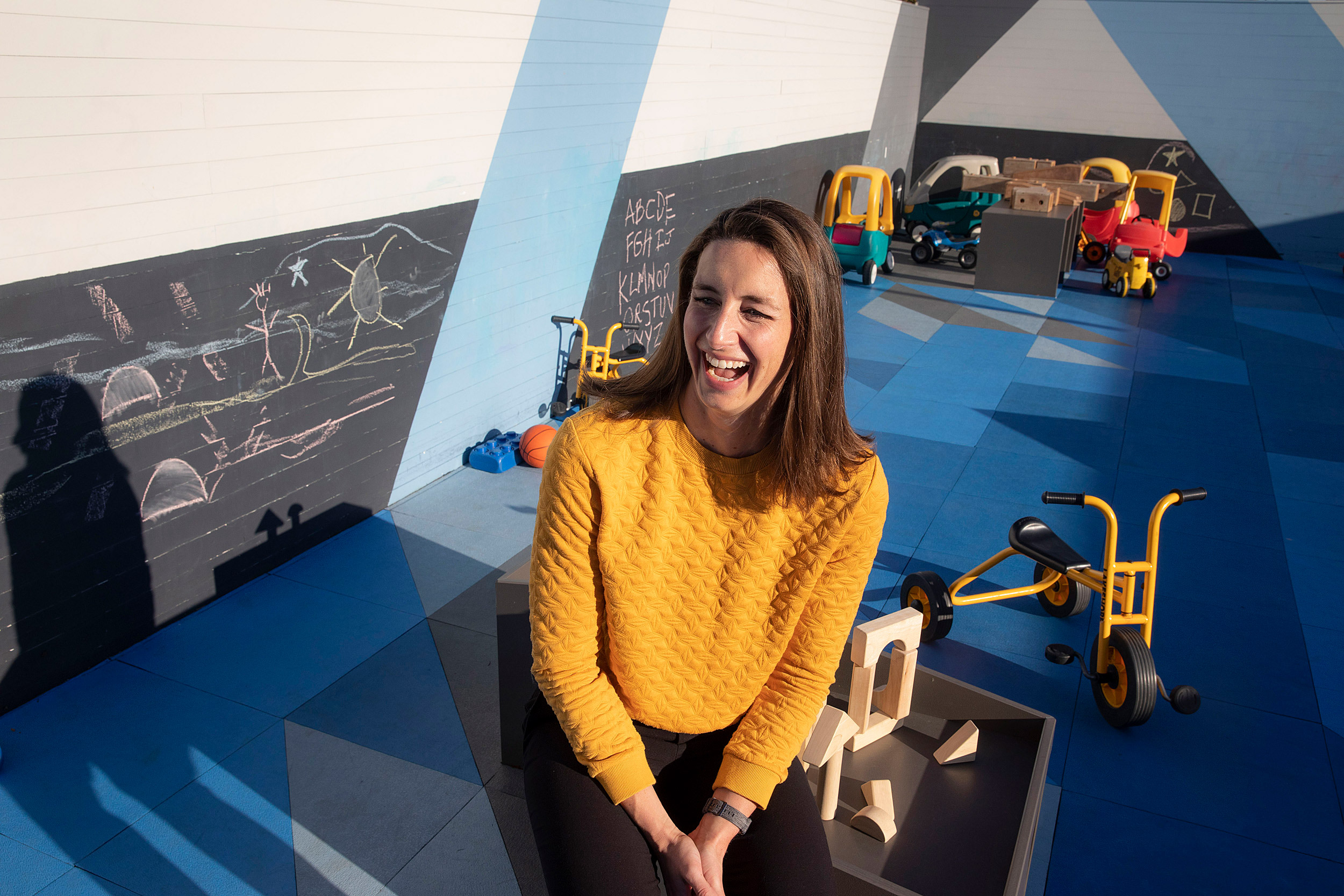

Power play

The 1,500-square-foot rooftop space, “High Sees,” sits atop Arlington’s Learn to Grow preschool.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘High Sees’ architect reasserts how play can impact mental, social development

Her young sons crawl the wrong way up playground slides and dangle from objects they’re not supposed to climb, and Megan Panzano is thrilled.

“We break rules now when we go to playgrounds,” says Panzano, assistant professor of architecture at the Graduate School of Design and director of the University’s Undergraduate Architecture Studies program. “One thing I’ve learned as a parent is how children can have strong, productive reactions, emotionally and physically, once we question the givens of rules and constraint when we play.”

Panzano has designed townhouses in South Boston, offices made of reclaimed materials in Charlestown, and a highway master plan in Somerville. Designing a playground had never crossed her mind until she and her husband found themselves, as new parents, immersed in a sea of literature on child psychology and development.

Panzano was intrigued especially by the idea of open-ended, unscripted play — activities without preset instructions. She warmed up to evidence that children develop in more complex and enriched ways when they are given fewer guidelines for play, allowing more room for exploration and imagination. She also dug into the tangential concept of “scaffolded parenting,” which posits that children grow to be more independent when given general frameworks for behavior, but not specific directives.

It wasn’t long before the architect was playing with these ideas in her sketchbook.

Over the course of a year, Panzano would devise “High Sees,” now open atop Arlington’s Learn to Grow preschool. The 1,500-square-foot rooftop space, which she calls a “perceptual playground,” is physically spare, absent of swing sets, metal slides, or other ephemera common to the American playground. Instead, geometric patterns of gray and blue rubber tiles dash across the ground and run up fence walls, resembling painted lines. The only other material used is gray plastic sheeting, a material used in the fabrication of speed boats, which makes up five platforms of different shapes and sizes, placed strategically around the playground.

The minimalism of High Sees negotiates between two considerations that Panzano wanted to harmonize: the power of open-ended play for young, developing minds, versus the highly specific, risk-averse building code that governs American playgrounds.

“With playgrounds, we face the design problem of identifying the loopholes or spaces in the heavy code requirements where you have some wiggle room to intercede and experiment with new form,” Panzano observes. “I struggled to find precedents in America that spoke to the lack of prescription and the open-ended play that I was gravitating toward.”

Instead, Panzano found inspiration in designer Isamu Noguchi, whose “Play Mountain” (1933) and related works present familiar but abstract shapes and images at scaled-up sizes, meant to simultaneously enchant and mystify young visitors and stoke their imaginations.

“Noguchi called his playscapes ‘educational’ specifically because of their open-endedness in relation to form, perception, and subsequent play,” Panzano observes. “I think that sensibility is quite appropriate today, and one that we don’t have opportunity to test enough.”

“It is very unstructured, and we allow the children to explore however they see fit. It truly promotes a sense of independence and autonomy for our children.”

Nicole Lowery, Learn to Grow

As she moved from researching to designing, Panzano sought to optimize spatial-cognitive development at a time when that growth is prime, roughly between ages 3 and 5. She also wanted to encourage peer-to-peer proximity to in turn engage children’s observation and communication skills.

“Depth perception and spatial cognition are uniquely attended to, tuned, and improved by having to work a bit to make sense of a relationship between a two-dimensional image and its three-dimensional spatial consequences,” she continues. “For preschoolers, these two aspects of visual-cognitive functioning are still being shaped, so the design of the playground became a way for me to design something that presents things that you may see, but don’t necessarily get in reality.”

Thus, the abstract patterns that carpet High Sees in blues and grays present optical illusions to “invite children into a dialogue between perception and reality,” Panzano says. Children can imagine various territories and play zones based on these geometric patterns, she adds, while imaginations of full figures — a river? a cloud?— emerge from flat lines.

Panzano also experimented with how to space the playground’s only physical play elements: five custom-made plastic blocks. Her intention was to distance these elements just right, balancing psychology with building code. She wanted children engaged in various activities across “High Sees” to be able to verbally discuss or visually observe what others are doing, and make new decisions from there — so-called “proximal play,” which psychologists argue can enable deeper social interaction and learning. But she would also need to follow Early Education and Care (EEC) safety code, which calls for, among other things, “fall zone” spacing in which children can safely tumble from a raised surface.

Panzano used digital software to experiment with different arrangements. As she would move one of the five block figures on screen, each of the other four would shimmy around the floor plate like chess pieces, reacting to EEC fall zone requirements.

“The project found areas where abstract forms, patterning, and proportion matched up with requirements of early education constraints to make something unexpected,” Panzano observes. “The opportunities for such play spaces are there, it just requires a design sensibility to read the code and match that with forms, arrangements, and assembly details that allow for the building of something new and unexpected.”

Amid a physically spare design, those five play platforms were designed to be ambiguous. Panzano had been seeking play elements that, unlike a slide or a swing set, refrain from suggesting a specific activity or use. Similarly, the generic grays and blues that color the space conjure up a portfolio of familiar visual environments, without prioritizing any single one.

In the playground’s first months of use, children have reimagined the platforms as pirate ships, mountains, vehicles, and caves, if not as stages for impromptu theater performances; amid its grays and blues, they have visualized themselves sailing on an ocean, floating in clouds, or walking across ice. And, while Panzano avoided prescribing set activities, the combination of flat shapes and physical platforms suggests a series of zones that, in turn, imply different modes of motor-skill engagement and play, she says: theatrical play, gross motor, fine motor, sensory play, and play-seeking.

“Our rooftop play space is very popular among children, parents, and educators alike,” says Nicole Lowery, program director of Learn to Grow. “It is very unstructured, and we allow the children to explore however they see fit. It truly promotes a sense of independence and autonomy for our children.” Some teachers and students bring chalk and paint to the play space, experimenting with color-mixing against the space’s color palette and using these play tools to expand or accentuate the stories their imaginations start writing.

As children and teachers at Learn to Grow continue to reimagine how they engage with High Sees, Panzano has gleaned takeaways that she hopes may apply to other building projects. Spaces where proximal interaction is fundamental — schools and offices, for instance — may benefit, she says, as could retail spaces and storefronts, for which image perception is a priority.

For now, though, Panzano’s focus is on fun. Alongside her teaching and her private practice, she has been engaging insights from “High Sees” in a series of new projects, including a line of toys.

“Time and space for unscripted activity and play are essential needs in all of our lives, which is sometimes easy to forget,” Panzano says. “Working on this project was a great reminder of that.”