Winslow Homer’s early oil paintings completed after the Civil War reflect the ways in which people were trying to cope with the staggering loss of life. In this work titled “The Brush Harrow,” two young boys till a field alone, suggesting their father has died in battle. © President and Fellows of Harvard College

The artist as witness

Harvard exhibit features Winslow Homer’s Civil War illustrations

It might surprise many to learn that one of America’s most beloved landscape artists trained his eye for the sea, surf, and sky on the front lines of the nation’s deadliest struggle.

Winslow Homer, whose famous windswept scenes viscerally evoke the rocky Maine coastline where he spent his later life, began his career in New York City newsrooms as a freelance illustrator for popular journals and periodicals. In 1861 the young, largely self-taught art correspondent made the first of three trips to the front to sketch the Civil War for the pages of Harper’s Weekly.

It was a fruitful time in the world of journalism for those with a talent for drawing what they saw. Photography’s time-consuming process and cumbersome equipment made it inefficient in the field. And publishers, eager to capture the conflict for their readers not only with words but with true-to-life images, turned to artists such as Homer for help.

“Winslow Homer: Eyewitness,” on view at the Harvard Art Museums through Jan. 5, 2020, traces how the artist’s experience as an observer tasked with accurately documenting the conflict helped shape his career and informed much of his later output. Throughout his work in a range of media, the Boston-born Homer often returned to the visual devices and motifs he had honed on the battlefield, depicting his subjects’ every small detail in order to convey an exact place, event, or time of day.

Homer is perhaps best known for his arresting seascapes, but he began his career as an illustrator for New York-based periodicals, and eventually covered scenes from the front lines of the Civil War for Harper’s Weekly. Above Homer’s “Schooner at Sunset” from 1880.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

“We are interested in thinking about Homer as witness because that is how he starts,” said Ethan Lasser, Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art, who organized the new show with Makeda Best, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography.

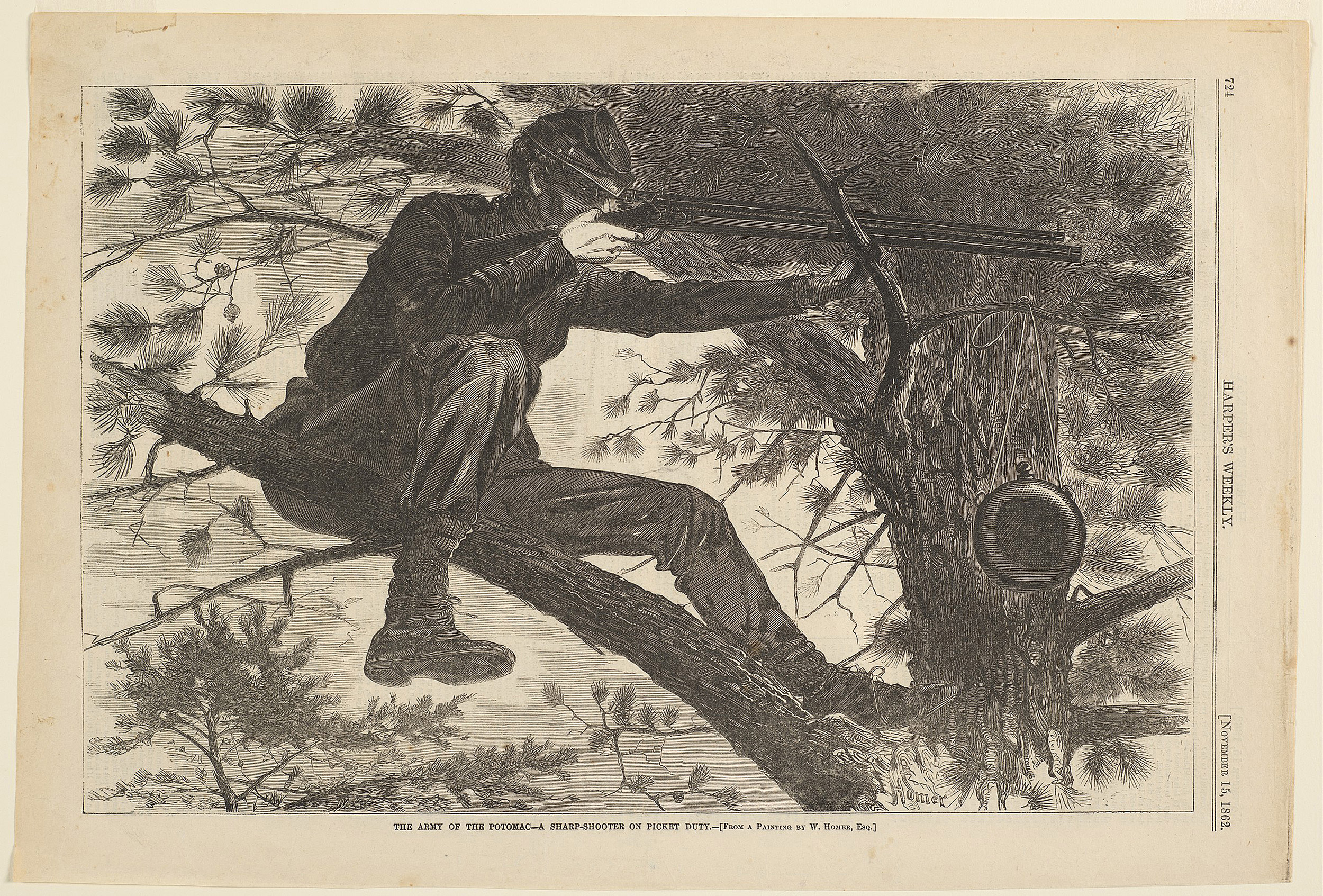

In his early illustrations Homer used a range of techniques to convince his viewers his art was grounded in fact, placing himself in many of his works, and paying close attention to the cut and color of soldiers’ uniforms, their equipment, and the broader material culture of war, said Lasser. He also registered the sky or the weather with his pen to dramatic effect, and did not shy from the brutality of battle. One of Homer’s most striking compositions, “Sharpshooter” shows a man perched in a tree training his gun on an approaching enemy. The drawing highlights the grim reality of the rifle, the war’s new weapon of choice that could kill with accuracy from a much greater distance than the traditional musket. Homer’s wasn’t the only one hand crafting the images he sent from the field. The show includes samples of the items engravers were using back in New York to add detail and flourishes to his drawings. Their contributions infused his work with additional meaning and context, said Best, and helped readers understand and interpret what they were seeing. “People had been looking at illustrated engravings since the 1850s but they’d never seen a war treated this way, a prolonged event, a national event,” she said. The end product was less about truth, Best said, “and more about storytelling.”

In “The Army of the Potomac – A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty” Homer captured the grim reality of a newly preferred weapon of war, the rifle, that could kill with greater accuracy and from a greater distance than the traditional musket.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Also included in the show are a handful of photographs that helped the public better grasp the war’s brutal cost. Limited by their technology, photographers trained their lenses on the aftermath of conflict, capturing images of a battlefield scattered with bodies, the scarred back of a former slave, or the appalling conditions at a Confederate prison camp. “Homer was working in a community of artists as eyewitness,” said Best, “and photographers were a key part of that.”

Two major works of oil on canvas completed roughly at the same time, “Prisoners from the Front,” on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Harvard’s “The Brush Harrow,” illustrate both Homer’s burgeoning talent with the brush and his continued interest in bearing witness to life as it unfolded. The paintings not only employ the same kind of fine detail that rendered his drawings so rich and lifelike, revealing Homer’s “commitment to witnessing carried through to this new material,” said Lasser, their subject matter points to the ways Americans were reckoning with the aftermath of the fighting and the unprecedented number of dead.

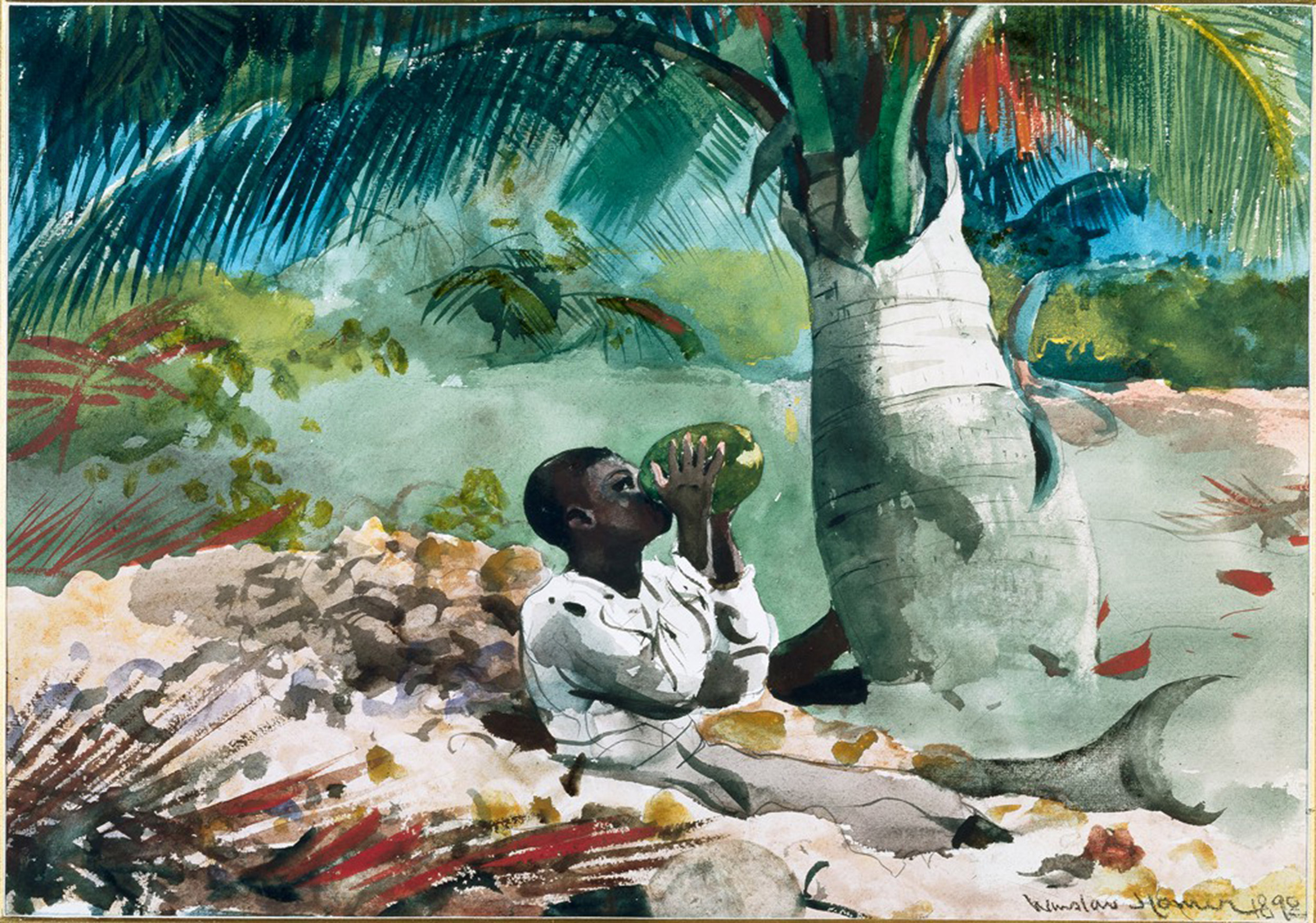

Homer turned to watercolor, with “Under the Coco Palms,” done in the late 1880s during his frequent trips to the tropics. Throughout his life and artistic career, the theme of witnessing was ever present in Homer’s work. In “Watching the Tempest,” from 1881, men launch a boat as they look out at an unseen storm.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

In “The Brush Harrow,” from 1865, two boys ready a field for planting. After a recent cleaning, museums’ conservationists uncovered the faded letters “US” on the animal’s flank, signifying the horse belonged to a union solider. The muted tones of the somber image suggest the boys have been left with the daunting task of tilling the land on their own.

“This discovery solidifies what we always surmised about this painting, which is that the horse has come back. The horse is the veteran but its lost its rider,” said Lasser. “So these boys are alone in the field without their elders who have been left on the battlefield.

While Homer’s interest turned from illustrations and oil to watercolors, his attention to witnessing never waned. The show’s final pairings match some of his early illustrations with his later works and underscore the artist’s lifelong fascination with looking. In his 1863 illustration “The Approach of the British Pirate ‘Alabama,’” a man on the deck spies the approach of the infamous Confederate battleship through a telescope. Nearby hangs “Watching the Tempest,” a moody watercolor created in 1881 that depicts a group of men preparing to launch a rescue boat as they look out on a raging storm, the sea hidden to the viewer by a gauzy mist. “In these images you really see the through line of witnessing as one ongoing preoccupation in Homer’s work,” said Lasser.

But there were limits to the truth Homer presented, as his depiction of African Americans, another theme curators chose to highlight in the new show, makes clear. “Homer’s efforts to present himself as a truthful witness sometimes involved distorting reality to fit the biases of his audience,” reads the wall text that accompanies the final works in the exhibit. “Nowhere was this tendency clearer than in his portrayal of men and women of African descent.”

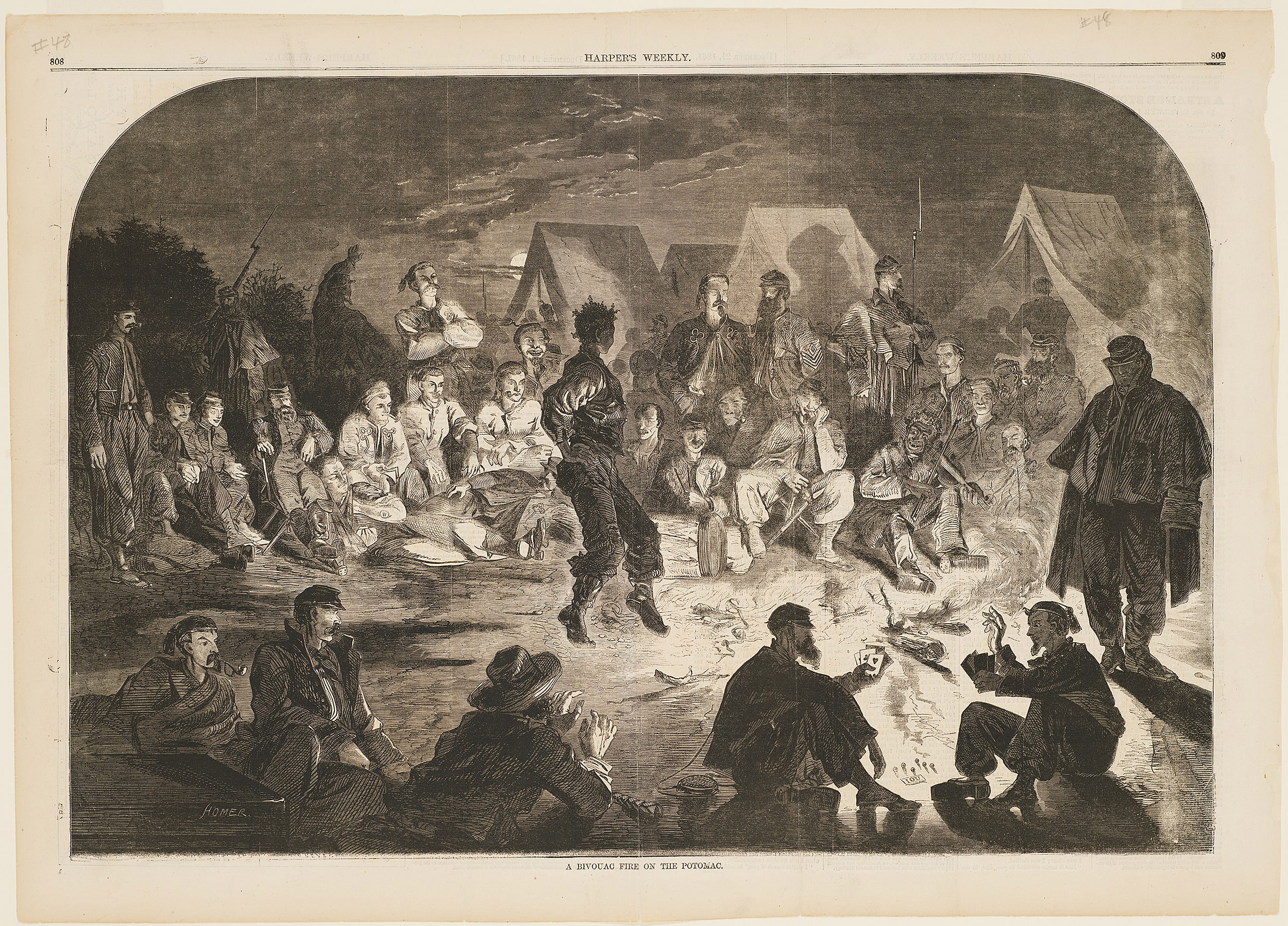

Homer’s depiction of African American subjects is another theme running throughout the show. In certain works, said curator Ethan Lasser, “Homer as witness suffered from the biases of his time.” Above “Bivouac Fire on the Potomac.”

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

In Homer’s illustration from 1861 “A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac,” a former slave dances for Union troops. In “Under the Coco Palm,” and “Sea Garden, Bahamas,” two watercolors done during Homer’s visits to the Atlantic Ocean archipelago in the late 1800s, islanders lounge in the sun and pull coral from the sea. Homer’s choice of subject matter and his execution raise questions for the viewer, said Lasser, who noted, “Homer as witness suffered from the biases of his time.” In “A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac,” he said, “The image of a freed slave who crossed Union lines and is dancing for others is a very stereotyped image; he is not working, he is not a soldier, he is entertainment for the troops.” Similarly, his watercolors neglect the narrative of the residents of the Caribbean as key figures in a growing tourist and fishing industry, offering up instead, said Lasser, “primitivizing views with no context.”

“Winslow Homer: Eyewitness,” is on view through January 5, 2020 in the museums’ University Research Gallery.

Oliver Wunsch, former Maher Curatorial Fellow of American Art, and Jovonna Jones, a Ph.D. candidate in African and African American Studies at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and a graduate intern in American Art, also contributed to the show.