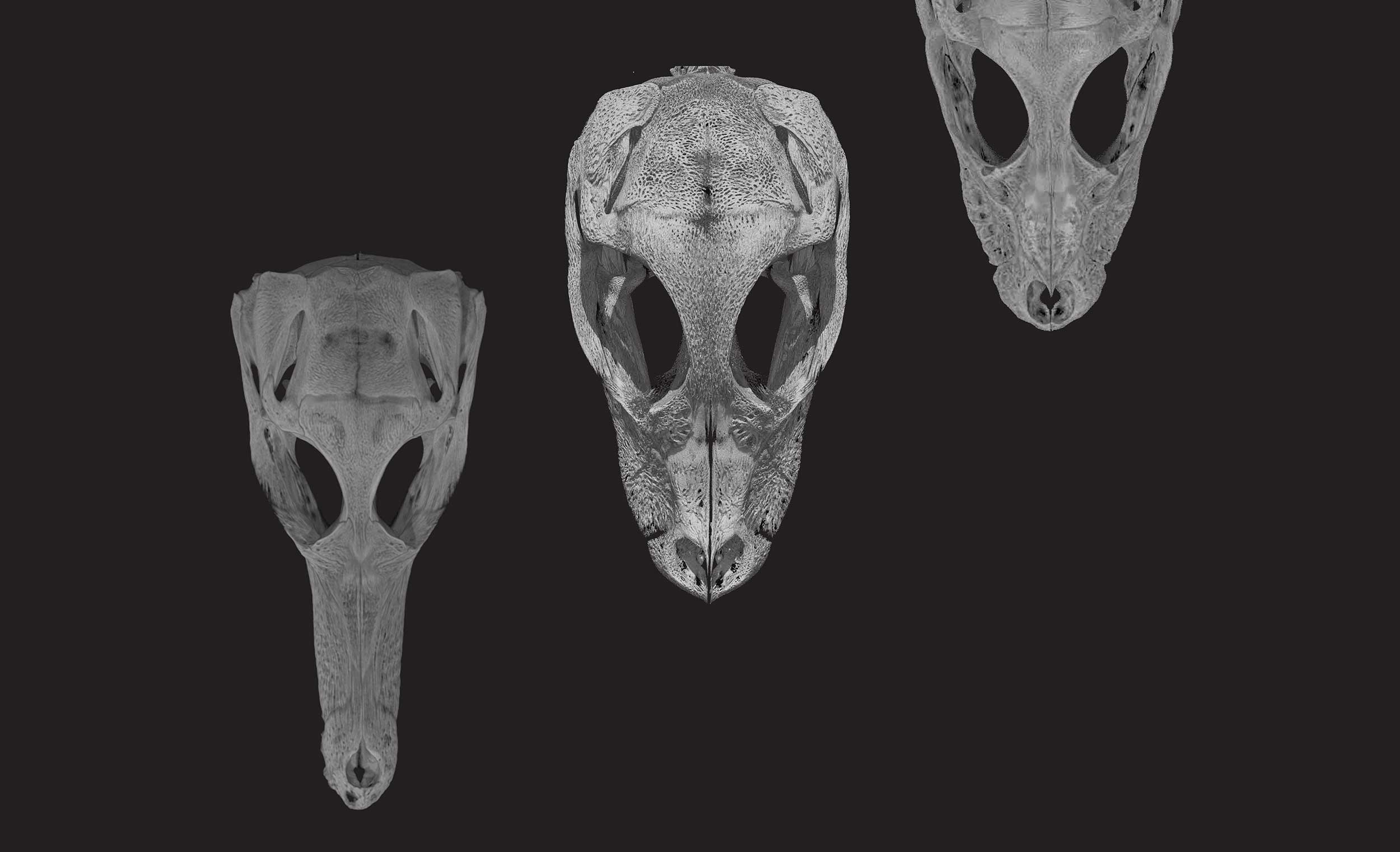

CT scans of embryonic skulls of the dwarf African crocodile, American alligator, and false gharial. Research demonstrates that the diversity of skull shapes found today is the result of a “very flexible developmental tool kit.”

Courtesy of Zachary S. Morris

Facing crocodiles head-on

Study examines how evolution modified the long-surviving reptiles’ snouts

The story that’s often told about crocodiles is that they’re among the most perfectly adapted creatures on the planet — living fossils that have remained virtually unchanged for millions of years.

The reality is far more interesting.

Throughout their evolutionary history, crocodiles, alligators, and their kin have repeatedly evolved similar skull shapes in response to dietary specializations: long snouts for eating fish; short snouts for harder prey; and moderate snouts for large prey. But how is such broadscale convergence generated?

Research led by Stephanie Pierce, associate professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and Zachary Morris, Ph.D. ’20, aims to tackle this question by comparing embryonic development with later growth in all species of living crocodiles. Their work demonstrates that the diversity of skull shapes found today was realized by altering developmental patterns during evolution. The study is described in a Feb. 20 paper published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The work was done in collaboration with Arkhat Abzhanov at Imperial College London and Kent Vliet at the University of Florida.

“This study is just a snapshot of crocodile evolution,” Pierce said. “But it shows they have been tinkering with their developmental strategy in order to adapt to their environment, so they can be as successful as possible.”

Stephanie Pierce and Zachary Morris are the co-authors of a new study that looks at the evolution of crocodile skulls. They are pictured at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

That success, Pierce and Morris said, is due in part to their surprising plasticity.

“Crocodiles are often thought to be unchanged by time, but our analysis instead suggests that they have evolved a very flexible developmental tool kit,” Morris said. “So given enough time and selective pressure they are able to alter the rate and timing of development, resulting in ecologically different forms with long, short, and moderate snout shapes.”

And importantly, Morris said, those general shapes aren’t limited to living crocodiles. They have evolved independently multiple times in the fossil record.

“There’s a great deal of convergence that wasn’t initially appreciated,” Pierce said. “In the past, the shape of the skull was used to assign evolutionary relationships, so if an animal was short-snouted, it was [thought to be] related to all the other short-snouted species. But with modern analyses, we’ve been able to determine that many of the animals that have similarly shaped snouts are actually not related to one another. The independent acquisition of the same snout shape is presumably due to having similar ecological pressures, such as eating similar foods.”

Whatever those pressures are, Morris said, the similarities in adult skull shapes must be underpinned by changes in the developmental patterning and growth of the skull.

“We know, in a general sense, that an important part of what makes an alligator different from a gharial or a dwarf African crocodile has to do with changes to ontogeny, or the embryonic development and post-hatching growth,” Morris said. “Given that these different forms have evolved independently multiple times, we have the opportunity to see whether there are fundamental mechanisms underlying the evolution of those shapes.”

Essentially, Pierce said, that was the question she and Morris set out to answer in the paper — whether the ontogenetic paths various crocodile species take to achieve their adult forms are similar to or different from one another. “What we’re trying to understand,” she said, “is how crocodiles do it — how do they converge, as adults, on these same shapes? Are they doing it very early in embryonic development or does it happen later on?”

To get at those questions, Morris CT scanned dozens of crocodile embryos, photographed post-hatching specimens held in museums around the globe, and digitized anatomical coordinates on each skull at specific locations so he could track how their shapes changed through development.

“It was not a trivial thing to sort out how to do this,” he said, “because in the very youngest embryonic specimens, they only have very tiny, thin splints of bone.”

Eventually, Morris was able to identify “landmarks,” or identifiable points, for every specimen and track how those changed throughout their development as embryos and into adulthood.

“One of the really interesting results we found is that, with the exception of two of the most extreme short-snouted forms, all other crocodiles start from the same embryonic starting point,” Morris said. “They’re able to make, as adults, a huge range of functionally different shapes from this same starting point.”

And while most crocodiles take very similar paths to get to their adult shape, the study found others take radically different ones.

“What we found was that the ontogenetic trajectories of short forms are essentially identical to each other,” Morris said. “But that’s not true for the long-snouted forms. They have very similar adult shapes, but they have very, very different ways of getting there.”

Pierce and Morris took their analysis one step further. They used the ontogenetic trajectories of living crocs to backtrack through time to investigate the developmental pattern of the last common ancestor of modern crocodiles.

“We have data for how these living animals develop,” Pierce said, “so we thought, ‘Based on their evolutionary relationships, let’s reconstruct how their ancestor developed.’ And then let’s use that to understand how the living animals acquired their ontogenetic trajectories … and how they went about slightly changing their developmental strategy to eventually end up with their long or short snouts.”

“We were able to show that short-snouted species slowed down their development from the ancestral crocodile in similar ways, while long-snouted species either sped up development or started off with much longer snouts as embryos,” said Stephanie Pierce. Pictured are false gharial and Cuvier’s dwarf caiman crocodiles.

Photos by Zachary S. Morris

What that analysis showed, Morris said, was that the ancestral crocodile was likely moderate-snouted, similar to the generalist crocodiles found today.

“So what’s really interesting is if the ancestral trajectory is similar to the generalized crocodiles, then somewhere along the evolutionary branches leading to the short and long forms there must have been changes in the developmental pattern,” Morris said.

“Excitingly,” Pierce continued, “We were able to show that short-snouted species slowed down their development from the ancestral crocodile in similar ways, while long-snouted species either sped up development or started off with much longer snouts as embryos. Essentially, slightly dialing up or down the rate and timing of development during evolution resulted in the diversity of skull shapes we see today.”

Going forward, Pierce and Morris plan to expand their research as part of an effort to understand the evolution of the entire crocodilian line, and to continue studying embryonic development in modern crocodiles with the goal of identifying the genetic cues that underlie changes in skull shape.

“It was important to establish how modern crocodiles generate their skull shapes embryonically, so we can extrapolate from them and make comparisons with the patterns we see in the fossil record,” Morris said. “But we also want to see if we can tie these changes to a specific genetic mechanism, so we can then understand the broader evolutionary mechanisms that give rise to these kinds of convergent patterns.”

This research was supported with funding from the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s Wood Award, and the National Science Foundation.