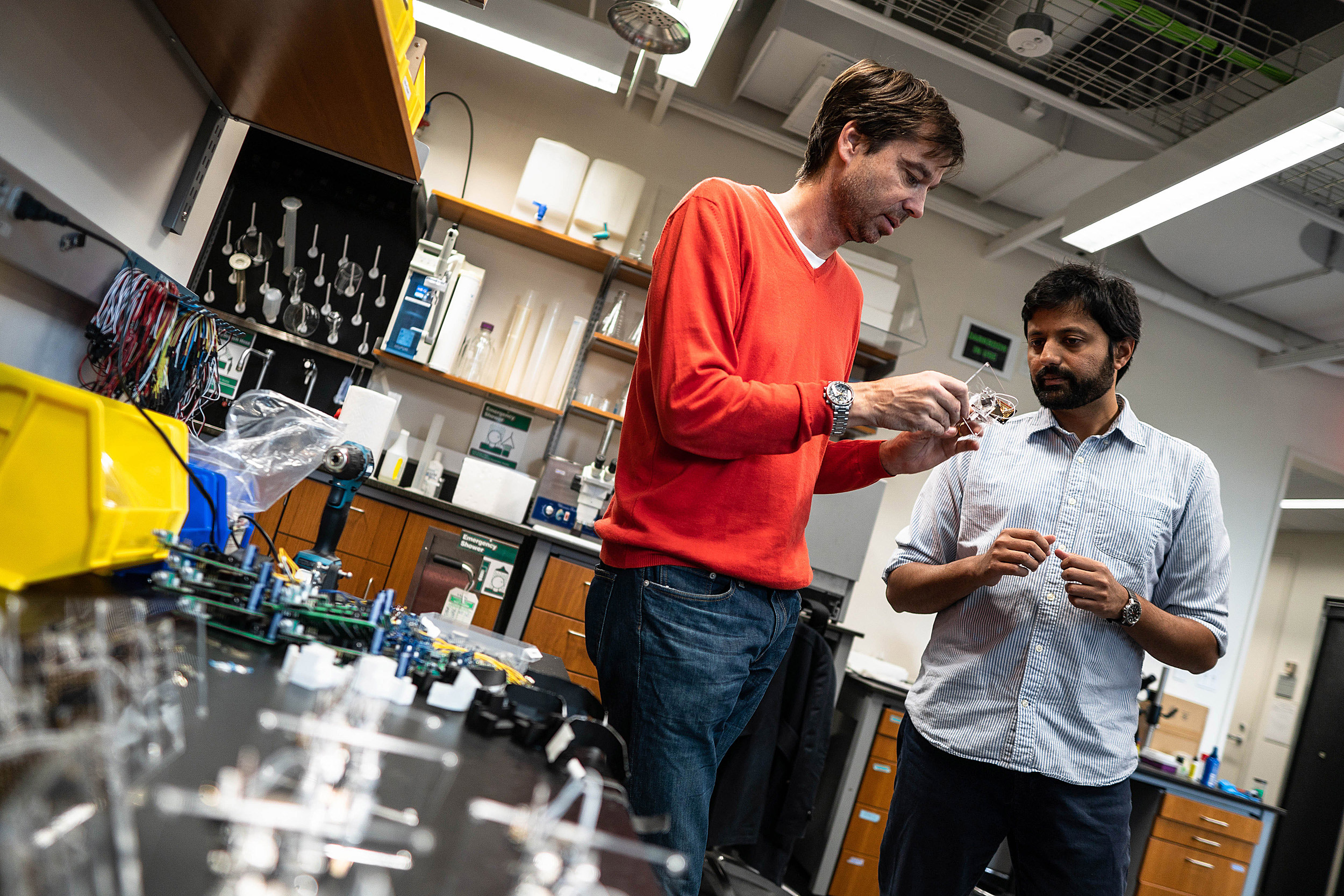

Principal Investigator Bence Ölveczky (left) and postdoctoral fellow Ashesh Dhawale with the device used to test variability in the motor function of rats.

Photos by Sophie Park

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

How the brain uses performance to regulate variability in motor functions

Anyone who has ever tried to serve a tennis ball or flip a pancake or even play a video game knows, it is hard to perform the same motion over and over again. But don’t beat yourself up —errors resulting from variability in motor function is a feature, not a bug, of our nervous system and play a critical role in learning, research suggests.

Variability in a tennis serve, for example, allows a player to see the effects of changing the toss of the ball, the swing of the racket, or the angle of the serve — all of which may lead to a better performance. But what if you’re serving ace after ace after ace? Variability in this case would not be very helpful.

If variability is good for learning but bad when you want to repeat a successful action, the brain should be able to regulate variability based on recent performance. But how?

That question was at the center of a recent study from Harvard researchers published in the journal Current Biology.

Using an enormous amount of data from about 3 million rat trials, the researchers found that rats regulate their motor variability based on the outcomes of the most recent 10 to 15 attempts at a task. If the previous trials have gone poorly, the rats increased their amount of variability — employing a try-anything approach. However, if the previous trials have gone well, the rats limited their variability, proving that rats too subscribe to the old adage “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

But is this the best strategy?

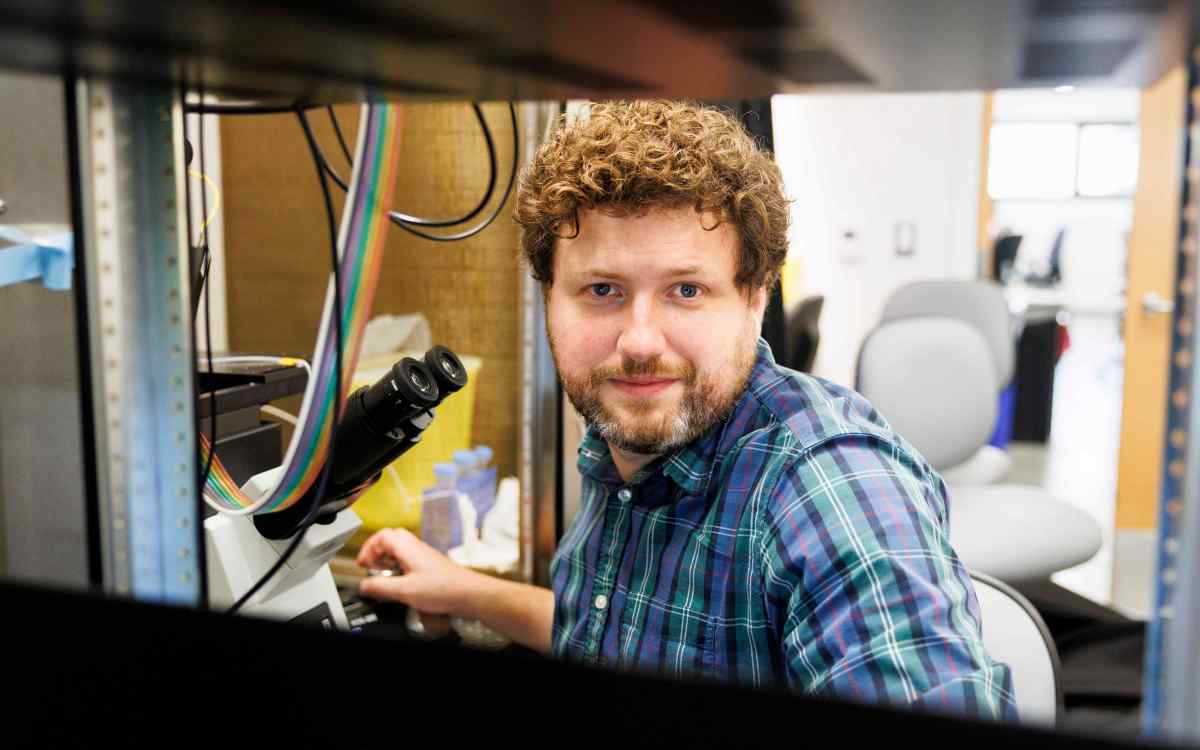

“By using simulations to determine what the optimal variability regulation strategy should be, we found that it was very similar to the one used by rats,” said Ashesh Dhawale, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and first author of the study. “We also found that the degree to which individual rats regulated variability could predict how well they learned and performed on the motor task. This means that regulating variability based on performance is important for doing well both in the short and the long term.”

To study performance-dependent variability, the researchers developed a new motor learning task for rats. The researchers, led by Bence Ölveczky, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology, trained rats to press a 2D joystick towards a target angle. When the rats were successful, they got a sip of water. To keep the task from getting too easy, the researchers changed the target angle whenever the rat learned its location.

The researchers found that when the rats were regularly getting rewarded, they had low variability. If, a few trials later, they did less well, their variability increased. If they continued doing poorly, the variability would increase even more.

“We noticed this was happening on a pretty fast time scale,” said Maurice Smith, the Gordon McKay Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and co-author of the paper. “It was as if the rats were computing their batting average in real time.”

But, what about longer-term tasks with less uncertainty? If you grew up playing tennis with your sister, for example, you may know that she has a consistently weak forehand.

The researchers simulated this scenario by keeping the target angle of the joystick fixed over many sessions instead of constantly changing it.

“We found that rats stopped regulating variability in response to recent performance, which matches what we found in our simulations,” said Dhawale. “Variability regulation in this case had a timescale of several thousand trials, which was much slower than the reward-dependent regulation of variability that we had uncovered earlier.”

“Our results demonstrate that the brain flexibly adapts components of its trial-and-error learning algorithm, such as the regulation of variability, to the statistics of the task at hand,” said Ölveczky. “We have shown that the brain uses a sophisticated algorithm to regulate motor variability in a way that improves task performance.”

The research was co-authored by Yohsuke R. Miyamoto.

The research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health.