Daniel Gray Wilson is the director and principal investigator of Project Zero Classroom, which was founded 23 years ago and has since drawn more than 7,000 educators from all over the world.

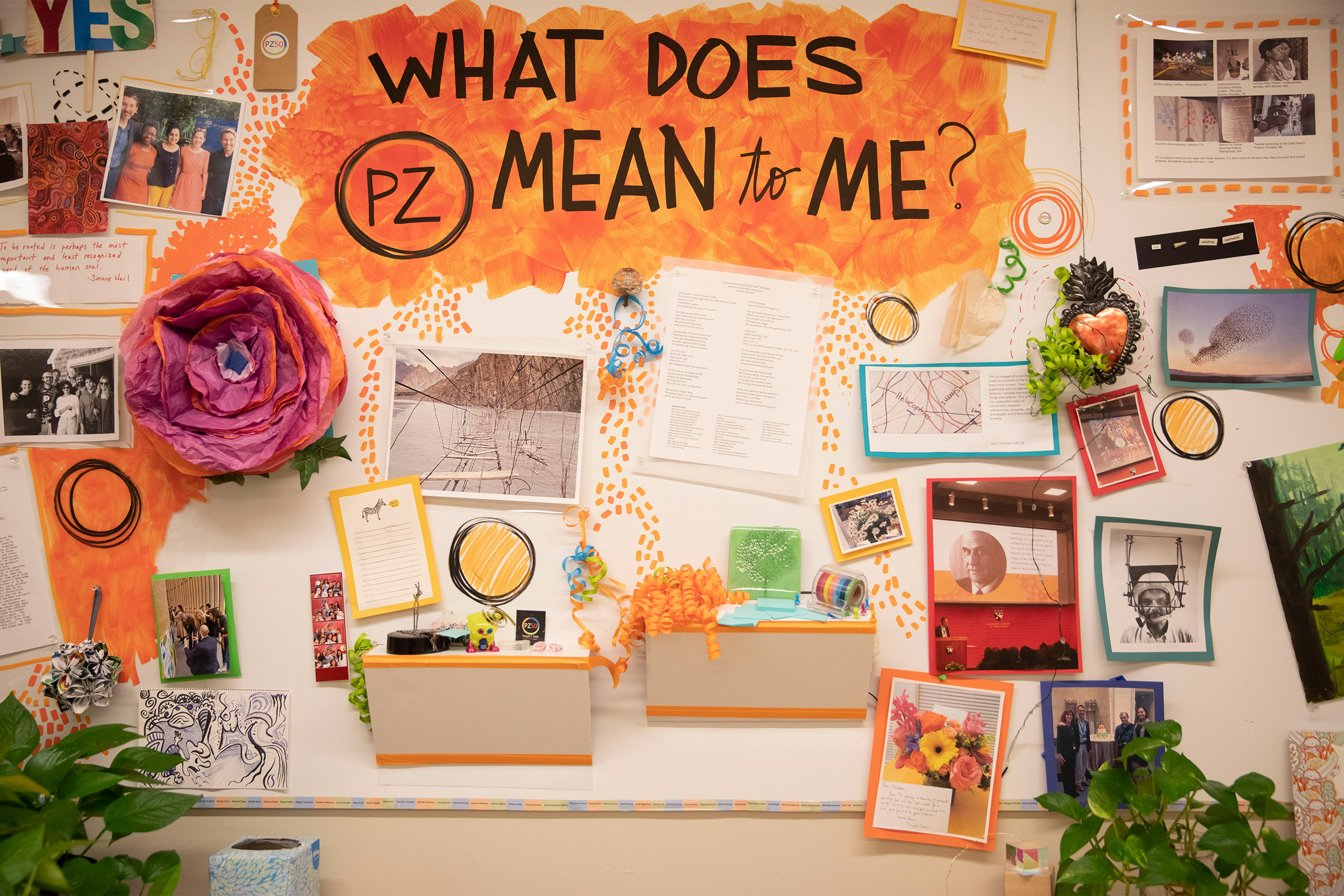

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Helping teachers learn

Conference aids educators in turning latest research into classroom innovation

Five years ago, Houston elementary school administrator Christian Stevenson Winn attended her first Project Zero Classroom, the annual summer conference at Harvard that helps teachers learn innovative educational practices and become better educators.

Winn, who is the elementary assistant principal at the T.H. Rogers School, not only learned new strategies to engage students, but she also gained a chance to reflect on her professional practice and explore dilemmas and challenges educators face in their daily work.

“Professionally, it was a life-changing experience,” said Winn, whose school is among Houston’s top 10 elementary schools. “Project Zero Classroom gives you the opportunity to develop your own questions around teaching and learning that present a challenge for you. It could be around curriculum, pedagogy, or a professional aspiration that you want to dive into to improve and grow.”

Inspired by that first conference, Winn created the Houston Learning Network to share some of the lessons learned at Project Zero Classroom. She said one of the innovations that teachers have put in practice has been to open their classrooms to colleagues so they can visit, observe, and provide feedback.

Winn will attend this year’s program as a study group leader, joining more than 360 educators who have signed up to participate. It will be held July 22‒26.

Since it was founded 23 years ago under the umbrella of Project Zero, an influential, research-based project at the Graduate School of Education (GSE), Project Zero Classroom has drawn more than 7,000 educators from all over the world.

It’s not a typical conference, said Daniel Gray Wilson, director and principal investigator of Project Zero Classroom. Participants learn about the latest research studies in the field of education conducted by more than 30 Project Zero researchers studying key questions such as how teachers can design learning experiences that unleash students’ full potential, how to help students become complex thinkers, and how schools can personalize learning for a diverse student body.

“We want to create a learning community for teachers, where they can learn about the latest educational research and learn from one another,” said Wilson. “The program operates at two levels: First there is a deep conceptual shift in the assumption about what it means for humans to learn and think, and then there’s the practical level about tools, practices, and tips they learn to support learning and thinking.”

Wilson said one of the new strategies teachers learn involves finding ways to help students move beyond rote memorization. For example, if a class is learning history, students may be asked to write a musical piece or an essay comparing a historical event to a current one.

“In today’s world, memorization is less and less important,” he said. “It’s about using that knowledge or information in responsible and critical ways. Educators are faced with the challenge of how to no longer just simply be the person who’s transmitting information and instead be the curator of a more creative application of information.”

Project Zero Classroom will bring more than 360 educators to the Graduate School of Education July 22-26.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The program has 100 faculty conducting workshops, study groups, and lectures. A key component is the small study groups in which participants discuss cutting-edge educational concepts such as teaching for better understanding, making learning visible, and developing the motivation and skills to help students think critically.

One of the goals of the small discussions is to help participants ponder strategies to put the new ideas in practice, said Wilson. “One of the key questions when they go back home is how they can support each other,” he said. “In many cases, it’ll be very hard to change the practices, the beliefs, and the cultures of schools. Often, educators come in groups so when they go home, they’re not going home alone. They’re going home with support from other colleagues.”

At T.H. Rogers School, which has sent 35 teachers and administrators to the summer program in recent years with financial support from the Harvard Club of Houston, the changes have been noticeable, said Winn. The participating teachers are always eager to practice what they learn and use their classrooms as laboratories.

In early May, Harvard President Larry Bacow met with teachers and administrators from T.H. Rogers during a tour of the southwest.

For Winn, the relationship between her school and Harvard has been instrumental. T.H. Rogers serves both gifted and multiply impaired students, including the deaf and hard of hearing, and a culturallydiverse student population of nearly 1,000, with a breakdown of 47 percent Asian, 21 percent Hispanic, 15 percent white, 13 percent African American, and 4 percent multiracial.

Most of the students are high performers, but Winn said her goal and that of her teachers is to help them become “complex thinkers in all kind of areas.” It’s a job that is never-ending, she said.

“Project Zero is a pivotal learning experience that promotes exploration, risk-taking, and the idea that you’re never there,” said Winn. “As educators, we’re always in a constant quest to find new ways to better meet the needs of the kids who sit in front of us.”