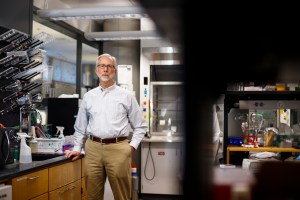

Nainoa Thompson, President of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and a Pwo navigator, shared his views on climate change from the perspective of indigenous peoples at the Divinity School.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Putting ‘the language of the Earth on the agenda’

Indigenous leaders offer unique perspective on climate change

Climate change may finally be making headlines, but it is far from news. Addressing an overflow crowd at “The Land and the Waters Are Speaking: Indigenous Views on Climate Change” at Andover Hall on Thursday evening, Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq, an Eskimo Kalaallit elder and storyteller, recalled hearing of the first warning signs back in 1963.

The occasion was a traditional ceremony in which hunters in Greenland go inland to the glacier — the “big ice” — to give thanks.“ And they looked up there and water was trickling down,” said Angakkorsuaq. “The big ice was dripping water.” This was in January, when the temperature averaged 35 degrees below zero Celsius, a hard freeze that would typically last for three months. When a group of elders repeated the ceremony that March, they found the same stream. What they would eventually learn was that rising temperatures were creating lakes on top of the glacier, and that water was seeping down through cracks, accelerating further melting.

Angakkorsuaq, now 72, later became a runner for the elders, spreading news from village to village. It was with that mission that in 1978 he was sent to address the United Nations, where he spoke of the increasing melt. In a folksy, often humorous style, the silver-haired storyteller known as “Uncle” described being in the city, in a three-piece suit, and returning to tell his community about his triumph.

“Then all of a sudden, my beloved father stopped me and said, ‘Did they hear you?’ I said, ‘They gave me a standing ovation!’ And then he asked again, ‘Did they hear you?’ And he wanted to know if they heard my message from the elders: The ice is melting and it’s not good for the Earth and the people who live on her and the animals who live on her and the plants who live on her.”

Angakkorsuaq repeatedly drew the connection between the spiritual and the physical, linking kindness and love with stewardship of the Earth. “It’s too late to stop the melt of the big ice,” he said, frequently returning to this ominous note. “The ice will melt and the ocean will rise, and many of our families will lose their land. Boston will be under water. Where should we put you? Who should take care of you?”

Speaking earlier at the event — part of the Constellation Project, co-sponsored by the Planetary Health Alliance, the Harvard Divinity School, the Center for the Study of World Religions, the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Harvard College Hawaii Club — Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, shared his stories of sailing the ocean in a double-hulled canoe. For Thompson,the first Native Hawaiian in 600 years to practice the ancient Hawaiian art of navigation using only the stars, the wind, and the flight of birds, the ecological is also deeply personal. In particular, it is linked to his heritage.

Nainoa Thompson, left, and Shaman Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq (Uncle), an Eskimo Kalaallit Elder, shared their perspectives on climate change.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hawaii, Thompson recalled, was thriving when England’s Capt. James Cook landed there in 1778. He cited Cook’s descriptions of “a healthy people, a very strong people, with high art forms.” The Hawaiians had achieved what Thompson called “a thing called sustainability. They had to. One hundred percent of what kept them alive came from the island.”

However, with European incursion, things began to change. “Twenty-eight years after the European discovery of the island, 79 percentof native islanders had died,” he said, calling it “the chronic story of what happens to indigenous people around the world.”

“It’s characterized by the loss of everything: your lands, governance,” he said. “When you get close to extinction is when they take away your dignity.”

This didn’t begin to turn around until the 1970s, when, with the help of anthropologists such as the late Californian Ben Finney, Hawaiians began to believe again that they had been great navigators. The path to proving this — and to reasserting self-esteem — would be to build an ocean going canoe and navigate it from Hawaii to Tahiti using traditional methods. The only problem, explained Thompson, was, “None of us knew anything about our culture. It wasn’t valued enough.”

The islands of Micronesia, smaller and less valuable to the Europeans, still had six master navigators. The youngest of these, Pius “Mau” Piailug, was approached. It was a big ask. To complete the proposed journey, explained Thompson, “He’d cross the equator and see stars he’d never seen on a canoe he hadn’t constructed with a crew he hadn’t selected. When Hawaii came and asked, he knew if we failed, then all we would have done was meet the expectation that we would fail because we were Hawaiian. So he came and he saved us.”

Thompson, who crewed on the return trip, describes himself and his colleagues as rank amateurs who ran aground on sandbars as they started to learn the ways of their ancestors. “Everything changed after that,” he said. Even teaching in Hawaiian, which had been banned in 1896, has now been restored, with K–12 Hawaiian culture, language, and study programs. “We could believe again.”

The move to that lost sustainability is a continuation of this growth, and today Thompson is a master navigator himself. Having circumnavigated the globe, he is now planning a trip around the Pacific, highlighting the damage we are doing to our oceans and way they connect us all. “We’re going to put the language of the Earth on the agenda,” he said.