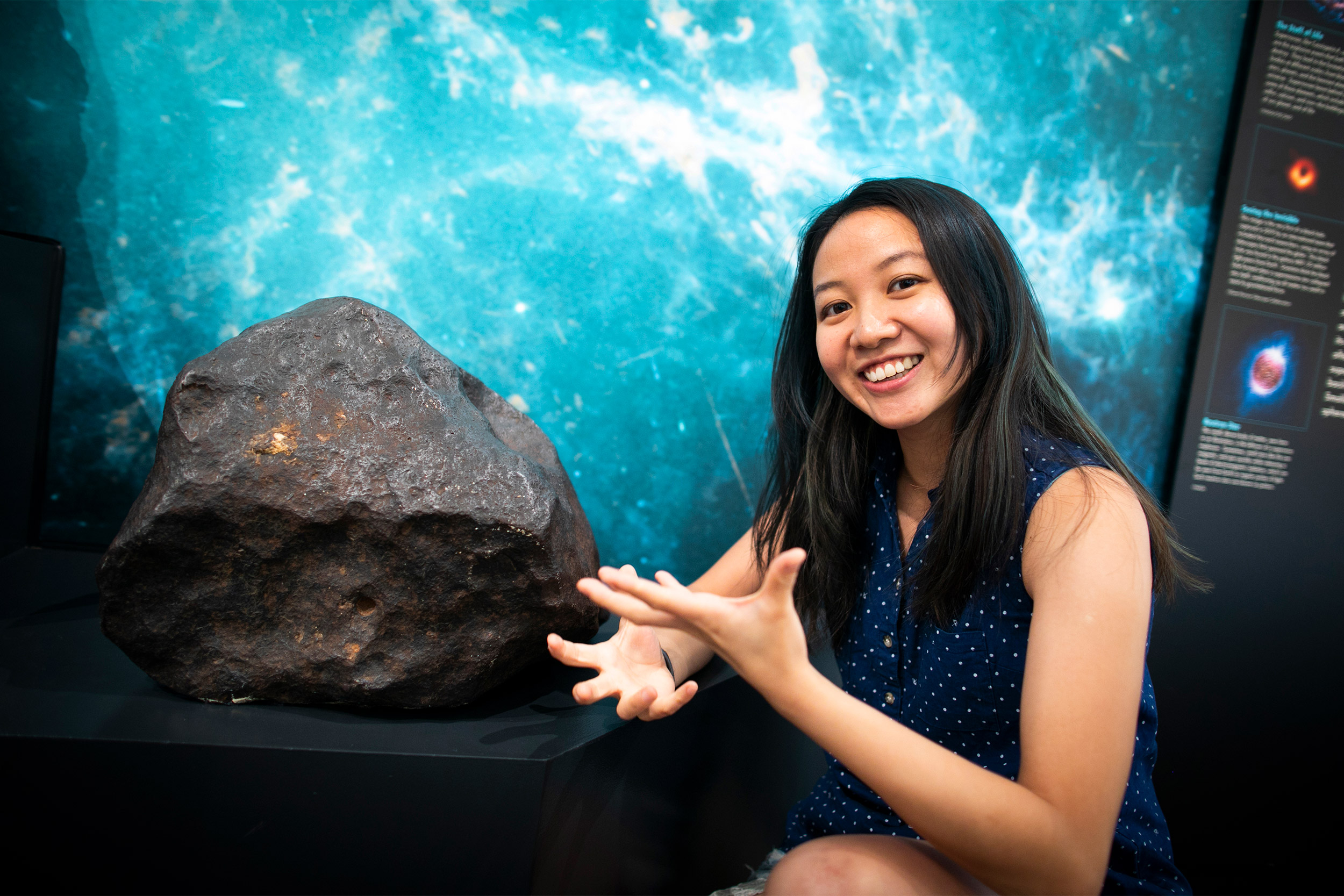

Graduate student Yaray Ku’s research focuses on how the moon was formed.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

How the moon came to be

Graduate student gets her hands on lunar samples to learn how the gleaming orb was formed

From the earliest days of human history, people have gazed at the moon and wondered: Where did it come from? What is it made of?

Growing up in Taiwan, Yaray Ku was no different. From an early age, she remembers being captivated by the gleaming orb.

But here’s the thing: She might actually be able to answer those questions eventually.

A fourth-year graduate student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences working in the lab of Professor of Geochemistry Stein Jacobsen, Ku is engaged in a project aimed at understanding how the moon formed, and to do it, she’s working with actual lunar samples.

“It’s pretty simple — I see the moon every day, and I really just wonder where it came from,” she said. “Just the simple fact that it’s there amazes me, and I think geology and planetary science is the way to really tackle those questions.”

To do it, Ku first had to get her hands on samples collected from the moon — which is easier said than done.

“We make an official proposal to NASA and ask for samples, and in most cases they send us a small vial — usually less than 100 milligrams — of what is really just powder,” she said. With sample in hand, Ku then sets out to do something that, on the surface, seems horrifyingly wrong — dissolving it with powerful acids.

“Unfortunately, the samples we work with, we have to destroy,” she said. “What we end up with is a solution that contains different elements, and because I’m only interested in certain elements — particularly potassium — I can use resins to collect those and measure their isotopic makeup.”

Ultimately, Ku said, the idea is that, by comparing the lunar material to terrestrial samples, scientists can begin to formulate a clearer idea of the aftermath of the massive collision that formed the moon.

“This goes back to the giant impact theory, which is the idea that there was a collision between the Earth and another planet, and in the aftermath the debris re-coalesced to form the moon,” she said. “Based on modeling and simulations of that collision, the prediction was that 80 percent or more of the moon came from that other planet, meaning the moon should have a different isotopic composition than the Earth.”

That was the theory, at least.

As it turned out, when researchers began to test the samples collected from the moon by Apollo astronauts, the isotopic profiles were virtually identical, forcing a re-evaluation.

Rather than the moon forming largely from the remnants of the planet that collided with Earth, the new theory was that perhaps the impact caused the two bodies to mix together, and they later separated into the Earth and moon out of a single isotopic pool.

You could be forgiven for thinking the story ends there, but a closer look at samples of Earth and moon rock found differences in some elements, particularly potassium isotopes, Ku said.

While a number of possible explanations for those differences have been advanced, none can completely explain the current measurements of potassium isotopes.

To find the answers, Ku said, researchers need to keep testing samples — particularly lunar samples.

“We more or less have pretty good estimates on the Earth rocks,” she said. “And we have lunar samples, but we only have them from a handful of places on the moon. They’re not representative. It would be great to have things from the other side, or from other locations … so we can find the best value to represent the entire moon.”

Whether she ultimately finds those answers, Ku said she is grateful to have the opportunity to work with actual material collected from the moon.

“It’s just very, very, very cool,” she said. “But more than excitement, I really feel very privileged to do this, because other people put their life on the line to go to the moon and collect [material] for our science research. So, I really do feel grateful.”

In the end, though, Ku said simply working with samples from the moon isn’t enough

“I really want to go to the moon in my lifetime,” she said. “I want to get involved in space exploration, because I feel exploring the different planets and our universe is something humans are uniquely able to do, and I want to reach for those unknowns we are chasing.”