The Arboretum’s collection makes studying the comparative biology of trees near effortless. A weeping katsura tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum ‘Mokioka Weeping, pictured) grows just meters away from the typical, upright form, allowing a scientist the easiest of access to contrast them.

Photo courtesy of the Arnold Arboretum/Harvard University

A growing role as a living lab

At Arboretum, researchers find ‘all of the species we would ever want to look at, and then some’

Andrew Groover celebrates the complexity of trees, and makes it his life’s work to unlock how they adapt to their environments. It’s knowledge that’s critical for the U.S. Forest Service research geneticist — he works in California, where concerns about climate change have grown as wildfires there have increased in frequency and intensity.

A practical problem for Groover, who is a University of California, Davis, adjunct professor of plant biology, is efficient access to the variety of trees he studies. His research requires a ready supply of species diversity, a tall order without laborious travel. But in 2012 his search for the perfect resource brought him to the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University — a 281-acre living museum holding more than 2,100 woody plant species from around the world.

“Trees are fascinating for biology and research, but one of the greatest challenges in this research is finding trees tractable for study,” Groover said. “If you have a list of a dozen or two different species, where do you get all those? The Arnold Arboretum has all of the species we would ever want to look at, and then some.”

The Arboretum also contains one of the most extensive collections of Asian trees in the world, which Groover said is advantageous to his research. Typically a researcher has to travel to various locations throughout the world, determine whether the trees are on public or private property, obtain permission to study and transport samples, overcome language and other barriers, and potentially return to the same site later to complete research, which can be challenging.

“The Arnold Arboretum plays a crucial role in research and science and educating the public, connecting them with trees and forests. But it’s also a living laboratory and repository of hard-to-source species for research and is renowned for its collection of Asian disjuncts,” he said. “We can actually study these species pairs found in both Asia and the U.S. directly in the Arboretum. We didn’t need to go anywhere else.”

Director of the Arnold Arboretum and Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology William (Ned) Friedman emphasized the extraordinary efforts that go into creating such a high-impact research destination.

“Importantly, beyond the more than 16,000 accessioned woody plants at the Arnold Arboretum, we have a staff of world-class horticulturists, propagators, IT professionals, curators, and archivists, all of whom are devoted to ensuring that the living collections are what I call a ‘working collection’ of plants,” he said. “The plants of the Arboretum may look great in flower, or at the peak of fall colors, but these plants are here primarily to be studied by scholars at Harvard and from around the world. In 2018 alone, there were 79 different research projects using the living collections and landscape of the Arnold Arboretum.”

Groover’s work with the Arboretum became a long-term collaboration. In 2014 he won a Sargent fellowship, and, working with Arboretum scientists, collected small samples of genetic material from specific Arboretum trees and propagated them in his own laboratory greenhouses. In 2015 Groover, with Friedman, organized the 35th New Phytologist Symposium held at the Arboretum. He has also given several research talks there, most recently in December on genomic approaches to understanding the development and evolution of forest trees.

“When the Weld Hill Research Building was completed [in 2011], many of us in the research community saw that as a real commitment holding great possibilities for expanding into new areas of research,” he said. “We could not only access a broad range of species all in one location, we had a physical facility for research activities.”

Groover’s work investigates genetic regulation of wood formation — the triggers of gene expression within the wood — which is driven by environment, including light, temperature, wind, water, gravity, even insects and disease. Studying diverse tree species helps him identify the genetic basis of how different species modify their growth and adapt to different environmental conditions.

“Trees in general are very responsive to the environment, and trees can actually make adjustments in their wood anatomy to suit the environment,” Groover said. “One thing that is really interesting about trees is that they are perennial and live to decades or even thousands of years in the same place, and they have to be able to cope with all of the variation.”

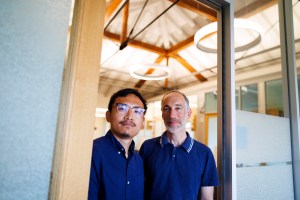

Suzanne Gerttula, a research assistant with Andrew Groover, has an interest in the underlying mechanisms of trees’ responses to gravity, such as occurs in weeping varieties.

Photo by Andrew Groover

The collaboration with the Arboretum is special because its trees contain valuable provenance.

“The trees are well-cared for, are not likely to disappear or die so you can go back again, and they are all right there next to each other,” Groover said.

While his in-depth research is on poplars (Populus spp.), the knowledge obtained may be beneficial in the study of many other tree species.

“If the genetic regulation of a trait is conserved among species, then what we learn in poplar can be transferred to the hundreds of other species we would like to be able to better manage or understand,” Groover said. “We can transfer knowledge across different species and potentially use that information in the future for things like reforestation and restoration.”

Suzanne Gerttula of the Forest Service began working in developmental plant genetics more than three decades ago and joined Groover’s laboratory in 2010. The former staff research associate in plant biology at U.C., Davis, has an interest in the underlying mechanisms of trees’ responses to gravity, such as occurs in weeping varieties.

“The Arboretum is an incredible resource for both weeping and upright trees. It’s fascinating, fun, and inspiring to me to be able to get at the some of the biochemical bases of how life works,” she said.

Groover’s enthusiasm for his subject spans sectors from ecological to economic. From understanding Earth cycles and climate change to helping the lumber, paper, fiber, and even biofuel industries, he hopes his research can inform solutions for forest management and conservation and identify new forms of renewable energy.

“I think it’s important we have places like the Arnold Arboretum to help provide this sort of basic information that has the potential to help in the conservation and management of forests,” he said.

Michael Dosmann, Keeper of the Living Collections at the Arboretum, said it has research potential across a wide swath of disciplines — taxonomic, horticultural, plant conservation, ecology, and developmental biology.

“Our living collection’s research potential could never be exhausted; there is a constant need for its use, growth, and development,” he said. “[The] dynamic interplay between living collections and scientific research demonstrates the vital importance collections have to science and to society.”

Scientists such as Groover enjoy access not only to the living collections, but also to other Arboretum resources, including affiliated collections containing herbarium specimens, archives, images, historical records, on-site greenhouse and laboratory space, centralized expertise, and, frequently, financial assistance in the form of grants and fellowships.

“All too often, the cost both in time and dollars of assembling collections at their own institutions is prohibitive for researchers, making places like the Arboretum a vital resource, especially for those working with limited budgets,” Dosmann said.

Evolving technology also plays a critical role, according to Dosmann, giving researchers the ability to access the Arboretum’s expansive resources, and making plant species more attainable.

“With the aid of databases and other information systems, it is now much easier to see collections in the multiple dimensions within which they exist and appreciate their unlimited research potential,” he said.

Groover said that with forests facing multiple threats, there’s never been a more important time to address forest biology and the use of technology.

“In the west especially, we need new insights into how to make forests more resilient to drought and heat, including understanding the biology underlying stress responses in different tree species,” he said. “We are learning the complexities of forest trees and hope to ultimately be able to select genotypes or species that might perform better in the future. Working with the Arboretum offers the resources for this important research.”