Harvard researcher Erin Hecht published a paper which found that canine brains vary based on breed.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hunters, herders, companions: Breeding dogs has reordered their brains

Canine research lends insights into understanding the evolution of the human mind

Erin Hecht, speaking as both scientist and dog lover, explained how her interests came together:

“They beg to be analyzed,” said the assistant professor of neuroscience in the department of Human Evolutionary Biology. “You find yourself constantly thinking about what goes on in their heads.”

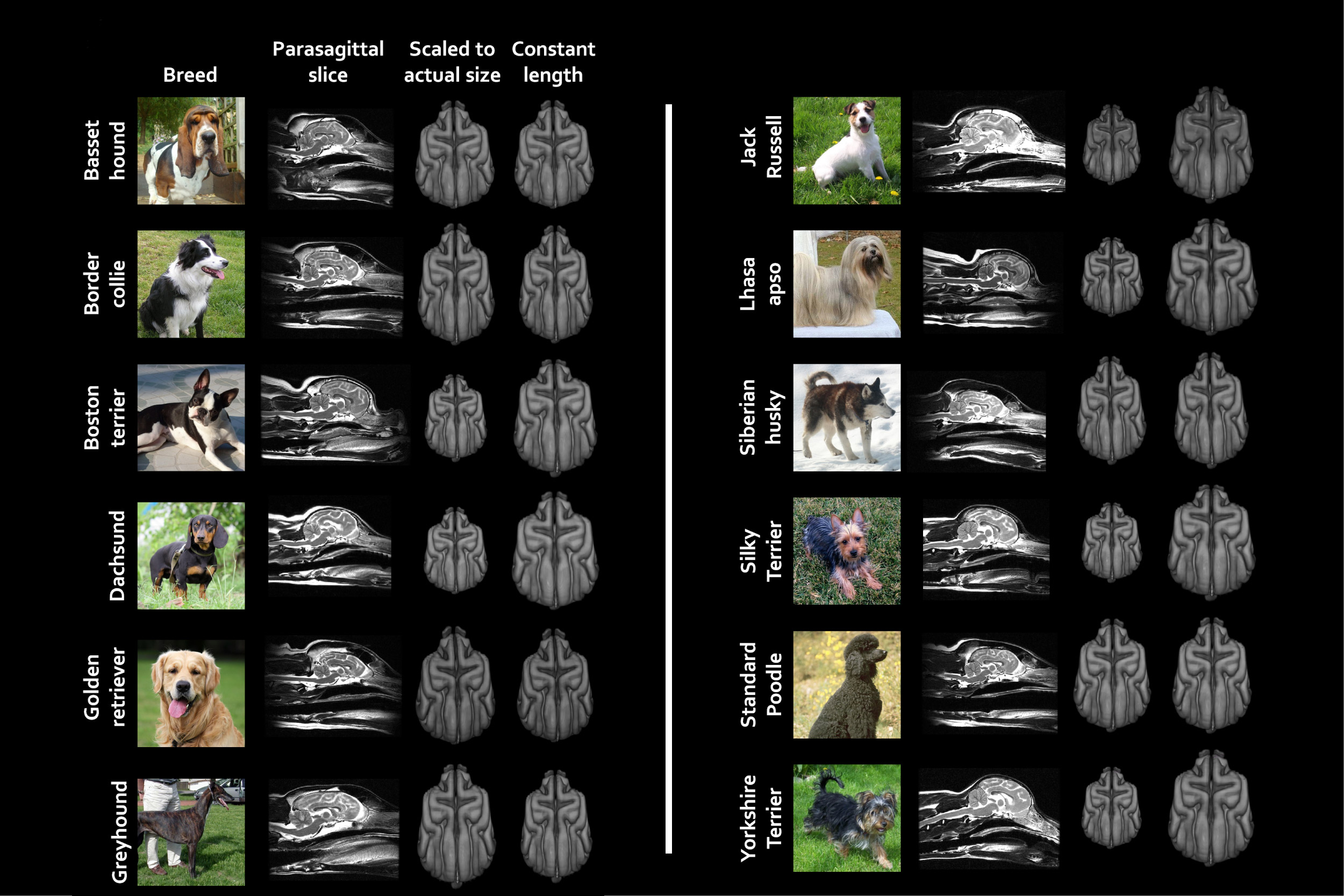

Hecht, who joined the faculty in January, has published her first paper on our canine comrades in the Journal of Neuroscience, finding that different breeds have different brain organizations owing to human cultivation of specific traits. Using MRI scans from 63 dogs of 33 breeds, Hecht found neuroanatomical features correlating to different behaviors such as hunting, guarding, herding, and companionship. Sight hunting and retrieving, for example, were both tied to a network that included regions involved in vision, eye movement, and spatial navigation.

“In my career so far, there have been a couple times when you look at the raw images and know there is something there even before you do statistics. This was one of these times,” she said. “I was like ‘Holy cow! How come no one else has done this?’”

Hecht isn’t entirely sure why dogs have not been long considered proper study subjects, but she theorizes that it’s easy to dismiss what lies at your feet.

“It was weird to be doing this back in 2012. When I told people, some would say, ‘Oh that’s cute,’” she said. “It took a long time to convince other scientists and funding agencies that dogs could really tell us something about brain evolution.”

Source: “Significant neuroanatomical variation among domestic dog breeds,” Erin E. Hecht, Jeroen B. Smaers, William J. Dunn, Marc Kent, Todd M. Preuss and David A. Gutman

Hecht came to researching dogs by way of a side project while in graduate school at Emory University studying human brain evolution. Seven years ago, she found herself watching a nature show about domestic dogs and selectively bred Russian foxes. The scientist studying the dogs and foxes discussed genetics and evolution, but there was no mention of neuroscience.

“I thought, ‘How is this possible? No one’s thought about looking at their brains,’” Hecht recalled.

She reached out to Lyudmila Trut at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics (part of the Russian Academy of Sciences) in Siberia. Trut connected her with researchers working on domesticated foxes, who gave her a half dozen brains for a pilot study. Around the same time, Hecht found Marc Kent, a veterinary neurologist at University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, who shared dozens of MRI scans of his four-legged patients.

“I had this data set and felt lucky I had access to it,” she said. “After a couple of years, the [National Science Foundation] funded the study to continue studying dogs and these foxes.”

Sitting in her office above the Museum of Comparative Zoology, flanked by her own Australian shepherds, Lefty and Izzy, Hecht said she and her collaborators were able see that the breed differences weren’t randomly distributed, but were, in fact, focused in certain parts of the brain. They examined variability, pinpointing six networks of the brain where anatomy correlated with types of processing important for different breeds: reward, olfaction, eye movement, social action and higher cognition, fear and anxiety, and scent processing and vision.

There were some surprises. For example, skill in hunting by scent was not associated with the anatomy of the olfactory bulb. “Rather, this skill was linked to higher-order regions that are involved in more complex aspects of scent processing,” she said. “It’s not about having a brain that can detect if the scent is there. It’s about having the neural machinery to decide what to do with that information.”

Hecht’s lab also studies brain evolution in humans, but she said continuing the dog research provides a window into understanding the human mind.

Miniature Australian Shepherd Lefty checks out a brain model.

“Border collies are amazing at herding, but they aren’t born knowing how to herd. They have to be exposed to sheep; there is some training involved. Learning plays a crucial role, but there’s clearly something about herding that’s already in their brains when they are born. It’s not innate behavior, it’s a predisposition to learn that behavior. That’s analogous to what goes on with humans with language. They don’t pop out of the womb being able to speak, but clearly all humans are predisposed in a very significant way to learn language. If we can figure out how evolution got those skills into dog brains, it might help us understand how humans evolved the skills that separate us from other animals,” she said.

To that end, Hecht is now studying dogs specifically bred for performance. With the help of Sophie Barton, a Ph.D. candidate in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the lab is currently recruiting a number of working dog breeds, including highly skilled German shepherds engaged in schutzhund (military obedience) training, border collies who compete in herding competitions, retrievers who excel at field trials, and more. They are studying both champion dogs and their low-skill littermates.

“We’re looking for animals raised in the same environment where, for whatever reason, one has excelled and one dropped out,” she said.

That will give researchers a better sense of how recent evolution of dog brains shaped the anatomy inherited from their ancestors, even if it’s “an evolutionary eyeblink.” And, as for the question she gets asked most — “What’s the smartest dog?” — Hecht has the science to back up her diplomatic answer.

“This research suggests there’s not one type of canine intelligence,” she said. “There are multiple types.”