Frank Keutsch and fellow researchers are working on a controversial idea that might someday be our best hope against climate change: stratospheric aerosol injection.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

An umbrella to combat warming

Research examines the possibility of spraying tiny particles into the stratosphere to block the sun a bit and cool the planet

Every morning, the Keutsch Research Group gathers for a meeting. Eight engineers and chemists give updates on their preceding day’s work: ordering parts, transferring software, untangling an administrative snafu. The whole affair usually lasts less than 15 minutes.

Scheduling vacations and requisitioning supplies do not scream “high stakes,” but the group’s project could someday have major consequences for global climate change. It is controversial, however. Some even fear it could make things worse. Right now the group is waiting for approval to schedule a new experiment in the stratosphere.

Their idea? To shield the Earth with a mist of tiny particles. It sounds like the stuff of sci-fi movies, but since it was first proposed in the 1950s the idea has gained traction among scientists around the world to shield us not from extraterrestrials, as Hollywood might have it, but from the sun. Known as solar geoengineering, the concept is to send planes into the stratosphere — 6 to 31 miles above the Earth — to spray particles that can reflect sunlight back into space and cool the planet.

Working in collaboration with colleagues from the Keith Group — more than a dozen environmental scientists, engineers, economists, and political scientists under the leadership of David Keith, Gordon McKay Professor of Applied Physics at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and a professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School — the Keutsch Group is hoping to uncover some answers about the possibilities of such a scheme with a project they call the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment, or SCoPEx.

The need for a bold new plan seems clear.

Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions reached an all-time high in 2018. In October, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) announced that those emissions must drop drastically to limit global warming to acceptable levels. In 2017, according to the IPCC, global warming reached 1 degree Celsius above preindustrial levels. To keep it from going more than half a degree higher, the panel recommends cutting emissions by about 45 percent by 2030 and to “net zero” by 2050. The panel’s website concedes, however, that even these drastic changes would mean that “any remaining emissions would need to be balanced by removing CO2 from the air.”

In other words, Professor Frank Keutsch said, “if we do only emissions cuts to reach the panel’s goals, we would need to get them to zero by 2021 or ’22, and that’s clearly never going to happen. It’s a purely utopian idea. Because of this, they include in their models a negative-emissions technology that we don’t have yet. It doesn’t exist.” The amount of land this IPCC-imagined equipment would need if it did exist, he added, is a parcel about the size of India.

But as the deadline for reducing emissions approaches, scientists have become more open to engineering solutions. “One thing that we know can cool down the planet quickly is putting particles into the stratosphere,” Keutsch said. Natural events have taught us that: In 1991, the Philippines’ Mount Pinatubo erupted, releasing 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. Afterward, the entire globe cooled by half a degree Celsius for more than a year.

Mimicking that sort of impact could have any number of side effects, including changes in weather patterns. Keutsch doesn’t think the particles would cause haze but said they could give our sunrises more vivid reds. The problem is that it’s hard to judge the odds of what might happen without more data.

“If in 20 years climate impact suddenly becomes bad and the public starts demanding fast action,” he said, “my concern is that we could get to a situation where sudden decisions are made, and we don’t have enough information to make them. I see my role as providing information on the risks of various scenarios.”

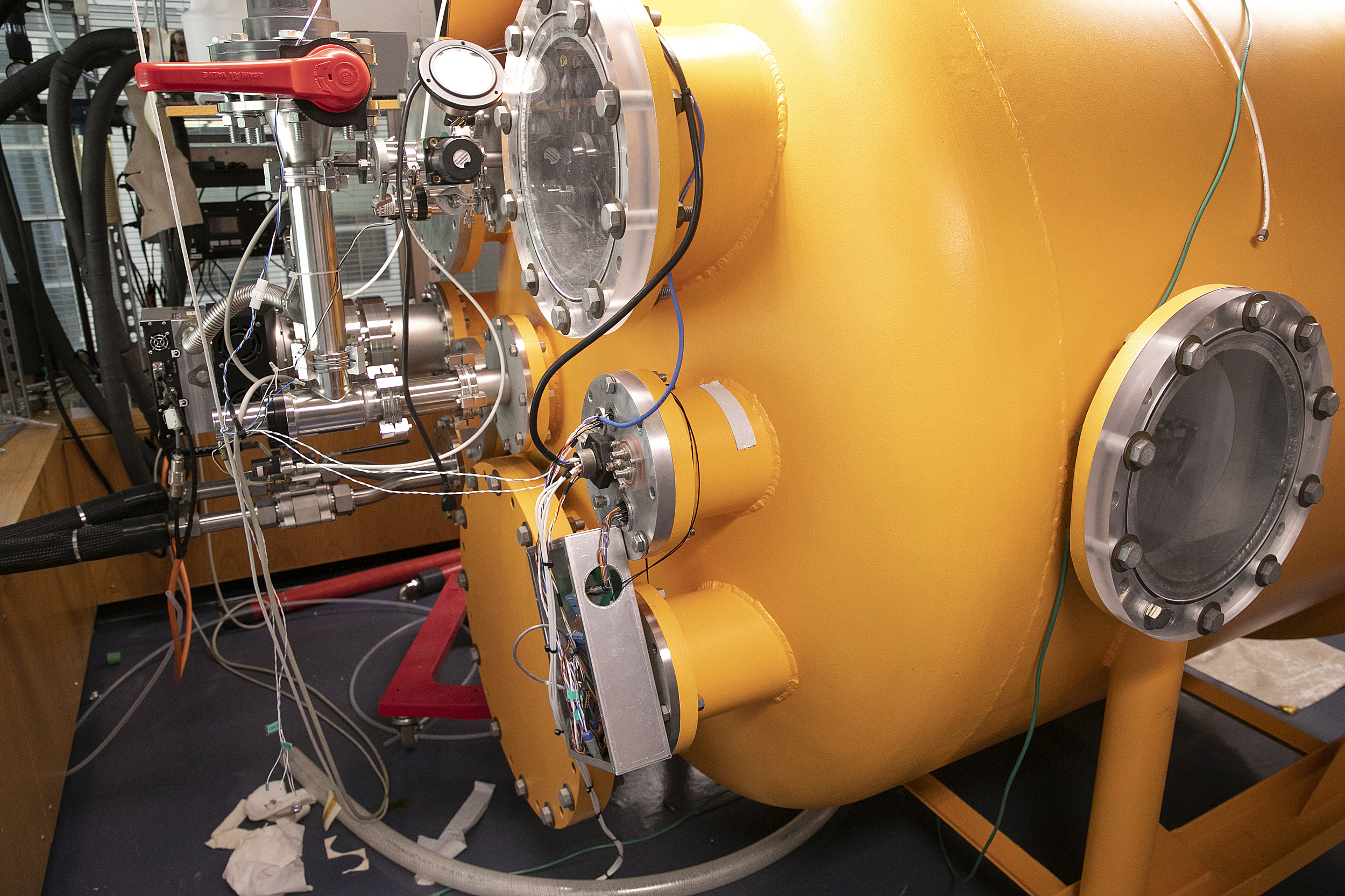

To start getting more information, the research team wants to send a remote-controlled balloon and gondola into the stratosphere somewhere above the Southwest, where the wide-open spaces and meteorological conditions should be favorable for the launch. Equipment in the gondola will spray an aerosol for a few miles, in a slowly expanding plume perhaps 600 feet in diameter, according to Keutsch. The balloon will then meander back through the spray to measure how the air and aerosol have reacted over time. The date of the test flights will be determined by an independent advisory committee that will consider not just the scientific but also the governance and social science issues involved.

The experiment, Keutsch said, is “tiny” and “will cause no climate response.” Only a few hundred grams of material will be sprayed into the stratosphere — much less than the amount a typical airplane flight emits. Despite this, his team has already faced backlash for the potential consequences of their research.

Beyond concerns about unintended environmental consequences, some organizations contend that talking about solar engineering disincentivizes people from fixing the problem, said Keutsch, “and there is some truth to that.”

And then there are those who think the experiment is just “nuts,” probably owing to its sci-fi feel, Keutsch said. Until, that is, they hear the details. “Quite often they change their opinion and say, ‘Well, I guess it’s more reasonable than I thought.’ That’s actually very common.”

The turnaround might be thanks in part to the efforts of the chemists in Keutsch’s lab, who are looking at the question of what exactly they should spray into the sky even as the engineers work out the details of the gondola. The only naturally occurring particles in the stratosphere contain water and sulfuric acid, which is produced from volcanic sulfur dioxide. But sulfuric acid is a problem because it has worrisome side effects: It cools the Earth, but it also destroys the protective ozone layer and warms the stratosphere.

The chemists think the solution could be calcium carbonate — the stuff of chalk, limestone, marble, and seashells. It may be less harmful to the ozone, and it’s not a big health concern. The team is studying how the substance affects chlorine and nitrogen oxides, which also exist in the stratosphere — largely due to man-made emissions — and speed ozone destruction. The researchers think the calcium carbonate might help to lower levels of these gases.

One thing that Keutsch wants to make clear, though, is this: Even if they are able to resolve the uncertainties and the geoengineering project is a success, it does not mean the climate change problem will have been fixed.

The reason is obvious, Keutsch said.

“It doesn’t address the cause,” he said. “So when we do this, and we keep on emitting CO2, we would have to put more and more particles in the atmosphere, and at some point that just becomes a crazy scenario, right?”

In the end, the only sustainable solution is for people to change their attitudes and behaviors. “What we have to do in any case is reduce remissions,” he said. “I think there’s no question. And that’s the basis, the starting point: We have to reduce emissions.”