Backbone of success

iStock

In a first, researchers unveil stem cell models of human spine development

More than 20 years ago, the lab of developmental biologist Olivier Pourquié discovered a sort of cellular clock in chicken embryos where each “tick” stimulates the formation of a structure called a somite that ultimately becomes a vertebra.

In the ensuing years, Pourquié and others further illuminated the mechanics of this so-called segmentation clock across many organisms, including creation of the first models of the clock in a lab dish using mouse cells.

While the work has improved knowledge of normal and abnormal spine development, no one has been able to confirm whether the clock exists in humans — until now.

Pourquié led one of two teams that have now created the first lab-dish models of the segmentation clock that use stem cells derived from adult human tissue.

The achievements not only provide the first evidence that the segmentation clock ticks in humans but also give the scientific community the first in vitro system enabling the study of very early spine development in humans.

“We know virtually nothing about human development of somites, which form between the third and fourth week after fertilization, before most people know they’re pregnant,” said Pourquié, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School and a principal faculty member of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. “Our system should be a powerful one to study the underlying regulation of the segmentation clock.”

“Our innovative experimental system now allows us to compare mouse and human development side by side,” said Margarete Diaz-Cuadros, a graduate student in the Pourquié lab and co-first author of the HMS-led paper, published Jan. 8 in Nature. “I am excited to unravel what makes human development unique.”

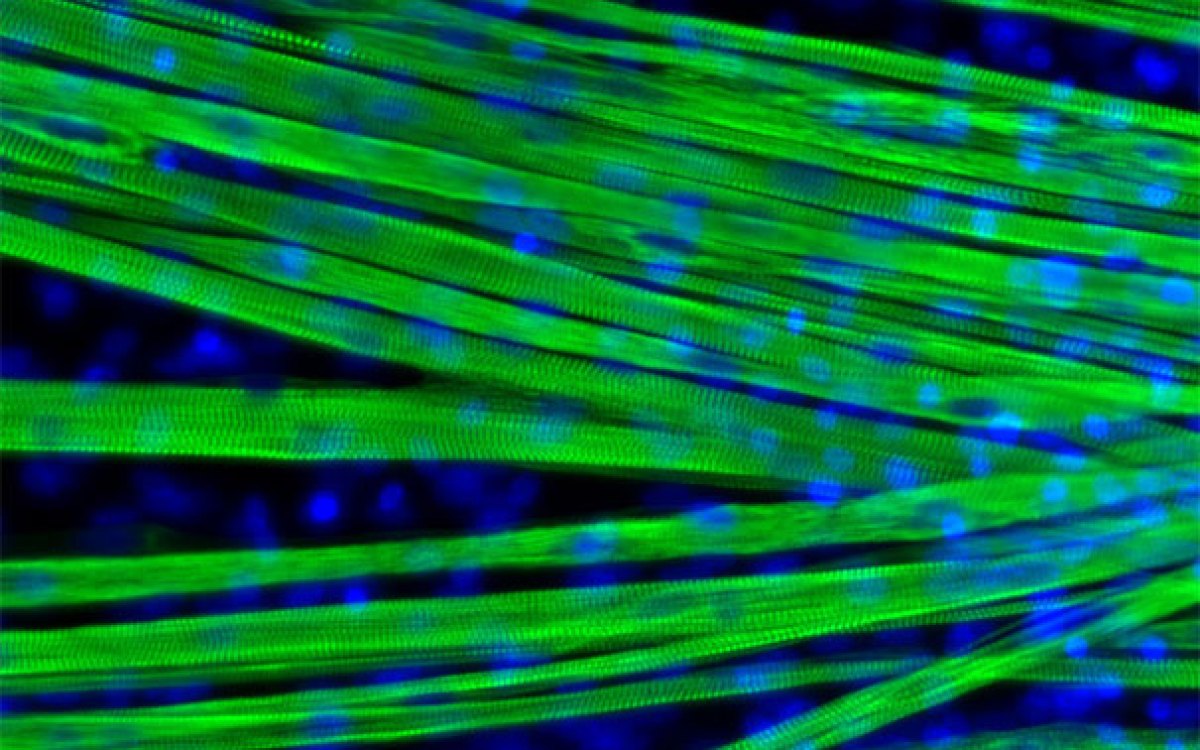

Cell signaling molecules, lit up in green, peak each time the segmentation clock ticks in human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

Video: Pourquié lab/HMS

Both models open new doors for understanding developmental conditions of the spine, such as congenital scoliosis, as well as diseases involving tissues that arise from the same region of the embryo, known as the paraxial mesoderm. These include skeletal muscle and brown fat in the entire body, as well as bones, skin, and lining of blood vessels in the trunk and back.

Pourquié hopes that researchers will be able to use the new stem cell models to generate differentiated tissue for research and clinical applications, such as skeletal muscle cells to study muscular dystrophy and brown fat cells to study Type 2 diabetes. Such work would provide a foundation for devising new treatments.

“If you want to generate systems that are useful for clinical applications, you need to understand the biology first,” said Pourquié, who is also the Harvard Medical School Frank Burr Mallory Professor of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Then you can make muscle tissue and it will work.”

Although scientists have derived many kinds of tissue by reprogramming adult cells into pluripotent stem cells and then coaxing them along specific developmental paths, musculoskeletal tissue proved stubborn. In the end, however, Pourquié and colleagues discovered that they could facilitate the transformation by adding just two chemical compounds to the stem cells while they were bathed in a standard growth culture medium.

“We can produce paraxial mesoderm tissue with about 90 percent efficiency,” said Pourquié. “It’s a remarkably good start.”

His team created a similar model derived from embryonic mouse cells.

The HMS researchers were surprised to find that the segmentation clock began ticking in both the mouse and human cell dishes and that the cells didn’t first need to be arranged on a 3D scaffold more closely resembling the body.

“It’s pretty spectacular that it worked in a two-dimensional model,” said Pourquié. “It’s a dream system.”

The team found that the segmentation clock ticks every five hours in the human cells and every 2.5 hours in the mouse cells. The difference in frequency parallels the difference in gestation time between mice and humans, the authors said.

Among the next projects for Pourquié’s lab are investigating what controls the clock’s variable speed and, more ambitiously, what regulates the length of embryonic development in different species.

“There are many very interesting problems to pursue,” he said.

Another group publishing in the Jan. 8 issue of Nature uncovered new insights into how cells synchronize in the segmentation clock using mouse embryos engineered to incorporate fluorescent proteins.

Pourquié is senior author of the HMS-led paper. Postdoctoral researcher Daniel Wagner of HMS is co-first author. Additional authors are affiliated with Kyoto University, RIKEN Center for Brain Science, and Brandeis University.

Pourquié has started a company called Anagenesis Biotechnologies based on protocols developed for this study. It uses high-throughput screening to search for cell therapies for musculoskeletal diseases and injuries.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant 5R01HD085121.