In this artist’s concept, the moon Ganymede orbits the giant planet Jupiter. A saline ocean under the moon’s icy crust best explains shifting in the auroral belts measured by the Hubble telescope. Astronomers have long wondered whether Jupiter’s moons would be habitable if radiation from the sun increased.

Image: NASA/ESA

A ‘Goldilocks zone’ for planet size

Research redefines lower limit for planet size habitability

In “The Little Prince,” the classic novella by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the titular prince lives on a house-sized asteroid so small that he can watch the sunset any time of day by moving his chair a few steps.

Of course, in real life, celestial objects that small can’t support life because they don’t have enough gravity to maintain an atmosphere. But how small is too small for habitability?

In a recent paper, Harvard University researchers described a new, lower size limit for planets to maintain surface liquid water for long periods of time, extending the so-called habitable zone or “Goldilocks zone” for small, low-gravity planets. This research expands the search area for life in the universe and sheds light on the important process of atmospheric evolution on small planets.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

“When people think about the inner and outer edges of the habitable zone, they tend to only think about it spatially, meaning how close the planet is to the star,” said Constantin Arnscheidt ’18, first author of the paper. “But actually, there are many other variables to habitability, including mass. Setting a lower bound for habitability in terms of planet size gives us an important constraint in our ongoing hunt for habitable exoplanets and exomoons.”

Generally, planets are considered habitable if they can maintain surface liquid water (as opposed to frozen water) long enough to allow for the evolution of life, conservatively about 1 billion years. Astronomers hunt for these habitable planets within specific distances of certain types of stars — stars that are smaller, cooler and lower mass than our sun have a habitable zone much closer than larger, hotter stars.

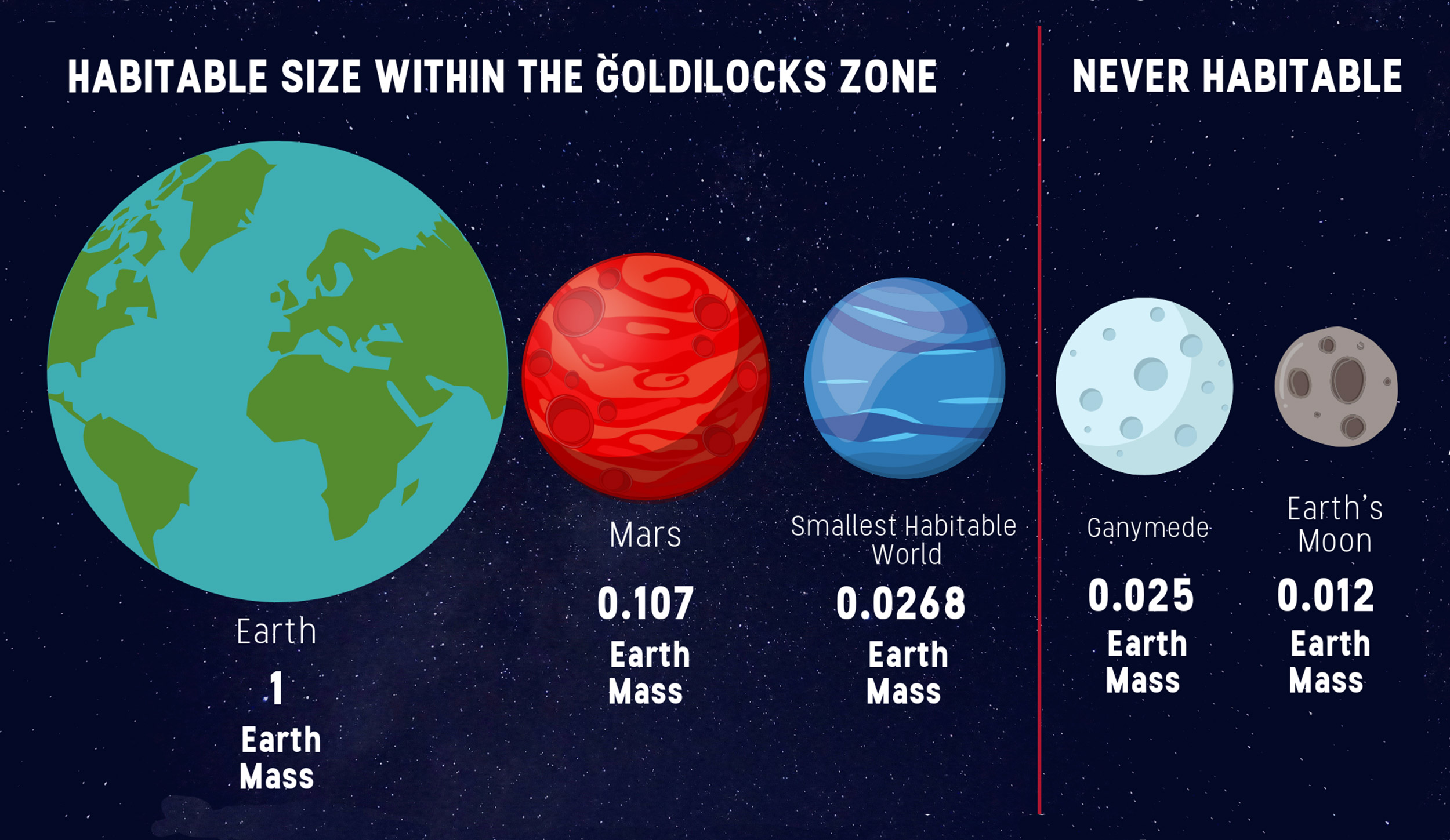

This illustration shows the lower bound for habitability in terms of planet mass. If an object is smaller than 2.7 percent the mass of Earth, its atmosphere will escape before it ever has the chance to develop surface liquid water.

Illustration courtesy of Harvard SEAS

The inner edge of the habitable zone is defined by how close a planet can be to a star before a runaway greenhouse effect leads to the evaporation of all surface water. But, as Arnscheidt and his colleagues demonstrated, this definition doesn’t hold for small, low-gravity planets.

The runaway greenhouse effect occurs when the atmosphere absorbs more heat that it can radiate back out into space, preventing the planet from cooling and eventually leading to unstoppable warming that finally turns its oceans turn to steam.

However, something important happens when planets decrease in size: As they warm, their atmospheres expand outward, becoming larger and larger relative to the size of the planet. These large atmospheres increase both the absorption and radiation of heat, allowing the planet to better maintain a stable temperature. The researchers found that atmospheric expansion prevents low-gravity planets from experiencing a runaway greenhouse effect, allowing them to maintain surface liquid water while orbiting in closer proximity to their stars.

When planets get too small, however, they lose their atmospheres altogether and the liquid surface water either freezes or vaporizes. The researchers demonstrated that there is a critical size below which a planet can never be habitable, meaning the habitable zone is bounded not only in space, but also in planet size.

The researchers found that the critical size is about 2.7 percent the mass of Earth. If an object is smaller than 2.7 percent the mass of Earth, its atmosphere will escape before it ever has the chance to develop surface liquid water, similar to what happens to comets today. To put that into context, the moon is 1.2 percent of Earth mass and Mercury is 5.53 percent.

The researchers were also able to estimate the habitable zones of these small planets around certain stars. Two scenarios were modeled for two different types of stars: a G-type star like our own sun and an M-type star modeled after a red dwarf in the constellation Leo.

The researchers solved another long-standing mystery in our own solar system. Astronomers have long wondered whether Jupiter’s icy moons Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto would be habitable if radiation from the sun increased. Based on this research, these moons are too small to maintain surface liquid water, even if they were closer to the sun.

“Low-mass water worlds are a fascinating possibility in the search for life, and this paper shows just how different their behavior is likely to be compared to that of Earth-like planets,” said Robin Wordsworth, associate professor of environmental science and engineering at SEAS and senior author of the study. “Once observations for this class of objects become possible, it’s going to be exciting to try to test these predictions directly.”

This paper was co-authored by Feng Ding, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

This work was supported by NASA Habitable Worlds grant NNX16AR86G.