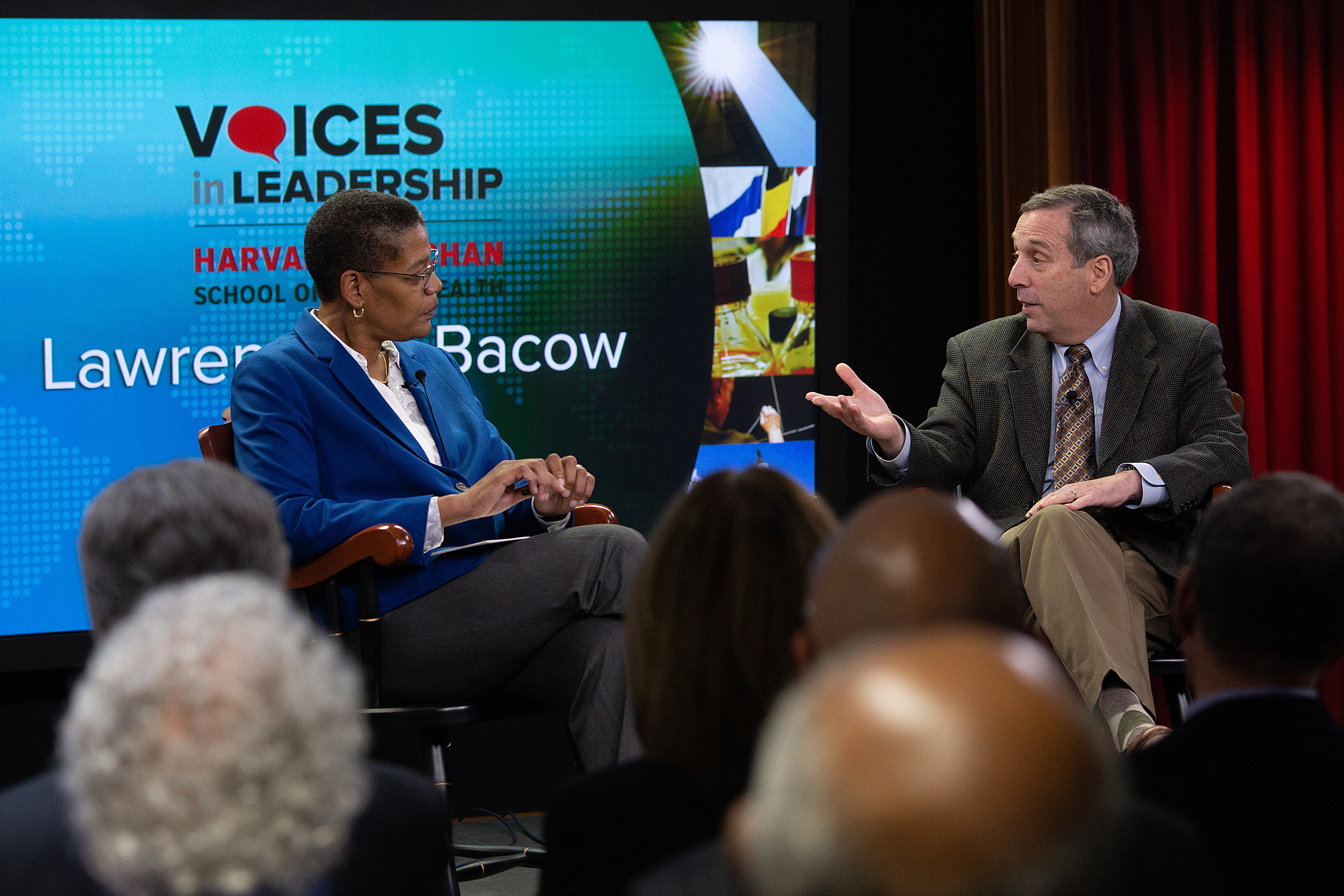

President Larry Bacow shared his views on leadership with Michelle Williams, dean of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Sarah Sholes/Harvard Chan School

Leadership lessons from Harvard’s president

Bacow suggests: ‘Surround yourself with good people, and help them achieve’

Do the right thing, even when it’s hard. Invest in the success of those around you. And never underestimate the persuasive power of reframing controversial questions.

Those were the take-home messages Wednesday from Harvard President Larry Bacow, who, despite having led both Harvard and Tufts and having been MIT’s chancellor, said he still considers himself something of an “accidental president.”

Bacow, who appeared on a webcast of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Voices in Leadership program, responded to questions from Chan School Dean Michelle Williams that spanned everything from his personal experience of leadership to controversies and challenges along the way to tips for students who hope to lead someday.

Bacow said he claims the “accidental” mantle because for the first two decades of his career on MIT’s faculty he studiously avoided the leadership ladder, happily focusing on his research and teaching.

That ended when he was asked to become MIT’s dean of faculty. Bacow felt he couldn’t turn the appointment down because he saw it as helping his faculty colleagues. When he left that post he returned to his faculty duties for only a short time before he was tapped to be MIT’s chancellor, another position he viewed as service to the institution where he’d been — except for graduate work at Harvard — since his undergraduate days.

The chancellorship raised Bacow’s visibility and brought offers for several open positions as university president, most of which he turned down. That process highlighted for him, he said, that some of the best career decisions are jobs you don’t take. There are some simply bad jobs out there, he said, as well as jobs that would be a poor match, or are badly timed, or might not point you where you want to go in life.

“I didn’t think I wanted to be a university president. I liked doing what I was doing,” Bacow said. “When I talk to people who are thinking of taking a job like this, I say, ‘Ask yourself what you want to get done. Take a job because you have an agenda, not because the job is just there.’”

A leader should approach a new organization with the same mindset as a cultural anthropologist, as someone who doesn’t speak the local language and is ignorant of everyday life there, Bacow said. As an example, he joked that both decentralized Harvard and top-down MIT have reputations for excellence, yet “organizationally and culturally, they’re identical — only with a sign change.”

Their differing cultures, Bacow said, illustrate that there isn’t just one path to success, an important thing for leaders to recognize.

A leader should approach a new organization with the same mindset as a cultural anthropologist, as someone who doesn’t speak the local language and is ignorant of everyday life there, Bacow said.

Sarah Sholes/Harvard Chan School

“That just speaks to the fact that there’s more than one way to organize an institution,” Bacow said. “And you just need to be cognizant of … the traditions and what people know and understand and are comfortable with. And [think about] how do you get them to understand that there might in fact be something different?”

He suggested that one way to be an effective leader is to “surround yourself with good people, and really help them achieve what they would want to do.”

Bacow called the current times “interesting and challenging” for higher education. He said he can’t recall another period when people questioned whether sending their children to college was worth the cost, when lawmakers doubted universities’ motives enough to tax them despite their nonprofit status, and when segments of society wondered whether higher education was still a force for good in the country.

“My highest priority is to try to change this narrative about higher education,” Bacow said. “I think that people are casting a critical eye to institutions like Harvard … because they think that we’re elitist. They think we’re far more concerned about making ourselves great than the world better. They think that we’re incapable of controlling our own costs, [and] there’s a lot of public anger at just the breathtakingly expensive cost of college education these days. And then I think there’s concerns over whether institutions like ours are as truly open to new ideas or ideas from across the ideological spectrum as we claim to be.”

Despite those questions, Harvard graduates have a long history of service to the country, Bacow said, as evidenced at the highest levels by the number of presidents and Supreme Court justices among its alumni. In the current Congress alone, 14 graduates are serving in the Senate, and more than 40 in the House.

The opportunity to participate in service, Bacow said, should include all students. At a time when the University is working to ensure that a larger portion of its student body is drawn from families with lower means, it’s important that students who have to think hard about giving up summer jobs for unpaid internships, travel, or volunteer posts are able to take advantage of those opportunities.

Another challenge, Bacow said, has been the court fight over campus diversity. The University’s current case, Bacow said, shows the power of reframing a question, particularly a controversial one. The president said when he is asked about the lawsuit, he highlights the importance of diversity in a College education and how dull the campus would be if everyone came from the same place, studied the same thing, embraced the same extracurriculars, and had the same career goals.

“It would be a far less interesting place if that were true,” Bacow said. “We learn from our differences.”

He said he also asks questions intended to shift his inquisitors’ perspectives. The suit argues that students should be admitted based largely on test scores and academic qualifications, so he asks how many in the room would ever hire someone purely on the basis of grades, without an interview, without checking references, and without checking work products.

“The answer is all of us are more than our grades and our board scores,” Bacow said. “Leadership involves framing, but it also involves teaching and helping people to understand and see issues from your perspective.”