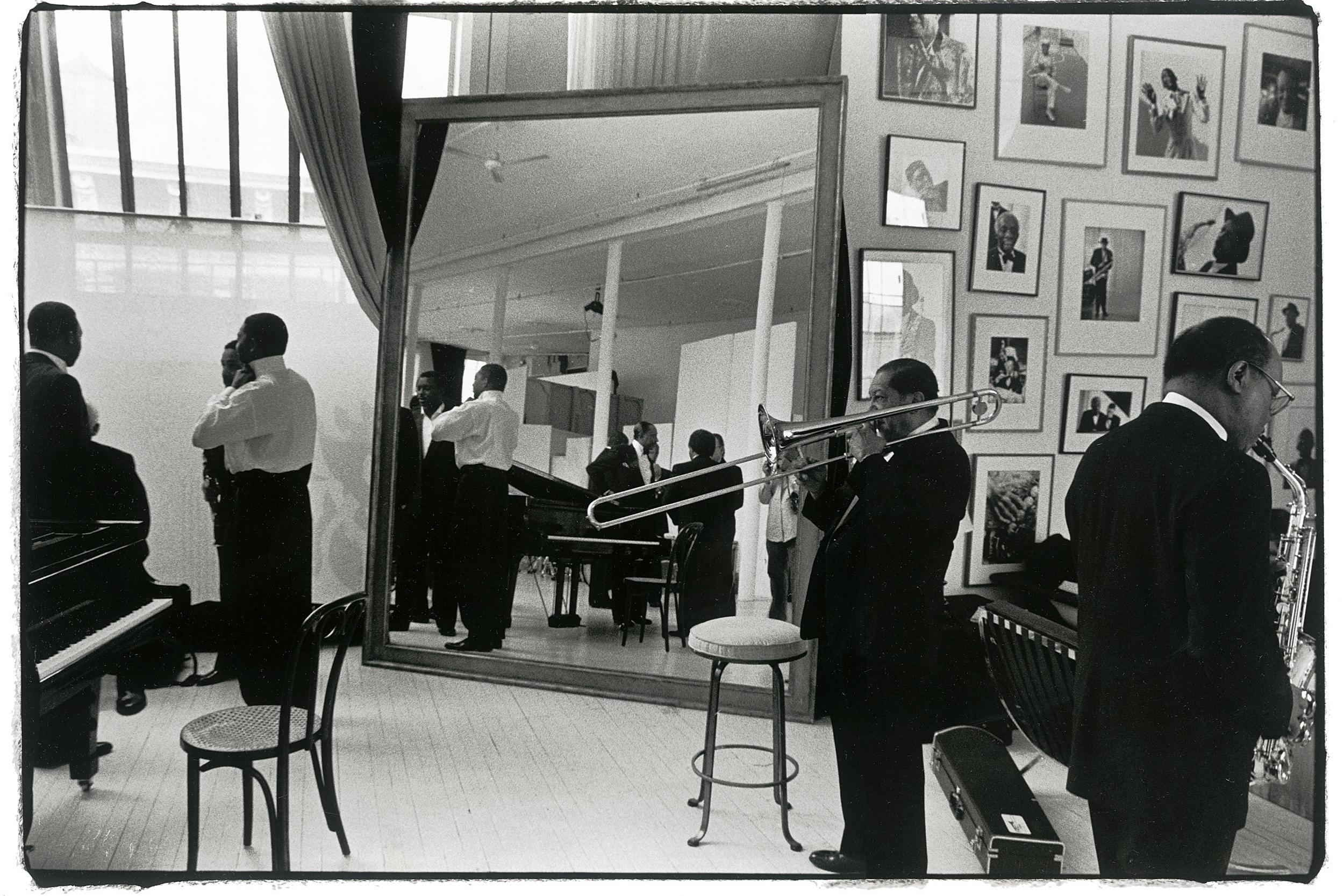

“The Bow, Modena, 1996” “After the show.”

Photos courtesy of Frank Stewart ©

The soul of a jazz man

Cooper Gallery features photo exhibit by Frank Stewart, who chronicled musicians

Frank Stewart learned young how to fail often with his camera.

A painter could spend days on a canvas only to realize the result was a “monstrosity,” the acclaimed photographer and artist said during a conversation with New York University Professor of Performance Studies Fred Moten ’84 at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research’s Hiphop Archive last week.

Stewart’s early missteps on film were evident as soon the negatives were developed. From 36 exposures came “36 chances to learn from those failures,” said Stewart, now 70, who snapped his first pictures as a teen at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, using a Brownie camera he borrowed from his mother.

Learning from his mistakes and bringing his life experiences to bear on his photographs are key to his practice, he said, as is embracing improvisation — the theme that runs through a new exhibit of his works at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art. In “The Sound of My Soul: Frank Stewart’s Life in Jazz,” nearly 80 black-and-white and color photographs large and small document Stewart’s fascination with capturing the country’s signature art form — one rooted in improvisation — on film.

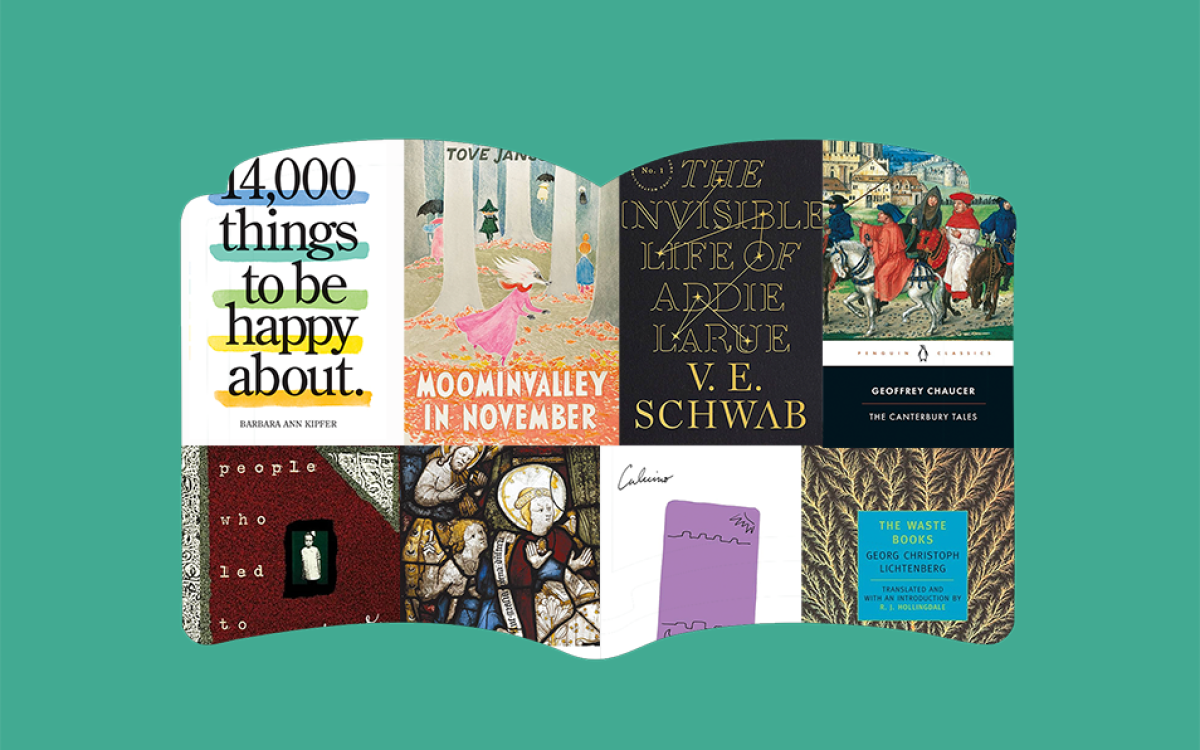

With jazz, “You are trying to improve on what you just played … you are looking forward to making something new all the time, and that’s what’s happening in photography,” said Stewart, Jazz at Lincoln Center’s official photographer since 1992. Through the years, he has repeatedly returned to the topic, haunting clubs, classrooms, and concert halls with his camera, creating silent images that convey a vivid sense of sound. And he has repeatedly improvised, playing with the forms his pictures took and the processes he employed as technology evolved from the darkroom to the digital age.

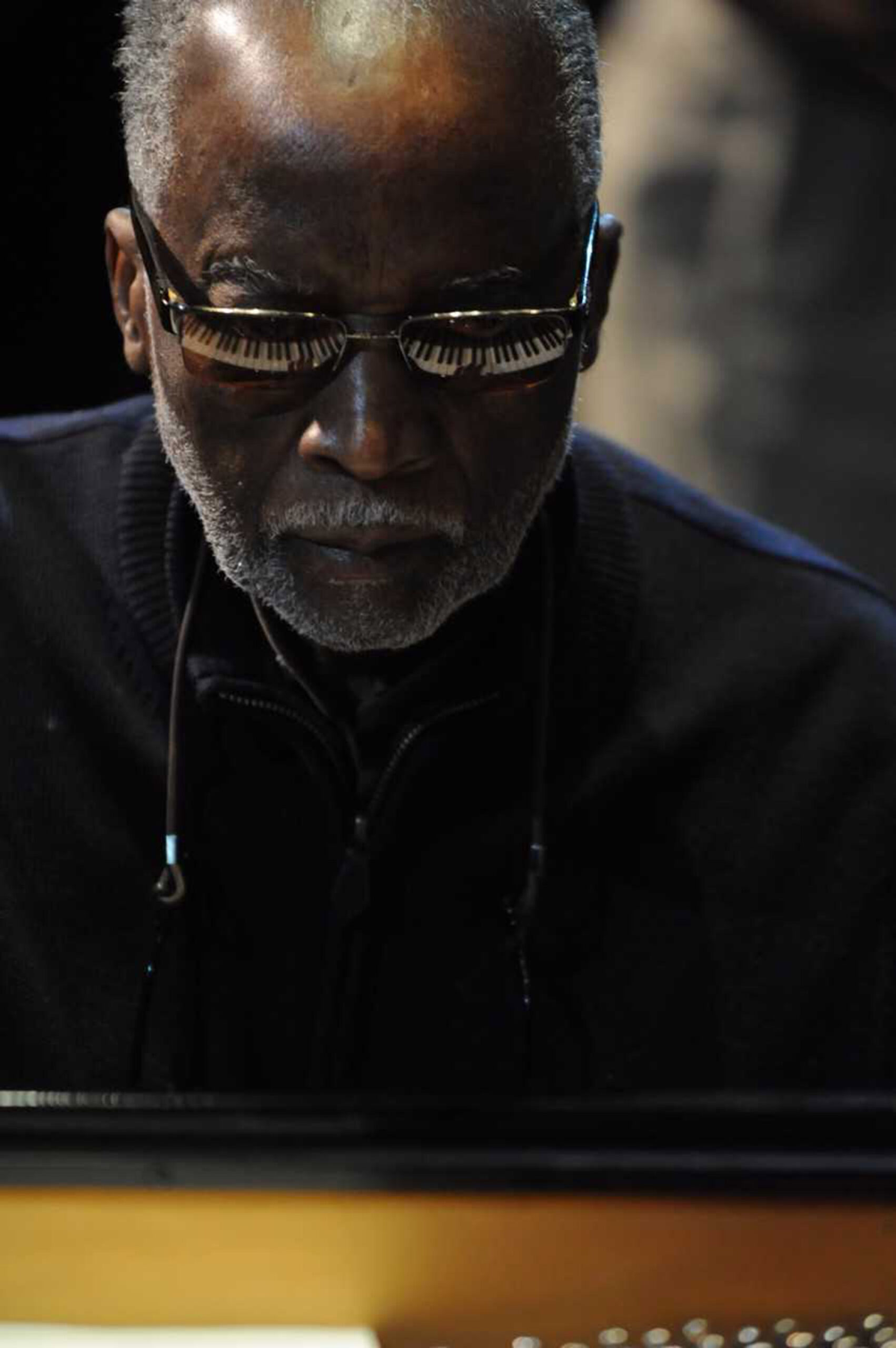

“Miles in the Green Room, 1981” “Christ-like figure in Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center.” “Jazz and Abstract Reality (aka Lincoln Center Orchestra, New York City) 1992” “The remaining members of Duke Ellington’s orchestra fused with Wynton’s Septet to form the original JALC Orchestra.”

Jazz as a focus of his lens seemed only natural for Stewart, who grew up in Memphis, Tenn., where music was a formative part of his early years. “The radio was on all the time,” he recalled, with Sundays devoted to Gospel, and weekdays given over to rhythm and blues. As a boy, Stewart also accompanied his stepfather, jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr., to Manhattan clubs where he met jazz greats including Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. After attending the Art Institute of Chicago and earning a bachelor of fine arts degree from Cooper Union in 1975, Stewart worked with jazz musician Ahmad Jamal, and later traveled with the Wynton Marsalis Septet from 1989 to 1992.

The Cooper show features a range of images from those years, and more, and includes his perhaps most famous jazz-related picture: a shot of Miles Davis leaning against a wall in the green room of Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall in 1981 following his first performance in two years. Davis’ casual pose is in stark contrast to the excitement of the surrounding press eager to record the legend’s return to the stage and spotlight. Other images of solitary performers waiting backstage, children blowing their earliest notes, musicians collaborating with dancers and singers, and artists deep into a set before a darkened crowd highlight the layers of form and meaning present both in Stewart’s art and in the music.

The Cooper exhibit conveys “the range of situations that he’s grasping … it shows the religious aspect, and the joyful and the meditative aspect of [jazz] for the musicians, and for the listeners, and for the viewers,” said curator Ruth Fine, the recently retired curator of special projects in modern art at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., who is working on a retrospective of Stewart’s work. “I think Frank wants to convey what his world is.

“‘The Sound of my Soul,’ I think that’s real,” Fine said. When looking at his photos, she added, “you can hear the music.”

Marsalis, who features in a number of the shots on the walls, and whose music is part of a soundtrack accompanying a looping video of a selection of Stewart’s other jazz-related pictures, summed up the photographer’s gift and his appreciation and understanding of the jazz world in an essay for the 2016 “Vision & Justice” issue of Aperture Magazine edited by Harvard’s Sarah Lewis.

“Frank loves black folks, but he focuses on timeless HUMAN fundamentals that only increase in value and intensity with time,” wrote Marsalis. “He is a jazzman with a camera. Improvisational, empathetic, and accurate, all kinds of folks trust him and let him in.”