A faithful keeper of time

Richard Ketchen tends to and maintains Harvard’s clocks.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

For the past 30 years, Richard Ketchen has cared for and repaired some of Harvard’s oldest and most historic clocks

The clock is older than the nation itself but still keeps time down to the minute — those in meetings at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) offices, in fact, often rely on its chime to mark the beginning or end of the gathering. At least, that’s the way it was.

In January, the 8-foot-tall longcase clock, built in London around 1750, started running a few ticks slow, which became a minute, then almost two. The tension on the strings had suddenly become tight when winding it. It was enough to concern the clock’s onsite monitor, Ann Hall, GSAS director of communications. She contacted the Harvard Art Museums, which loans out this clock and hundreds like it throughout campus.

Enter Richard Ketchen, one of the faithful keepers of Harvard’s antique clocks.

“I come when I’m called,” said Ketchen, an expert in the measurement of time. He is the Harvard Art Museums and other institutions’ go-to horologist. He comes in to maintain, fix, and restore timepieces that are too old or complex to be trusted to anyone else. (Speaking of not trusting anyone else, remember that daylight saving time begins at 2 a.m. Sunday, and you’ll need to set your clocks an hour ahead.)

“He’s a real skilled clock engineer,” said Sara Schechner, the David P. Wheatland Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. “There are very few people like him in the country … It’s a skillset that is going away.”

Ketchen has been tending to many of the University’s antique timepieces as an independent contractor since he helped restore some for a symposium on longitude in the 1990s. Along with the museums and the collection, Ketchen also works with other organizations and Schools across campus that have historic clocks in their possession.

“Sometimes it’s just taking the clock and oiling it and adjusting it and tuning it up a little bit,” Ketchen said. “Other times the clock is either so far gone or people want to do the right thing, so I will take it completely apart and clean everything, adjust everything, make missing parts, make parts that are there but incorrect, and make it pretty much as it left the maker’s hand.”

The work is meticulous and daunting, involving as it does a complex system of gears, wheels, plates, axels, weights, bells, and more. “There’s a whole lot to remember, a whole lot do, but if you’ve done a lot of these … and if you’ve been doing this as long as I have then that becomes easy,” Ketchen said.

Ketchen, who earned a certificate in machine shop practice and mechanical design from Wentworth Institute in 1966, started working on clocks 51 years ago as a side hustle. “It was serendipitous,” he said. “I had just gotten out of the Army. I got a job, but I was looking for a hobby. The first time I looked inside a clock I said, ‘Whoa, I can fix that.’ And I did, and I got paid for it. I said, ‘Wow, how long has this been going on?’ And then I found that there was a lot more to it than what I thought, and it was wonderful.”

Ketchen has been a fellow of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors and won a craftsmanship award from the association in 1980. He has also served as president of the Boston Watch and Clock Collectors. He started working full time restoring clocks in 1990 when he lost his job as an engineer

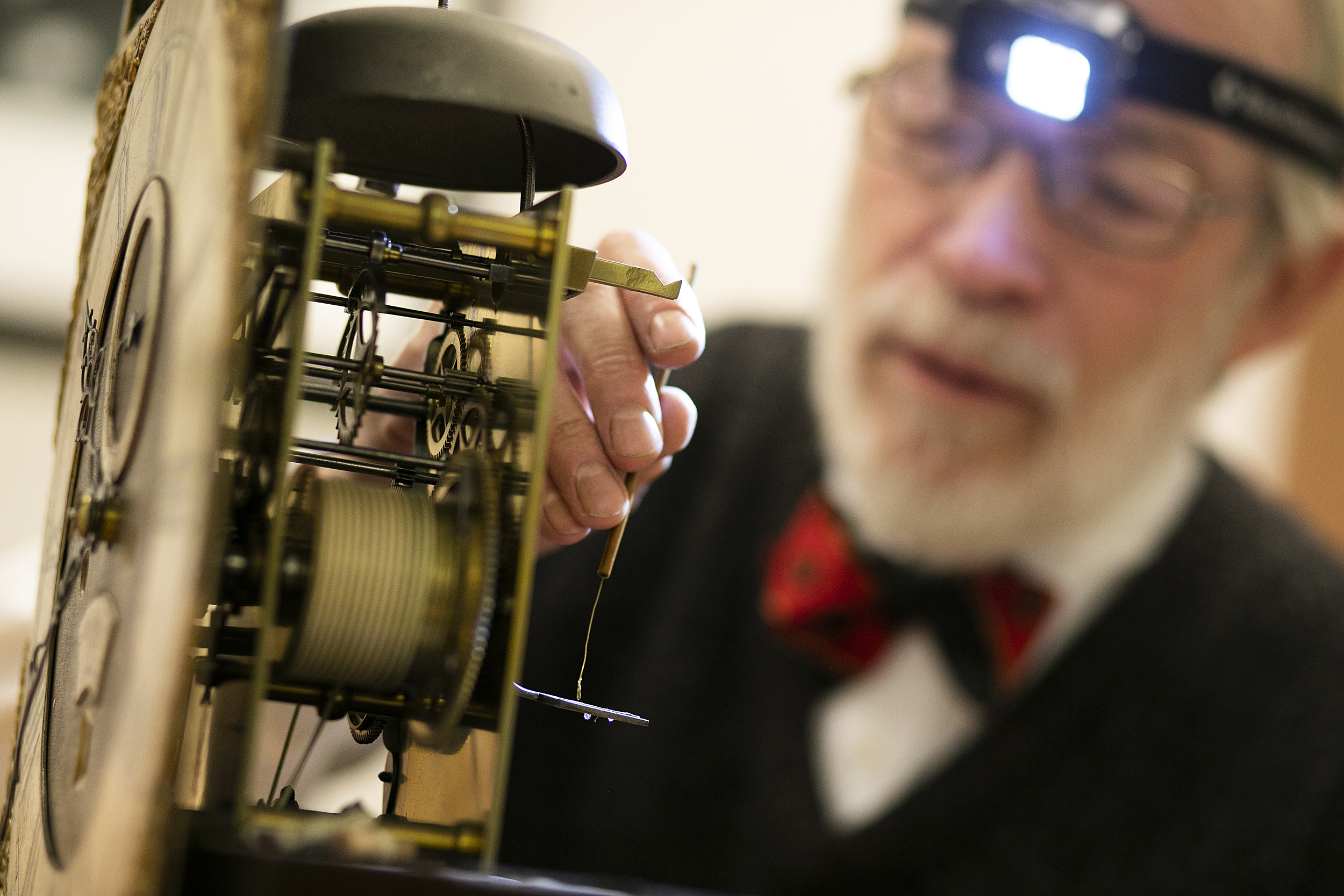

For his work on Harvard’s clocks, which number more than 200, Ketchen is called when needed. At the Harvard Business School last fall, he took the top off a Simon Willard clock made in the last part of the 18th century and, wearing a flashlight headband and using a thin metallic wire, oiled its gears and checked the cords to make sure they weren’t close to snapping and sending the weights they hold crashing down. Simon Willard was Harvard College’s official keeper of clocks from the 1770s to 1829.

In August of last year, Ketchen spent half a day at Lowell House working on an especially complicated American tall case from the early 20th century. He helped restore its music system, which plays one of four sequences of the Westminster Abbey melody on its chimes depending on the time and counts the hour on the gongs. Ketchen swapped out the hammer leathers which act as dampers for the chimes and gongs, installed new hammer strings to keep the hammers from going too far back, and added new chime chords. He also lubricated the clock and used a meter to adjust it to the proper beats per minute. While he was there he even pulled down a clock off the mantel, an heirloom belonging to former House Dean Dorothy Austin, and tinkered with it at no charge.

Just a few weeks before he was beckoned to the Smith Campus Center to work on the clock at the GSAS office, Ketchen had a timepiece from the Harvard Medical School (HMS) taken apart in his basement in a suburb northwest of Boston, where he takes clocks in need of more extensive care or restoration. There he has all the tools he needs to make custom parts if needed. For the Medical School’s clock, which was built around 1790, he crafted a new winding crank.

“Pieces really have to be appropriate to the clock,” Ketchen said. “You can’t just take a pendulum or a hand from one era or one part of the world and put it onto a clock that came from another era or another part of the world. It has to be consistent with the style of the clock.”

It’s why Ketchen, as he did with the HMS clock when he first worked on it in 2001, makes rubbings and sketches of certain pieces of the clocks he works on. He has hundreds of these and keeps them in a notebook.

“Oftentimes, I will find a clock where the hand is missing, or it’s inappropriate,” he said. “Then I can go back through these rubbings and find what the correct hand should look like [and then make it].”

Ketchem uses a variety of intricate tools to fix timepieces, even small ones.

A lot of Ketchen’s knowledge comes from books, but at this point in his career, the self-taught horologist has essentially become a walking encyclopedia on the subject.

“Richard is amazing,” said Steven Mikulka, the preparator in Collections Management at the museums who is Ketchen’s main contact and works closely with him when he is on campus. “He’s so experienced — he’s built his own clocks — that he can look at a clock and figure out the gear train and figure out the mechanics of it in literally seconds.”

Take the clock on display in a gallery at the Fogg Museum. He hadn’t seen it since he took it apart in his workshop in 1993, but looking at the tall Dutch timepiece made sometime between 1750 and 1775 by one of the leading clockmakers in 18th-century Amsterdam, Otto van Meurs, it all came back to him.

The music is what makes it special. To mark the hour its 10 carillon bells powered by an internal gear train plays one of eight tunes, and its case, inlaid with woods from all around the world, was meticulously fit together like a jigsaw piece because that’s how it was done at the time.

“The clock also has an interesting feature,” Ketchen said. “Being a Dutch clock, it has what is called Dutch striking. So, on the hour, it will strike the hour that the hand is pointing to. On the half-hour, it will strike the next hour coming, and it will do that on a different bell. … It’s got something to do with the way their language is formatted. They don’t say half past the hour, they say half till the hour — sort of how we say quarter of.”

With Mikulka’s help, Ketchen took the mahogany and pine top off the GSAS timepiece and deftly went about removing the weights, pendulum, and dial. He then brought the dial and the movement mechanism attached to it to a nearby room where he placed the mechanism on a wooden mount — which he crafted years ago to hold pieces like this. He began to oil it while doing a quick inspection.

“What I’m looking at are the pivots that come through the plates and all these axles that all the wheels are attached to,” he explained. “What I’m looking for is to see if there’s any red rust, which … is an abrasive, and we don’t want an abrasive in the clocks.”

Another thing he looks for are names. On the dial is often the name of the maker or the dealer who sold the clock. Other names he finds are those of horologists who’ve serviced the clock. On this one, he found the name Charles Ditmas, who marked it in 1960 and 1970. Ditmas, who passed away in 2002, was Harvard’s honorary clock keeper from the 1940s to sometime in the early 1990s.

After finishing, Ketchen and Mikulka reassembled the clock, now running smoothly and back on time. Hall told them how everyone in the office cherishes the clock (a few had even walked by and told Ketchen and Mikulka themselves).

Ketchen smiled. “It’s nice to work on nice clocks and work on them for people who like them,” he reflected, then went on to his next appointment.