To achieve untethered flight, the latest iteration of the Robobee underwent several important changes, including the addition of a second pair of wings.

Video courtesy of the Harvard Microrobotics Lab/Harvard SEAS

The RoboBee flies solo

Cutting the power cord for the first untethered flight

In the Harvard Microrobotics Lab, decades of research culminated in a moment of stress as the tiny, groundbreaking RoboBee made its first solo flight.

Graduate student Elizabeth Farrell Helbling, Ph.D. ’19, and postdoctoral fellow Noah T. Jafferis from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, caught the moment on camera.

Helbling, who had worked on the project for six years, counted down.

“Three, two, one, go.”

The bright halogens switched on and the solar-powered RoboBee launched into the air. For a terrifying second, the tiny robot, still without onboard steering and control, careened towards the lights.

Off camera, Helbling exclaimed and cut the power. The RoboBee fell dead out of the air, caught by its Kevlar safety harness.

“That went really close to me,” Helbling said, with a nervous laugh.

“It went up,” Jafferis, who had also worked on the project for about six years, responded excitedly from the high-speed camera monitor where he was recording the test.

And with that, Harvard University’s Robobee became the lightest vehicle ever to achieve sustained untethered flight.

The August 2018 milestone is described in today’s issue of Nature.

“This is a result several decades in the making,” said Robert Wood, Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at SEAS, core faculty member of the Wyss Institute, and principle investigator of the RoboBee project. “Powering flight is something of a Catch-22 as the trade-off between mass and power becomes extremely problematic at small scales where flight is inherently inefficient. It doesn’t help that even the smallest commercially available batteries weigh much more than the robot. We have developed strategies to address this challenge by increasing vehicle efficiency, creating extremely lightweight power circuits, and integrating high-efficiency solar cells.”

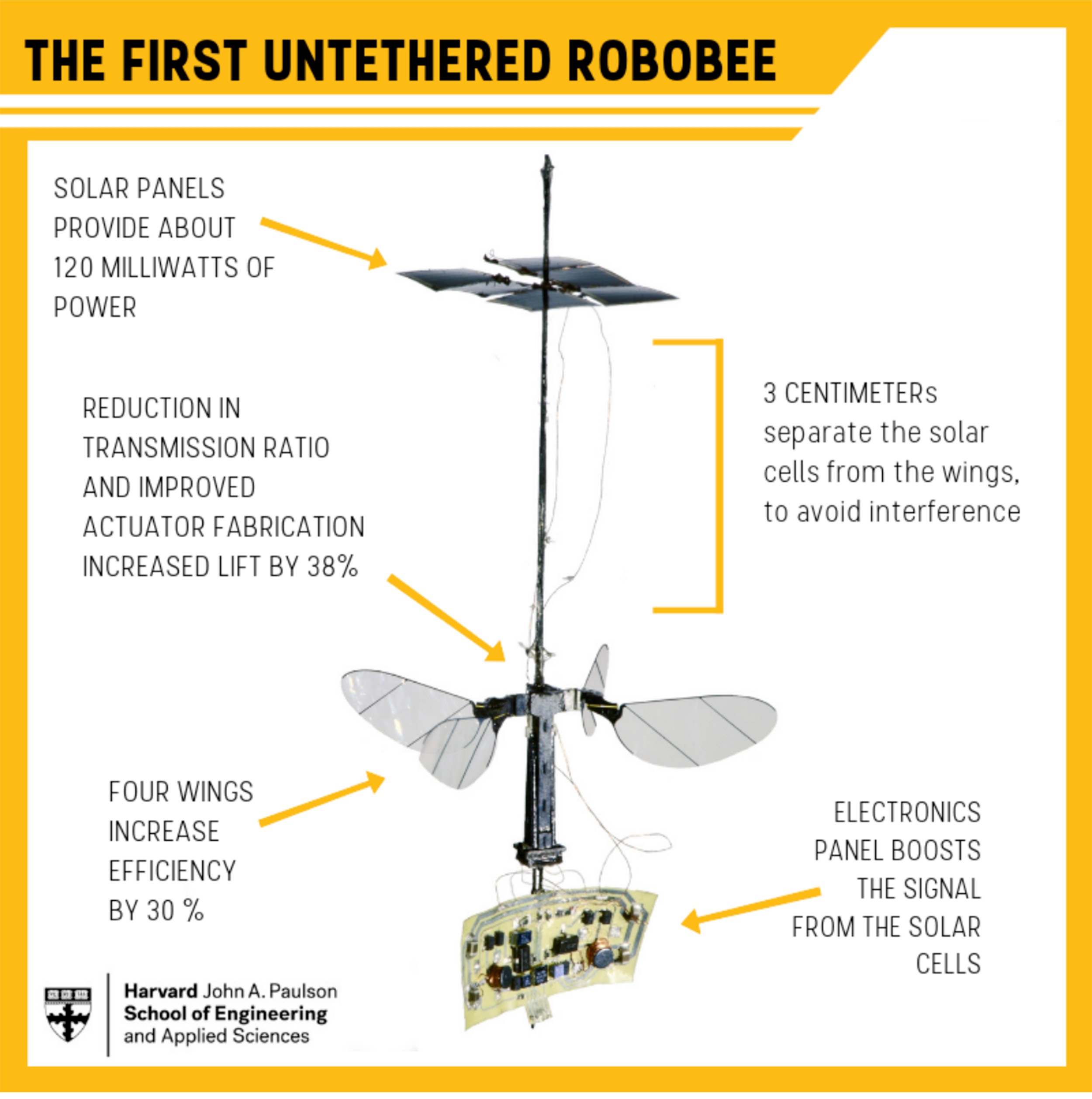

To achieve untethered flight, this latest iteration of the RoboBee underwent several important changes, including the addition of a second pair of wings.

“The change from two to four wings, along with less-visible changes to the actuator and transmission ratio, made the vehicle more efficient, gave it more lift, and allowed us to put everything we need on board without using more power,” said Jafferis.

The addition of the wings also earned this RoboBee the nickname X-Wing, after the four-winged starfighters from “Star Wars.”

That extra lift, with no additional power requirements, allowed the researchers to cut the power cord — which had kept the RoboBee tethered for nearly a decade — and attach solar cells and an electronics panel to the vehicle.

The solar cells, the smallest commercially available, weigh 10 milligrams each and get 0.76 milliwatts per milligram of power when the sun is at full intensity. The RoboBee X-Wing needs the power of about three Earth suns to fly, making outdoor flight out of reach for now. Instead, the researchers simulate that level of sunlight in the lab with halogen lights.

The solar cells are connected to an electronics panel under the bee, which converts the low-voltage signals of the solar array into high-voltage drive signals needed to control the actuators. The solar cells sit about three centimeters above the wings, to avoid interference.

In all, the final vehicle, with the solar cells and electronics, weighs 259 milligrams (about a quarter of a paper clip) and uses about 120 milliwatts of power, which is less power than it would take to light a single bulb on a string of LED Christmas lights.

“When you see engineering in movies, if something doesn’t work, people hack at it once or twice and suddenly it works. Real science isn’t like that,” said Helbling. “We hacked at this problem in every which way to finally achieve what we did. In the end, it’s pretty thrilling.”

The researchers will continue to hack away, aiming to bring down the power and add onboard control to enable the RoboBee to fly outside.

“Over the life of this project we have sequentially developed solutions to challenging problems, like how to build complex devices at millimeter scales, how to create high-performance millimeter-scale artificial muscles, bioinspired designs, and novel sensors, and flight-control strategies,” said Wood. “Now that power solutions are emerging, the next step is onboard control. Beyond these robots, we are excited that these underlying technologies are finding applications in other areas, such as minimally invasive surgical devices, wearable sensors, assistive robots, and haptic communication devices — to name just a few.”

Harvard has developed a portfolio of intellectual property (IP) related to the fabrication process for millimeter-scale devices. This IP, as well as related technologies, can be applied to microrobotics, medical devices, consumer electronics, and a wide range of complex electromechanical systems. Harvard’s Office of Technology Development is exploring opportunities for commercial impact in these fields.

This research was co-authored by Michael Karpelson. It was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research.