple of days. It is a nice feeling of solidarity, knowing that people with great integrity and commitment are on the frontlines in other areas as well. It is a nice feeling that we’re all still working toward that better world that we all were trained for.

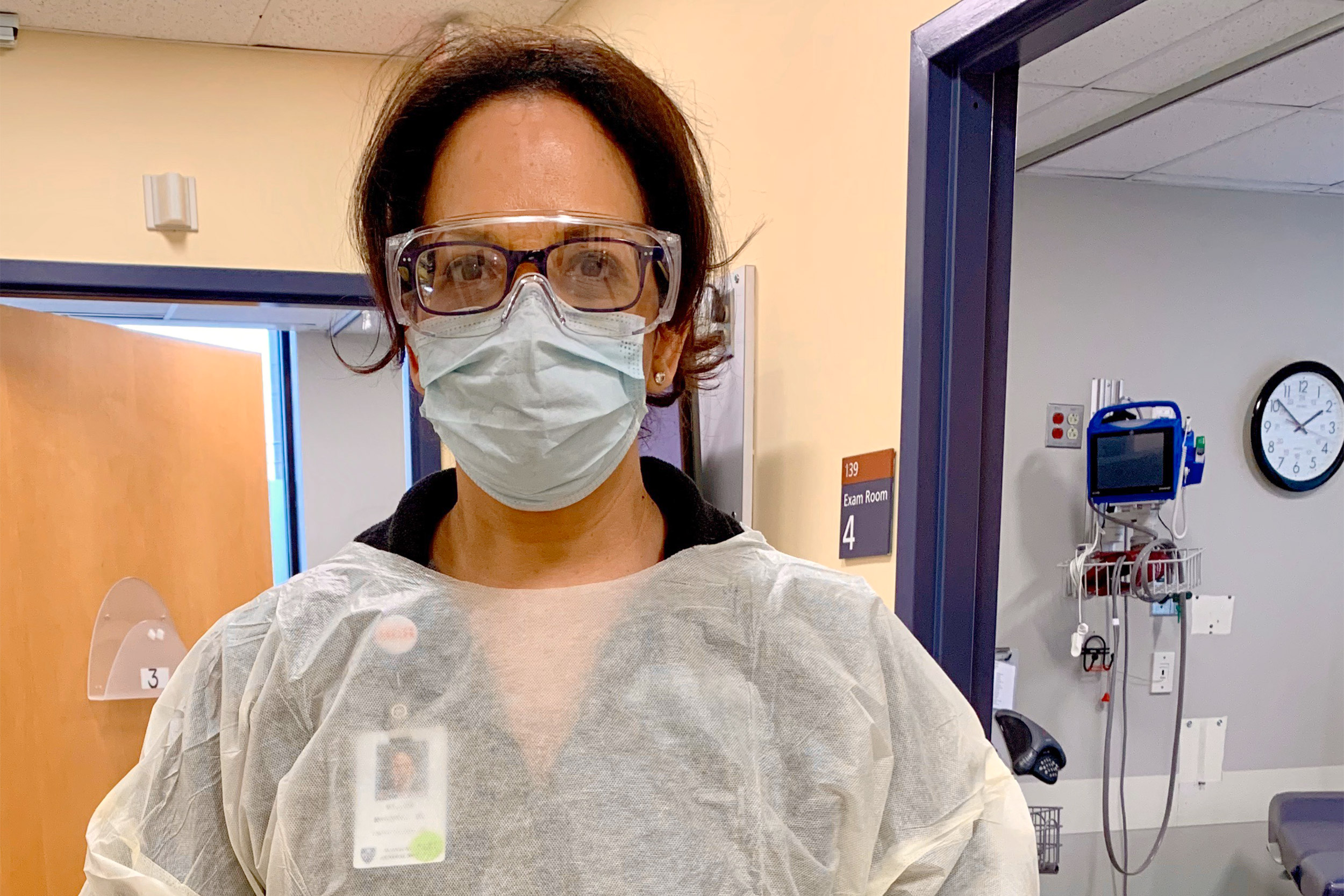

Mallika Marshall

Marshall is a Harvard Medical School instructor, a Mass. General staff physician, and an urgent-care physician who has spent 20 years at the MGH Chelsea Health Center in Massachusetts, where she works with low-income and immigrant communities. Marshall is also an Emmy Award-winning health reporter at CBS Boston/WBZ-TV.

GAZETTE: Can you say a little about the community you serve?

MARSHALL: Chelsea is a low-income, working-class community. We have a lot of immigrants from the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and many other countries. It’s only about two square miles, but it’s densely packed with more than 40,000 residents, so a lot of residents living on top of one another. I work in the urgent care department, so we treat anyone who walks in the door, the “walking wounded.” There are a lot of newly arrived immigrants, many of them are undocumented. Because we’ve been here for so long, the Health Center has developed trust in the community — that you are safe here, that we’re not reporting anyone. That has been a benefit, especially in this pandemic, because if we had not built that trust for many years, we might not be seeing the numbers of patients there that we have been. A lot of the residents of Chelsea are essential workers. I had a middle-aged woman who had had fevers for a week. I asked her what she did for a living; she worked in produce. I said, “When did you last go to work?” She said, “Yesterday.” I asked her why she had been working for a week with fevers. She said, “I had no other choice.” That’s the answer for a lot of people. They have families to feed. They are still employed, luckily, and they feel like they just need to sort of soldier on. I had a [COVID patient] who had a fever and body aches, and I asked him who he lived with. He said, “I’m living in my car.” “I said, ‘Do you have a family?’” He said there were about six of them in a studio apartment, and so he was out, living in his car, trying to hustle for work, and trying to avoid infecting his family.

GAZETTE: Do most of your patients get regular medical attention?

MARSHALL: Not all of our patients have primary care physicians, which many of us are fortunate to have, and they often have unreliable contact information. We’ve been trying to reach an elderly woman who had tested positive. We never could reach her or any family members, so we can only hope that she’s doing OK. And then a lot of people don’t have insurance, which makes them less likely to seek care. Recently, I had a woman who was very sick with COVID symptoms, and she needed to go to the emergency room. We were going to send her by ambulance, and she said she just couldn’t do that. The last time they had sent her by ambulance, she got a $3,000 bill in the mail for the ambulance transfer, and they just could not afford to pay that. So she signed out against medical advice, promising that her husband would take her immediately to the ER, and I have to trust that she did get there.

GAZETTE: What are the unique challenges you’re seeing?

“I’m hoping that we don’t forget it, that we can learn some important lessons about social determinants of health. … [To] really try to get at why — and try to fix it. This might be the prime opportunity to do that.”

MARSHALL: Over the past 10 days, the numbers have definitely exploded. And Chelsea is definitely a hotspot here in the state. According to The Boston Globe just a couple of days ago, they actually tested 200 Chelsea residents randomly with antibody blood tests, and they found that about a third of people tested positive. Many of them had never had any symptoms, which just kind of gives us an idea of how widespread the infection is in Chelsea. Fortunately, Mass. General has taken good care of us, and we’ve got good protective gear, all the things that we hear that so many other hospitals are lacking. [I hear] about people wearing garbage bags — I can’t even imagine. But working a 12-hour shift yesterday, you know, it’s tough. I remember a Code Blue was called — a COVID patient who was having problems breathing. I had to get upstairs, but I couldn’t get the elevator, and I had to run up the stairs. By the time I got to the patient — with my mask and my gloves and my shield and gown on — I was so out of breath. I could barely get a sentence out, but in between breaths I tried to say, “Ma’am, how is your breathing?” I’m sure it didn’t instill any confidence in her that I was going be able to save her. I couldn’t even speak! But we are lucky, and we get through the day. Sure, we’re tired, but we feel like at least we’ve done our part.

GAZETTE: As a doctor and a health reporter at CBS Boston/WBZ-TV, what do you think of how the media is covering this health crisis?

MARSHALL: In the past week or so I have received multiple messages from viewers saying that they wish they could hear more positive news, and we need to continue to do that and do more of that. The pandemic has also exposed the racial and ethnic disparities in our health care system, with an abundance of coverage on that over the past couple of weeks. But I’m hoping that we don’t forget it, that we can learn some important lessons about social determinants of health. Not just report that black and brown people are dying in greater proportions, but also really try to get at why — and try to fix it. This might be the prime opportunity to do that.

GAZETTE: You were a part of a virtual townhall called “Race and the Pandemic: On the Front Lines,” organized by the Coalition for a Diverse Harvard and a number of other alumni groups. Did it offer you any new insights?

MARSHALL: We had such a good discussion about the experiences of people of color, from my experience in Chelsea to the Asian community down in New York City, and this unbelievable story about the Navajo Nation and their unique struggles. And I know that people are craving more, so hopefully we can do some more discussions like that through the Harvard alumni groups.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.