iStock

Pharma-to-doc marketing a vulnerability in opioid fight

Harvard-Michigan summit on issue explores addiction, policy

Pharmaceutical companies’ television ads have come under fire for pitching drugs to consumers, but another marketing tactic, behind closed doors and often ignored, is perhaps even more troubling, according to one expert.

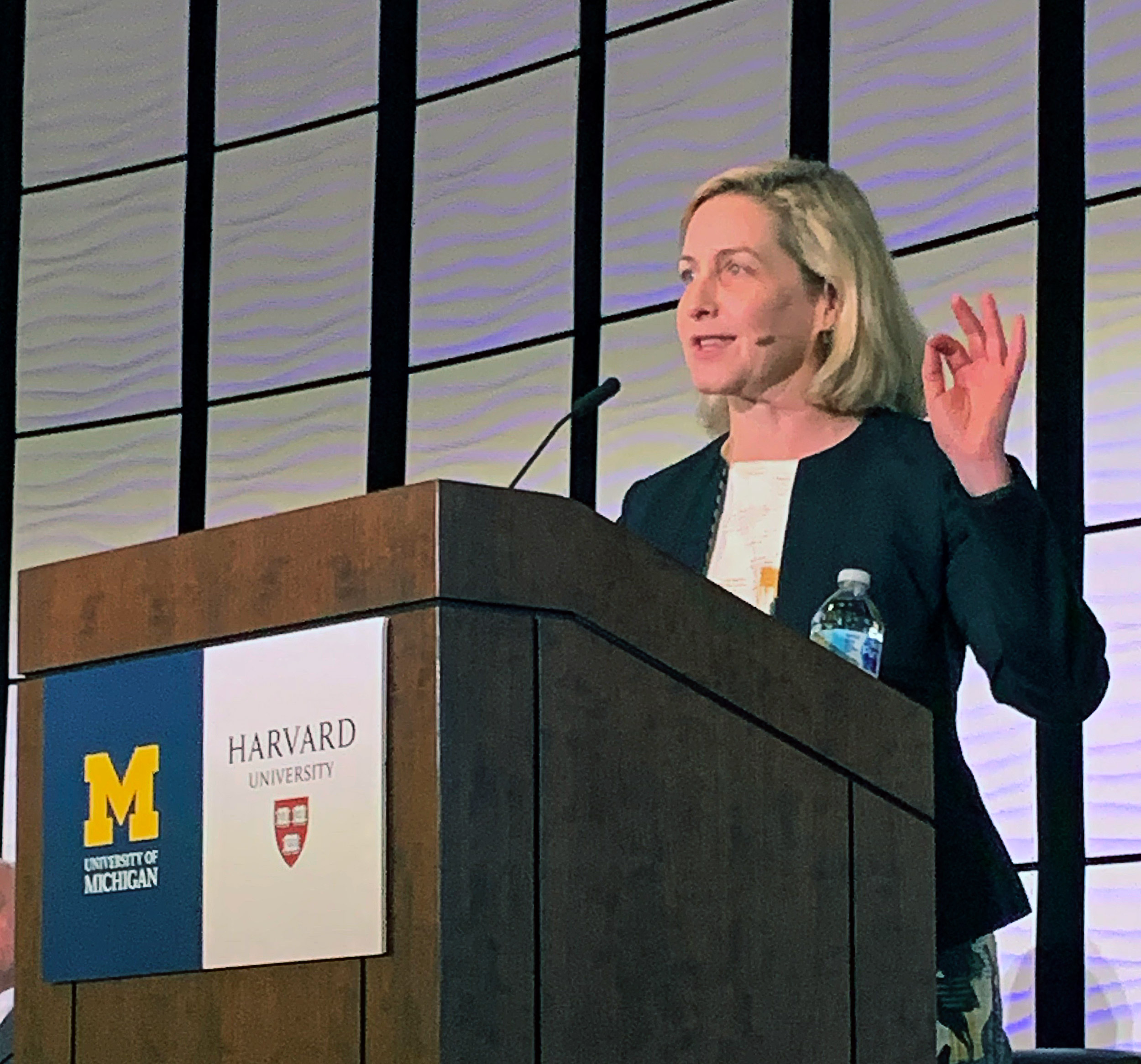

Harvard health economist Meredith Rosenthal said drug companies also pitch their wares directly to doctors through an array of tactics, including face-to-face marketing, in a little-scrutinized process that may be ripe for regulation.

“What goes on behind closed doors might require a totally different approach,” Rosenthal said.

Rosenthal cited a 2019 study that showed that, though direct-to-consumer advertising grew most rapidly — more than fourfold, to $9.6 billion — between 1997 and 2016 that total was dwarfed by the $20.3 billion the industry spent marketing to physicians. Included in that total were direct payments to doctors for things such as speaking fees, free samples, face-to-face pitches by drug company representatives, and disease education efforts.

Rosenthal, the C. Boyden Gray Professor of Health Economics and Policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said though physicians claim they aren’t influenced by sales visits, recent studies showed that doctors’ attitudes toward the drugs more closely echo pharmaceutical company pitches than the findings of published scientific studies.

“Pharmaceutical marketing … is ubiquitous,” Rosenthal said. “Studies have shown that despite physicians denying relying on pharmaceutical messaging, attitudes are closer to that than to scientific evidence.”

Rosenthal made her comments during an all-day conference focused on the opioid epidemic. Called “Opioids: Policy to Practice,” the event was co-sponsored by Harvard and the University of Michigan.

Held in Ypsilanti, Mich., the conference was the first of two examining the issue. Billed as a “University of Michigan ‒ Harvard University Summit,” the event stemmed from an agreement last fall between the two universities that the Harvard Chan School and the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network would collaborate to find scalable solutions to the opioid epidemic.

The second summit will be held next October at Harvard. The collaboration on the opioid epidemic was just one of two partnerships between the universities struck in the fall. The second, focused on boosting economic opportunity in Detroit, pairs Harvard’s Equality of Opportunity Project and the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions initiative, the city of Detroit, and community partners.

The opioid summit, held May 10, featured Harvard and University of Michigan experts, as well as authorities from a variety of outside organizations. University of Michigan President Mark Schlissel and Chad Brummett, co-director of the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network, delivered opening remarks.

Brummett and Mary Bassett, the Francios-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights and director of the Harvard Chan School’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, co-chaired the event. Bassett, the former commissioner of health for New York City, spoke on a panel discussing the public health response from urban to rural communities. Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard Chan School, participated on a panel discussing health systems approaches to opioid prescribing.

Barbara McQuade, a professor from practice at the University of Michigan Law School, said the conference represented exactly the kind of collaboration between an array of fields that’s needed to solve the problem.

McQuade cautioned that interventions and public policies should be carefully considered so they don’t have unintended consequences like those that occurred when cracking down on prescription drug abuse pushed addicts to more dangerous heroin and fentanyl.

Craig Summers, executive director of the Michigan High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a federal grant program to coordinate law enforcement anti-drug efforts, said that access to real-time data about overdoses and deaths will improve law enforcement’s ability to fight drug traffickers. Timely data, he said, means the difference between getting a fentanyl dealer off the street when overdoses are first detected and waiting until several deaths occur.

Traffickers, Summers said, aren’t interested in the epidemic’s human toll — they’re only interested in making money, and will fill a demand wherever it is. That means prevention efforts and programs to reach young children with anti-drug messages are critical. Summers also said that, though the focus is on opioids, large amounts of cocaine and methamphetamine are also coming into the state.

“The cartels have one objective and one objective only: to make money,” Summers said. “They have no regard for human life. If there’s a demand, they will find a way to serve it.”

In addition to talks by academic experts and leaders from the epidemic’s front lines, the event included comments by David Clayton, outreach coordinator for Families Against Narcotics. Clayton shared his personal experience with addiction and said that his life shows what a difference effective treatment can make. He has been clean and sober since 2013.

Clayton grew up in a stable household, an athlete and a good student. He became addicted to prescription painkillers at age 18 and doctor-shopped to get the drugs, visiting up to five doctors, until he was found out and cut off. By age 21, estranged from his family, he sniffed heroin for the first time. At 24, he became an intravenous drug user.

Clayton recalled one occasion when he agreed to go to rehab. As he waited to leave, he rummaged through boxes of his belongings in his parents’ basement looking for leftover drugs to ease his withdrawal, and came across funeral prayer cards with his name on them, evidence that his mother was planning his funeral. Instead of rehab, he crawled out of the basement window and left.

In September 2013, intent on killing himself with drugs, he got arrested instead. He was sent to treatment and then to a “sober house” to live. Instead of dying that day, he said, he got his life back. Today, he owns a house and works traveling the state to fight addiction.

“Recovery is possible,” Clayton said. “Sept. 23, 2013, I wanted to end my life. It was the last day I had to use drugs and alcohol. It was the last day drugs and alcohol told me when to wake up and when to sleep.”