Visitors explore “Visual Science: The Art of Research” inside The Special Exhibition Gallery of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A collection of knowledge

Historical Scientific Instruments continues to teach and amaze

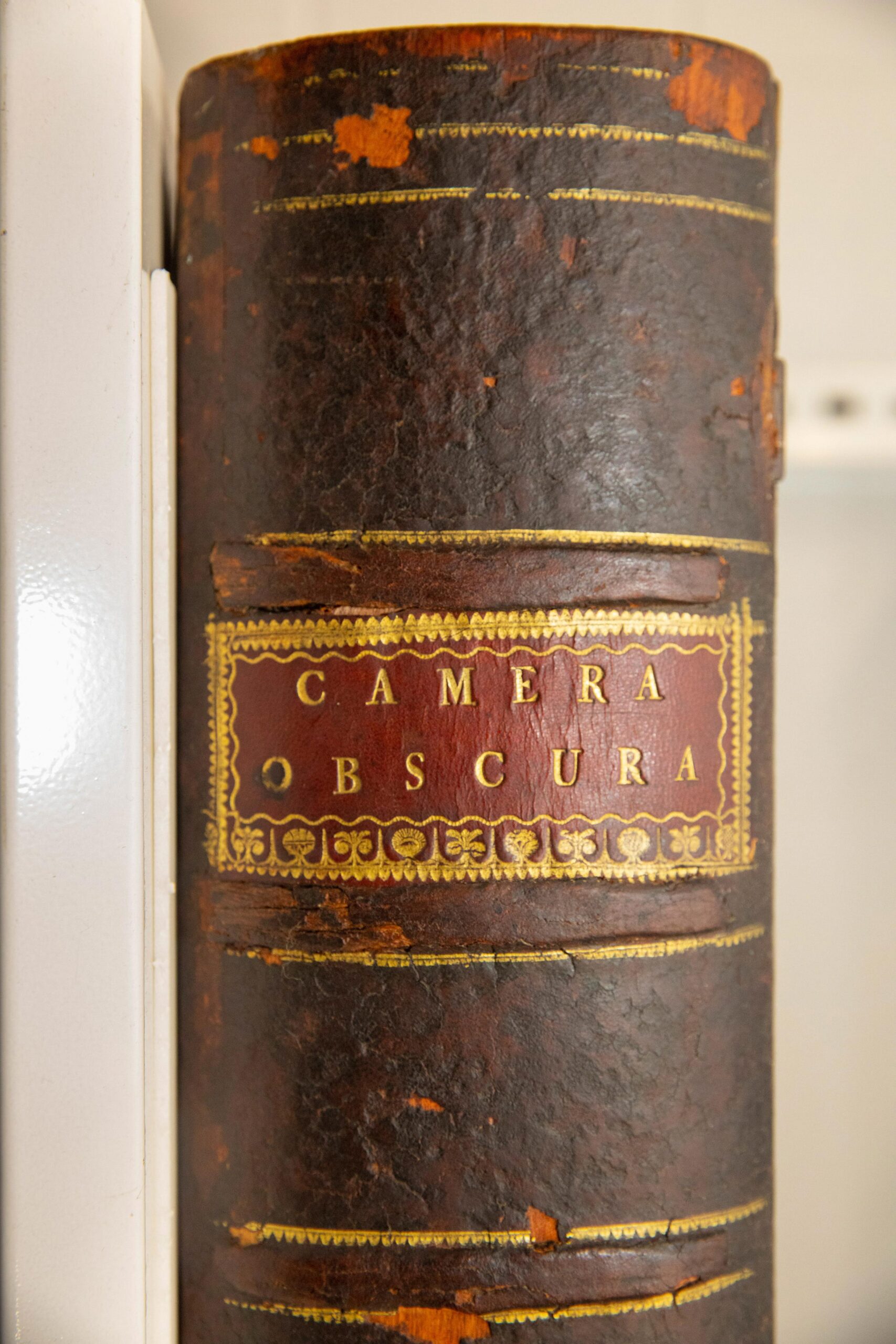

Since 1672, Harvard University has been acquiring scientific instruments for teaching and research. In 1948, the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments was established to preserve the objects as a resource for teaching and research in the history of science and technology. It has since grown to more than 20,000 objects making it one of the three largest university collections of its kind in the world. Originally associated with the Harvard Library system, the collection was placed under the stewardship of the Department of History of Science in 1987. Whether it’s the handmade globe electrical machine (circa 1750) Harvard President Edward Holyoke created using recycled materials to perform experiments with Professor John Winthrop or the camera obscura given to the College by Benjamin Franklin, these astonishing collections never cease to amaze.

A locally made tinfoil phonograph (left), circa 1878, demonstrates Thomas Edison’s latest invention for recording and playing back sound. It sits on a shelf near a theodolite made by Jones & Son, London, 1784, and a jumbo telephone crafted by Thomas Hall, Boston, circa 1874. Grooves are etched in tinfoil on a prototype of Thomas Edison’s Speaking Phonograph, 1878.

These 17th-century sand glasses measure time in 30- and 60-minute increments.

Benjamin Franklin selected this huge, book-shaped camera obscura (left) for Harvard College in 1765. It was among apparatus shipped from London to replace items lost in the Harvard Hall fire of 1764. This mahogany octant with an ivory scale and its original keystone case was made by John Bleuler, London (circa 1775‒1790), and later repaired in Salem, Mass., by Gedney King. After being used during nautical explorations, the instrument was used to teach Harvard College students the principles of navigation. In 1953, it was transferred to the collection from the Students’ Astronomical Laboratory.