Photo illustration by Ian Cuming

House of cards

Since last recession, a surge in wealthier families opting to rent instead of buy is driving up the market, making affordable housing scarcer, study finds

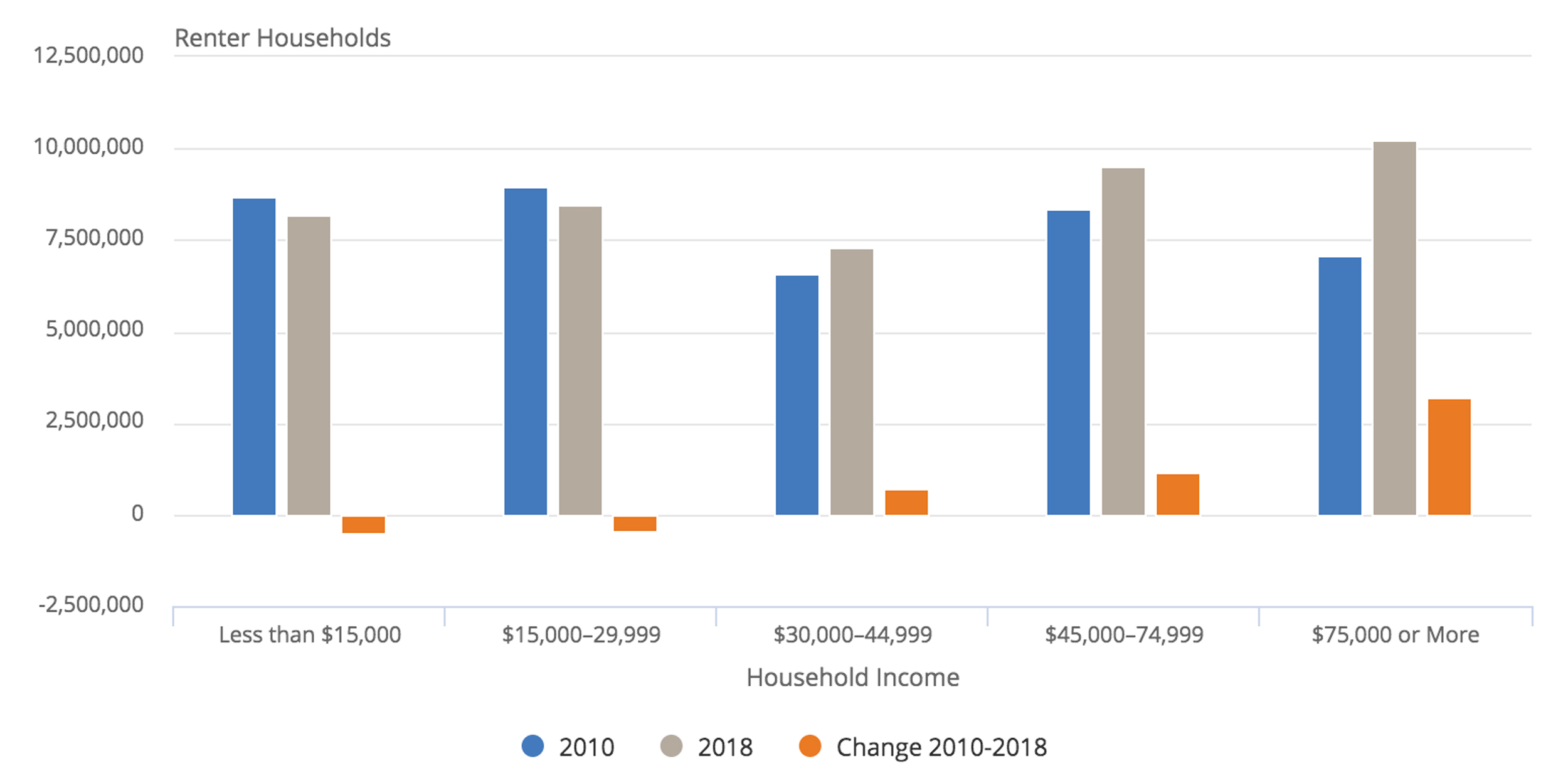

With higher-income households driving much of the growth in rental demand since 2010, the new housing supply has been concentrated at the upper end of the market, squeezing middle-income Americans, according to a report released today from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Households with incomes of $75,000 and higher accounted for more than three quarters of the growth in renters, 3.2 million, from 2010 to 2018, the report says. The rising demand and constricted supply have reduced the stock of low- and moderate-cost rental units.

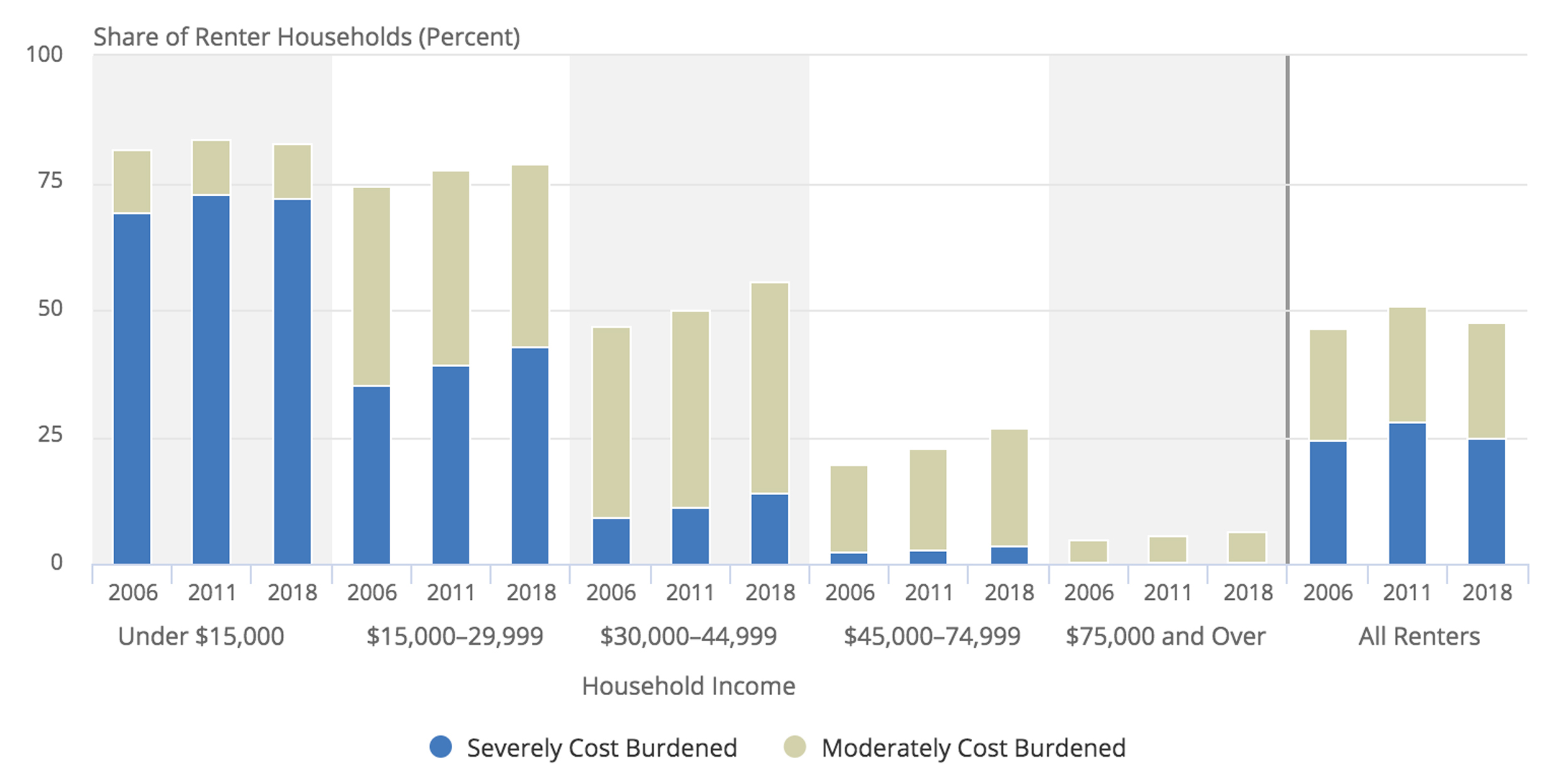

The shift has significantly altered the profile of the typical renter household. Nationwide, a growing number of renters with incomes between $30,000 and $75,000 are now paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing.

“Despite the strong economy, the number and share of renters burdened by housing costs rose last year after a couple of years of modest improvement,” said Chris Herbert, managing director of the center. “And while the poorest households are most likely to face this challenge, renters earning decent income have driven this recent deterioration in affordability.”

Alarmingly, a majority of lowest-income renters spend more than half of their monthly income on housing, conditions that have led to increases in homelessness, particularly in high-cost states.

Further constraining the market, renting has become more common among those traditionally more likely to own their homes, including those aged 35-64, older adults, and married couples with children. Families with children now make up a larger share of renter households, 29 percent, than owner households, at 26 percent.

“Rising rents are making it increasingly difficult for households to save for a down payment and become homeowners,” said Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, a research associate at the center and lead author of the report. “Young, college-educated households with high incomes are really driving current rental demand.”

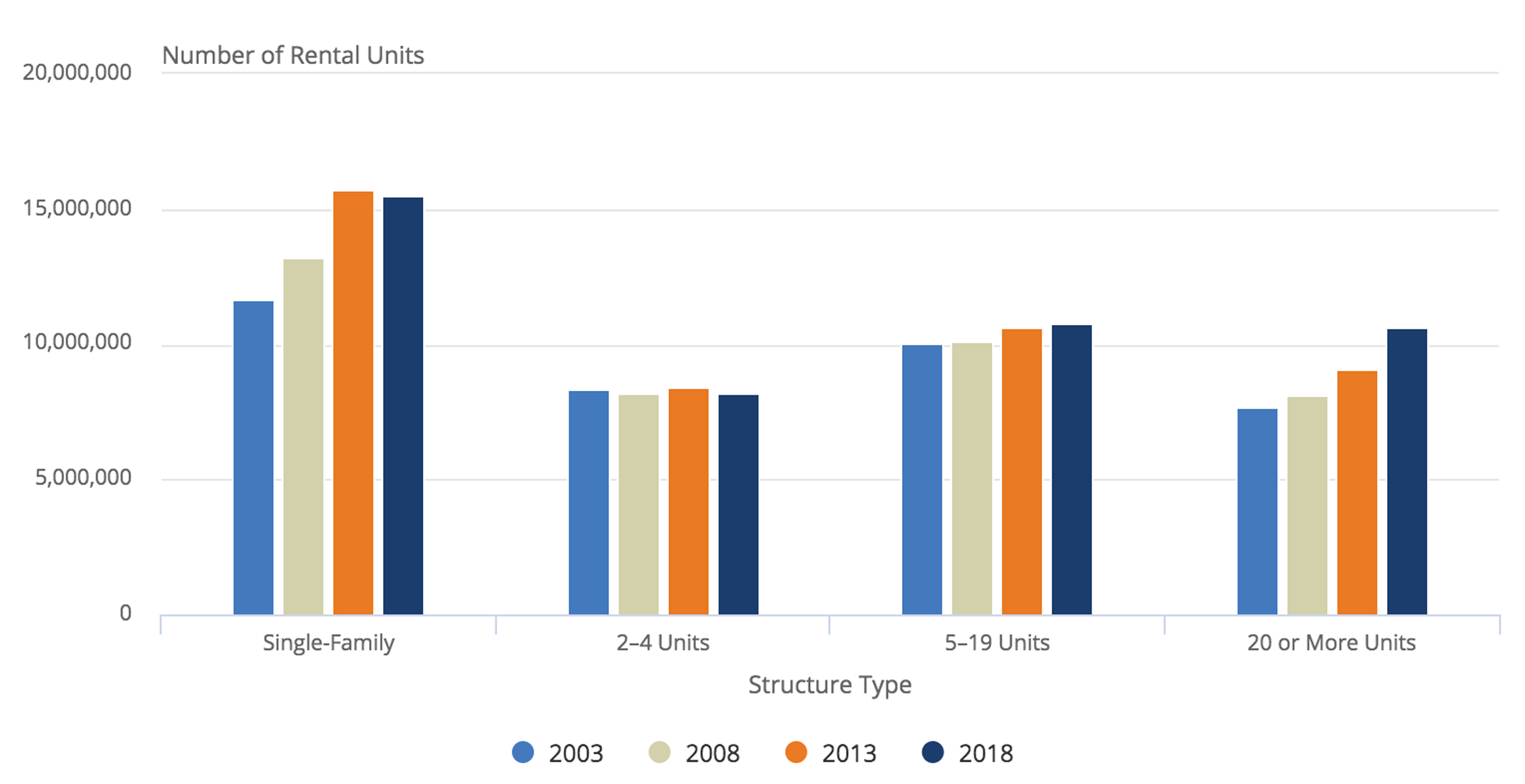

New rental construction remains near the highest levels in three decades, with a growing share in larger buildings intended for the high end of the market. The share of newly completed apartments in structures with 50 or more units increased steadily from 11 percent in the 1990s to 27 percent in the 2000s to 61 percent in 2018.

The unprecedented growth in demand from higher-income renters clearly contributed to this shift, although the rising costs of housing development are also a key factor — particularly the soaring price of commercial land, which doubled between 2012 and mid-2019.

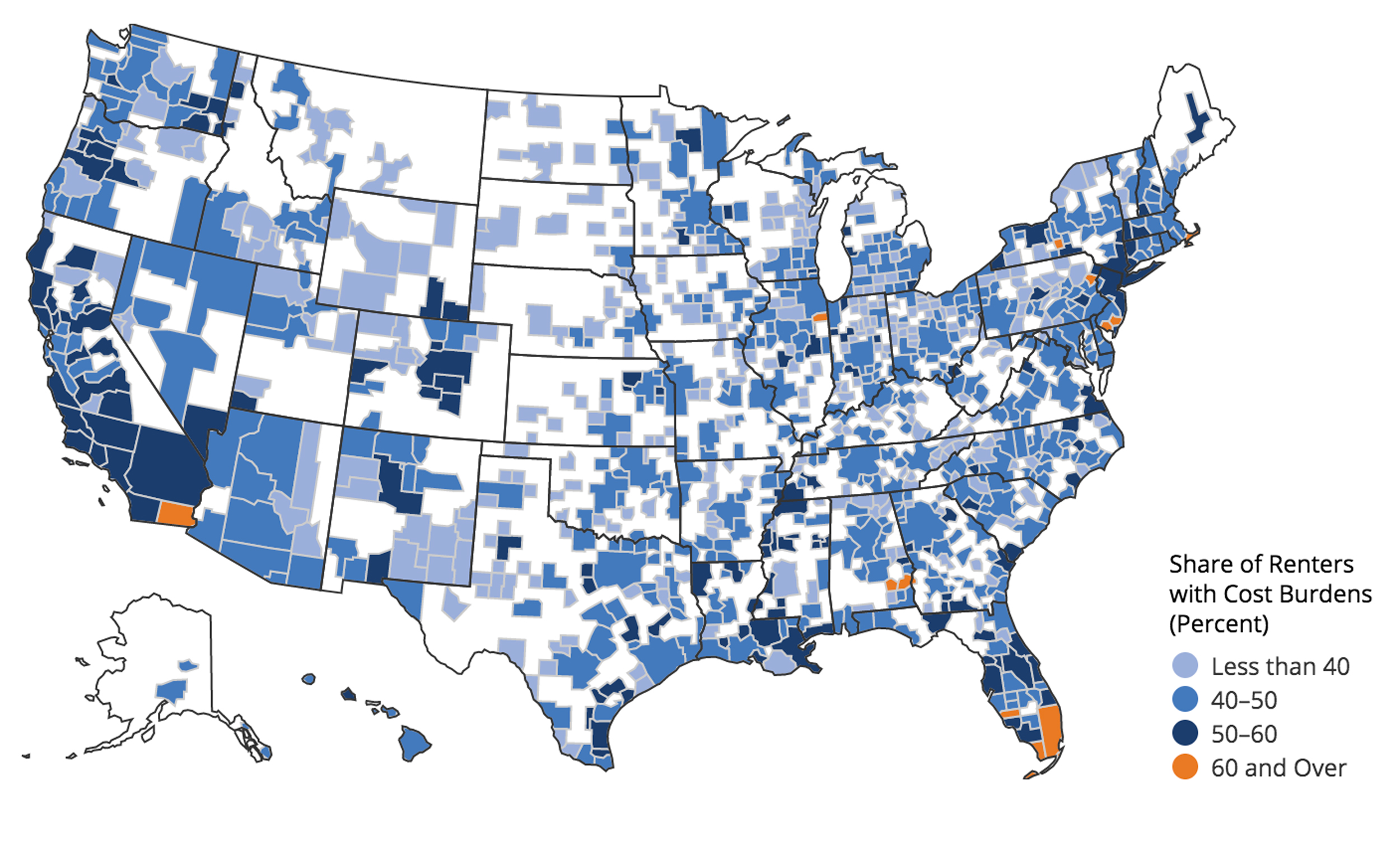

As the national vacancy rate edged down in 2018 to its lowest level since the mid-1980s, rent gains continued to outrun general inflation. The Consumer Price Index for primary residence rental costs was up 3.7 percent year-over-year in the third quarter of last year, far outpacing the 1.1 percent increase in prices for all non-housing items. Additionally, apartment rental prices rose to new heights, up 150 percent between 2010 and the third quarter of 2019.

Climate change also poses a threat to the stability of American renter households. According to the report, 10.5 million of the country’s 43.7 million renter households live in zip codes that incurred at least $1 million in home and business losses due to natural disasters between 2008 and 2018. Moreover, 8.1 million renter households report that they do not have the financial resources to evacuate their homes if and when a disaster strikes.

Local governments increasingly have found themselves on the front lines of the rental affordability crisis. In response, many jurisdictions have adopted a variety of promising strategies to expand the supply of affordable homes and apartments, including increased funding as well as zoning and land-use regulation reform to allow more higher-density construction.

“Last year, Minneapolis became the first large American city to end single-family zoning,” Herbert said. “This has the potential to greatly expand the rental supply and improve affordability in that city. But, ultimately, only the federal government has the scope and resources to provide housing assistance at a scale appropriate to need across the country.”