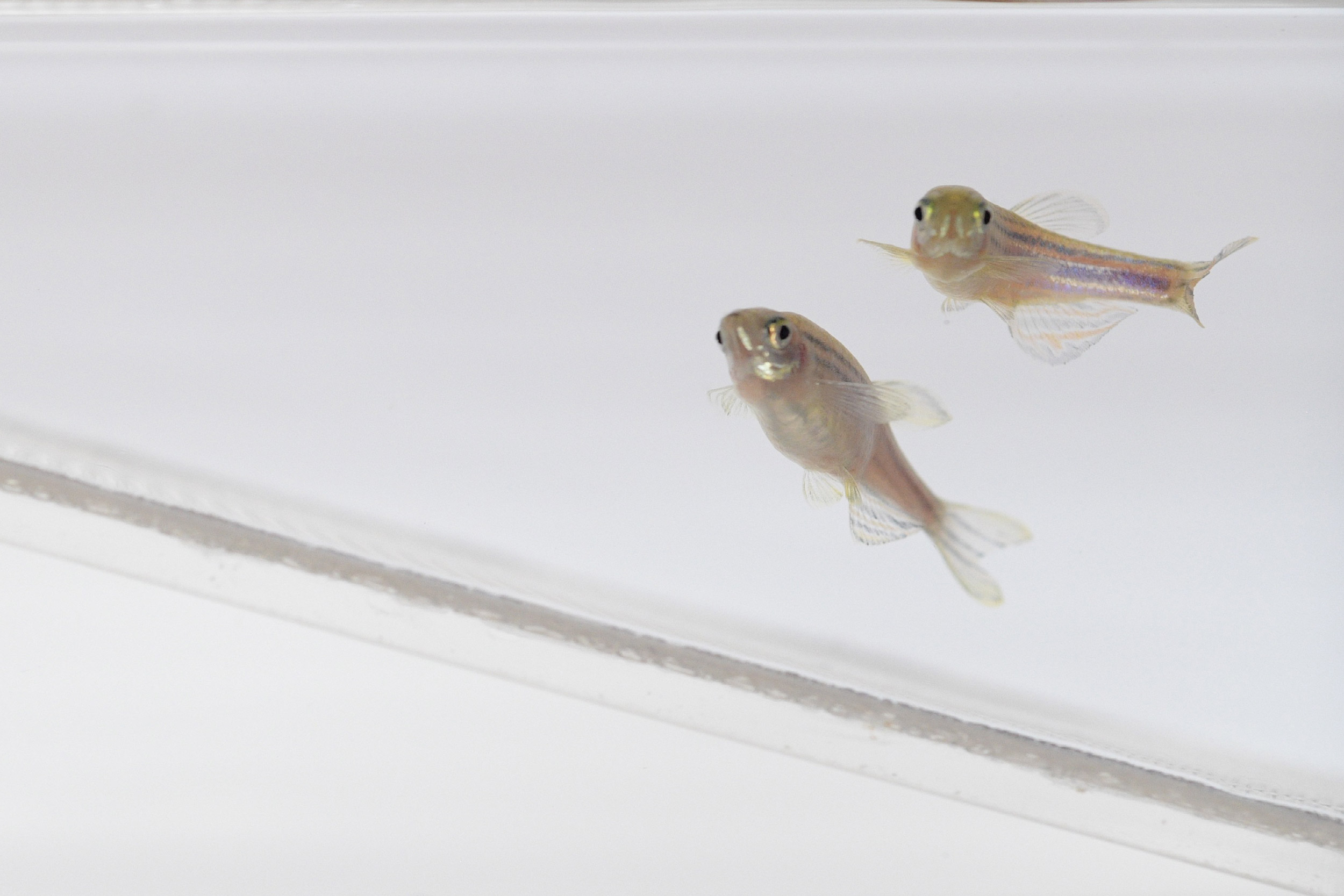

Photo by Carmen Diaz-Verdugo

How biology affects behavioral decisions

Study using brain imaging suggests why zebrafish facing a threat surprisingly opt to keep mating rather than flee

When facing a potential threat, zebrafish choose to continue mating rather than flee. This surprising response, different than that of some other species, appears to be controlled by specific brain regions that respond to pheromone cues.

These findings by scientists at Harvard University and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research (NIBR) illuminate an aspect of basic biology that will be important as researchers use zebrafish to model neurological diseases that affect social behavior, such as autism and schizophrenia. The study is published in Current Biology.

“Animals and people make behavioral decisions, ones controlled by environmental challenges and modulated by their internal drives, but little is known about the biology of these choices,” said Mark Fishman, Harvard professor of stem cell and regenerative biology and senior author of the study. “We looked at a critical decision for the survival of the species in zebrafish, giving them the choice between mating and fleeing a threat.”

To simulate a threat, the researchers used “skin extract,” a complicated mixture of pheromones that is released when a zebrafish is injured. When exposed to the substance, zebrafish usually show a strong alarm response, swimming quickly near the bottom of the tank and then freezing.

But when the zebrafish were mating, they ignored the threat. Moreover, they did not need to be mating to ignore the threat — being exposed to “mating water” that was previously conditioned by mating zebrafish was enough. This indicated to the researchers that the behavior was due to reproductive pheromones released in the water.

Microscopy captures neuron activity in different layers of the zebrafish brain.

Credit: Diaz-Verdugo and Sun et al., 2019, Current Biology

Digging deeper, the researchers used live imaging to identify specific brain regions that were activated by the mating and threat stimuli.

“When we presented both stimuli at the same time and looked at the brain, by and large we saw a response to just the reproductive stimulus, not the fear-inducing stimulus. And even further, the areas that were previously activated by the fear-inducing stimulus were now being suppressed,” said Gerald Sun, a former NIBR postdoctoral scholar and co-lead author of the study.

The zebrafish’s choice is the opposite of many other animals, including humans.

“The fish completely disregarded what is normally a very noxious, fearful stimulus, and that was really unexpected,” Sun said. “One potential explanation for why zebrafish have adopted this strategy is that they lay eggs that are externally fertilized. Humans and live-bearing fish make the opposite decision to flee a threat, because they need to survive for the next generation to be propagated.”

With a better understanding of zebrafish biology, researchers can use the animal model to study social and other behaviors.

“It’s important to establish what are the normal behaviors of zebrafish. Then you can study zebrafish as a model for diseases that affect social behavior, like autism and schizophrenia,” said Carmen Diaz-Verdugo, NIBR postdoctoral scholar and co-lead author of the study. “Once you define a well-established behavior and know the brain area responsible for it, then you can create genetic models that behave differently and use them for drug discovery.”

Although human brains are more complex than those of zebrafish, they still have a primitive component.

“We all have certain innate responses to the world around us. One hopes that with humans, you can modulate these to a certain degree. But on the other hand, your limbic system — your ‘fish brain’ — will play a big part in how you respond in different situations,” Fishman said. “We anticipate that elements of the underlying circuitry will be conserved and used for similar purposes in other species, although playing out in a species-specific manner.”

This work was funded by Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research.