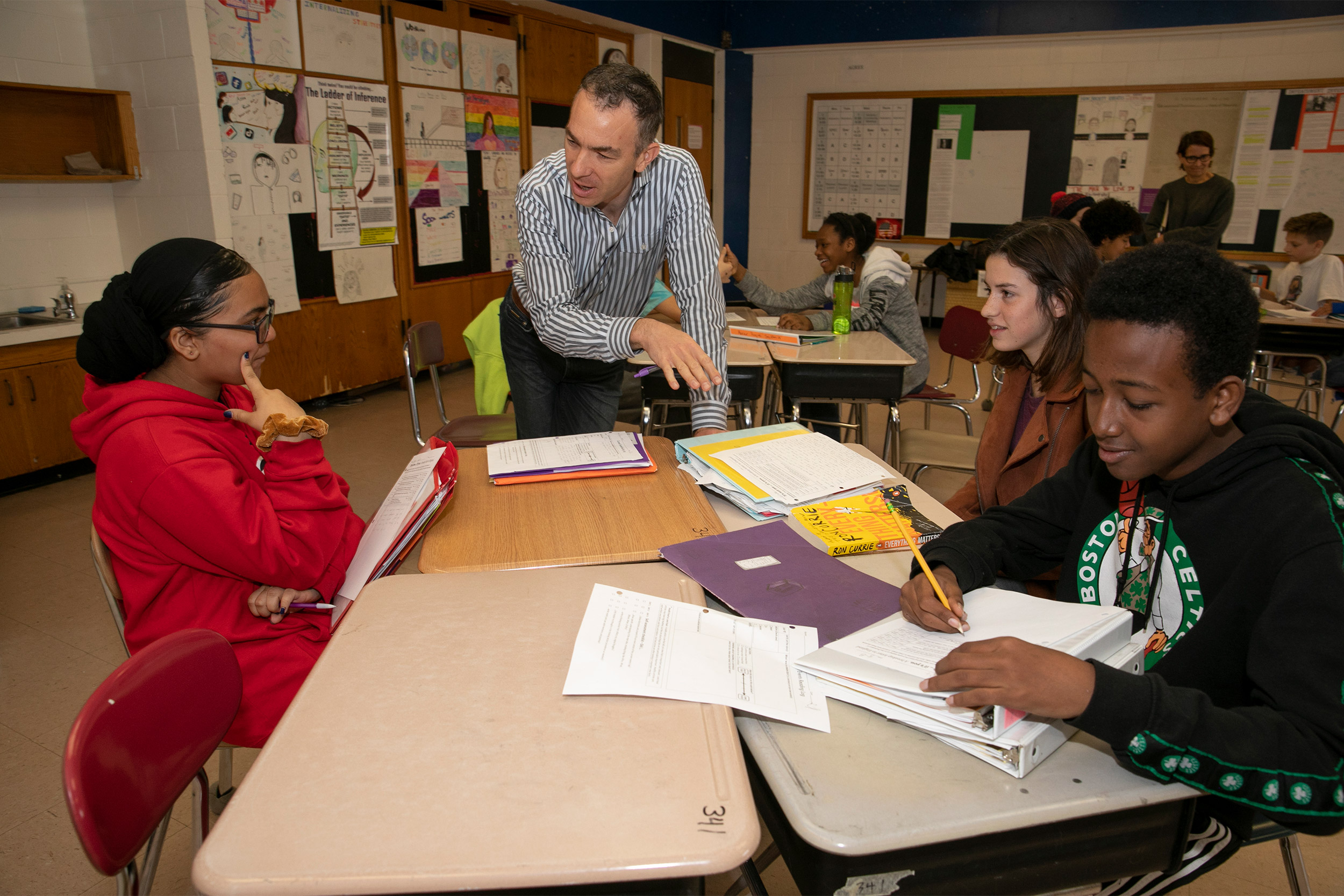

Students at Vassal Lane Upper School use the game “Portrait of a Tyrant” as part of the new civics education curriculum.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Reframing civics education

Democratic Knowledge Project bridges core knowledge and diverse perspectives in statewide pilot of interactive curriculum

Vassal Lane Upper School eighth-grader Bodie Morein toggled his laptop mouse, marching Brianna Little, his video game heroine, to a fort in New York state during revolutionary times. A crowd formed, chanting:

“If I say, ‘This is our,’ you say ‘Petition!’ “

“If I say ‘Stamp Act,’ you say ‘No consent!’ ”

The game, “Portrait of a Tyrant,” is a small part of a year-long civics education curriculum with high stakes — the future of civics knowledge, identity, and engagement — for Morein’s class and students across the state.

“We are working from a critical data point that found 70 percent of Americans born before World War II considered it essential to live in a democracy. For today’s millennials, it’s less than 30 percent,” said Danielle Allen, principal investigator for the Democratic Knowledge Project (DKP) at Harvard. “Our vision in doing this work is trying to rebuild a supermajority, to get that number over 66 percent.”

The project evolved from Allen’s research work, including the Declaration Resources Project and Ten Questions for Young Changemakers framework, which she brought with her to Harvard in 2015. Urgency for a comprehensive curriculum came from a state-mandated education reform signed into Massachusetts law in 2018. Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor and director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, said, “I have had a lab for a decade with the stated purpose to identify and disseminate the bodies of knowledge, skills, and capacities citizens need to build and maintain thriving democracies. So when the policy conversation started, we had built de facto content. We had been a one-off resource creator. But we saw teachers struggling with how to take all these pieces and parts and turn them into a yearlong curriculum, and knew we could be part of the solution.”

The project found a partner in the Cambridge Public Schools with which to collaborate on creating and implementing the curriculum. According to Jenny Chung, K-8 District social studies coach for Cambridge, “Teachers were at the center from the beginning. The collaboration was so successful because the entire eighth-grade team was at the table with the project throughout the curriculum conversations. We mapped out the arc and essential questions together, then individual teachers piloted different parts of the curriculum. Change can be difficult, and our teachers feel invested and ready to tackle the bumpiness that is any new curriculum.”

Chung said the thematic and agency-centered curriculum provided a break from traditional teaching approaches. “Rather than marching through events and documents chronologically, DKP’s framework helps students engage with the past, present, and future planning in meaningful ways,” she said.

This was clear on an afternoon in Bill Folman’s class at Vassal Lane, as students like Morein played “Portrait of a Tyrant,” which the project is developing with the educational videogame production company Amplify. The game has six episodes, which are based on grievances against King George that the colonists detailed in the Declaration of Independence. The episodes give context and modern relevance to the Declaration of Independence, and are tied to the Cambridge schools’ curriculum. In the game, Brianna encounters protests, a ship-burning, and an illicit meeting that ends in a tar and feathering. The sepia-toned coloration matches copies of primary documents, like replicas of Phyllis Wheatley poems and articles from newspapers (Virginia Gazette, Georgia Gazette) of the period.

“I like all of the dialogue and the art is really cool,” said Morein.

“You need to make more decisions than in other games,” said classmate Dawit Gebresellassie.

On the whiteboard at the front of Folman’s classroom, students from previous sections had written hacks to help their fellow students: “Put the letter in the shoe,” one suggested. “Don’t throw the shoe at the mansion,” read another, referencing a character’s decision to participate in an impending riot. Folman walked around with his own game in hand, asking students to share what was going well, and where they might be finding kinks.

“The goal is to have students engage with the content and make choices and give context in a way that is, hopefully, fun,” said Folman, who was part of the Cambridge schools team that worked with Allen’s group. “One of the things I like about this curriculum is that it lends itself well to integrating current events, and current events are super-important. If our ultimate goal is to make better citizens, good citizens need to be aware of what’s happening in their world. But so often it’s hard for middle schoolers to understand the news — particularly political news. By focusing on the workings of government early in the year, a lot of these news stories start to make sense. It’s hard to become good news consumers if students are avoiding topics because they are confusing to them.”

“Portrait of a Tyrant” is part of the teaching unit titled “How to Write a Constitution,” which followed an introductory unit on identity, values, and agency, and preceded “Loyalty, Voice, and Exit: The Philosophical Foundations of Democracy,” which the students are studying this month. Later, the students will focus on the levers of change in government, and finally create a civic action plan about something they feel passionate about.

“None of this would have worked if we hadn’t formed this partnership. We have massive amount of content, but we do not have instructional expertise for eighth-graders and they do. It was a beautiful marriage of expertise,” said Allen. She is piloting the DKP-Cambridge Grade 8 curriculum with 15 teachers and 1,000 eighth-graders in eight districts across the state.

Allen called the shift from textbooks to an open-source, online curriculum with multimedia resources like the video game the “scariest” part of the curriculum for teachers. “They have to let go of control on the days kids are playing. Shifting control is part of the curriculum, and that’s a big shift,” she said.

DKP is supported by Massachusetts grants from the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.