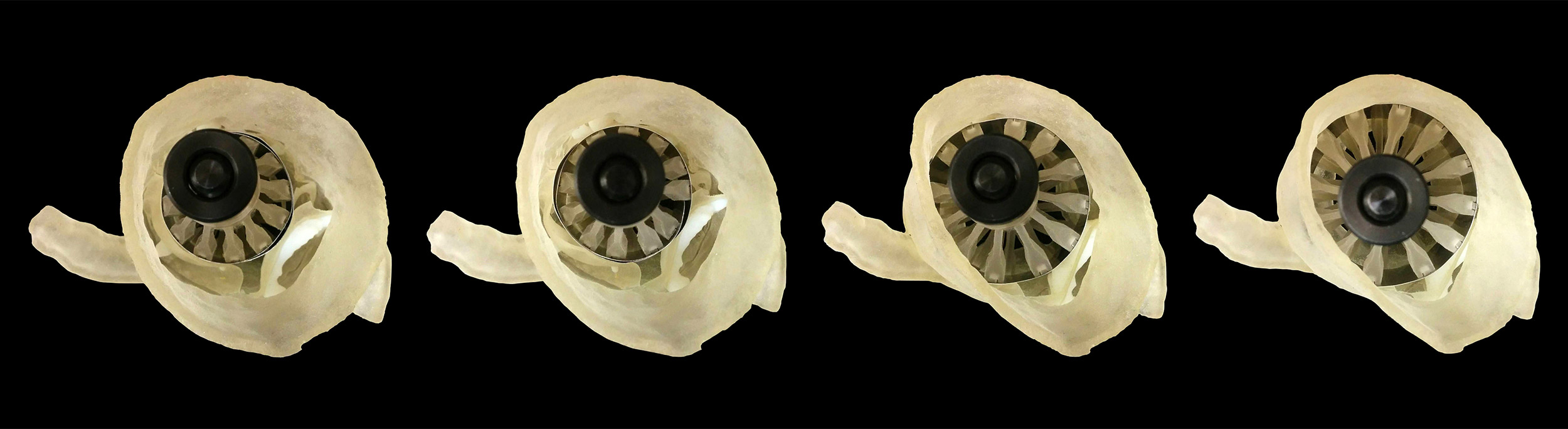

Examples of aortic heart valves, each with its own unique size, shape, and varying amounts of calcification.

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Size a concern when replacing heart valves

3-D printer helps determine accurate fit for fewer leaky valves

More than one in eight people age 75 and older in the U.S. develop moderate to severe blockage of the aortic valve in their hearts, usually caused by calcified deposits that build up on the valve’s leaflets and prevent them from fully opening and closing.

Many of these older patients are not healthy enough to undergo open-heart surgeries; instead, they have artificial valves implanted into their hearts using a procedure called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), which deploys the valve via a catheter inserted into the aorta.

There are challenges with this procedure, however, including the need to choose the perfect-size valve without ever actually looking at the patient’s heart. Too small, and the valve can dislodge or leak around the edges; too large, and the valve can rip through the heart, carrying a risk of death. Like Goldilocks, cardiologists are looking for a TAVR valve size that is “just right.”

Researchers at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have created a novel 3-D printing workflow that allows cardiologists to evaluate how different valve sizes will interact with each patient’s unique anatomy, before the medical procedure is actually performed. This protocol uses CT scan data to produce physical models of individual patients’ aortic valves, in addition to a “sizer” device to determine the perfect replacement valve size. The work was performed in collaboration with researchers and physicians from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the University of Washington, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, and is published in the Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography.

“If you buy a pair of shoes online without trying them on first, there’s a good chance they’re not going to fit properly. Sizing replacement TAVR valves poses a similar problem, in that doctors don’t get the opportunity to evaluate how a specific valve size will fit with a patient’s anatomy before surgery,” said James Weaver, a senior research scientist at the Wyss Institute who is a corresponding author of the paper. “Our integrative 3-D printing and valve-sizing system provides a customized report of every patient’s unique aortic valve shape, removing a lot of the guesswork and helping each patient receive a more accurately sized valve.”

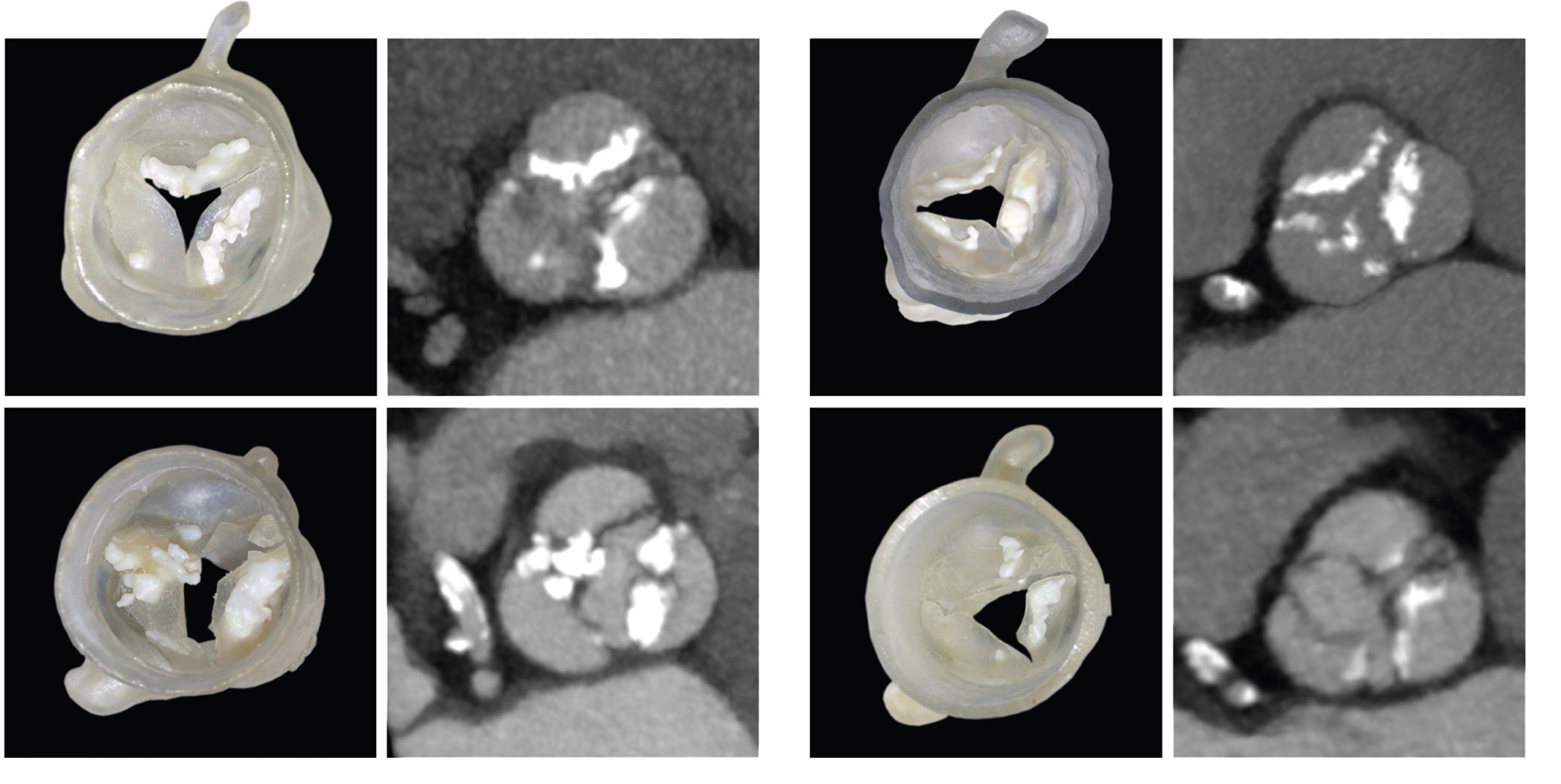

A custom “sizer” device is placed inside each 3-D printed heart valve model and gradually expanded until the proper fit is achieved.

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

When patients needs a replacement heart valve, they frequently get a CT scan, which takes a series of X-ray images of the heart to create a 3-D reconstruction of its internal anatomy. While the outer wall of the aorta and any associated calcified deposits are easily seen on a CT scan, the delicate “leaflets” of tissue that open and close the valve are often too thin to show up well. “After a 3-D reconstruction of the heart anatomy is performed, it often looks like the calcified deposits are simply floating around inside the valve, providing little or no insight as to how a deployed TAVR valve would interact with them,” Weaver explained.

To solve that problem, Ahmed Hosny, who was a research fellow at the Wyss Institute at the time, created a software program that used parametric modeling to generate virtual 3-D models of the leaflets using seven coordinates on each patient’s valve that were visible on CT scans. The digital leaflet models were then merged with the CT data and adjusted so that they fit into the valve correctly. The resulting model, which incorporated the leaflets and their associated calcified deposits, was then 3-D printed into a physical multimaterial model.

The team also 3-D printed a custom “sizer” device that fit inside the valve model and expanded and contracted to determine what size artificial valve would best fit each patient. They then wrapped the sizer with a thin layer of pressure-sensing film to map the pressure between the sizer and the 3-D-printed valves and their associated calcified deposits, while gradually expanding the sizer.

“We discovered that the size and the location of the calcified deposits on the leaflets have a big impact on how well an artificial valve will fit into a calcified one,” said Hosny, who is currently at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “Sometimes, there was just no way a TAVR valve would fully seal a calcified valve, and those patients could actually be better off getting open-heart surgery to obtain a better-fitting result.”

In addition, the multimaterial design of the 3-D-printed valve models, which incorporate flexible leaflets and rigid calcified deposits into a fully integrated shape, could much more accurately mimic the behavior of real heart valves during artificial valve deployment, as well as provide haptic feedback as the sizer expanded.

The team tested their system against data from 30 patients who had already undergone TAVR procedures, 15 of whom had developed leaks from valves that were too small. The researchers predicted, based on how well the sizer fit into the 3-D-printed models of their aortic valves, what size valve each patient should have received, and whether they would experience leaks after the procedure. The system was able to successfully predict leak outcome in 60 percent to 73 percent of the patients (depending on the type of valve each had received), and determined that 60 percent of the patients had received the appropriate size of valve.

“Being able to identify intermediate- and low-risk patients whose heart-valve anatomy gives them a higher probability of complications from TAVR is critical, and we’ve never had a noninvasive way to accurately determine that before,” said co-author Beth Ripley, an assistant professor at the University of Washington who was a cardiovascular imaging fellow at Brigham and Women’s when the study was done. “Those patients might be better served by surgery, as the risks of an imperfect TAVR result might outweigh its benefits.” Additionally, being able to physically simulate the procedure might inform future iterations of valve designs and deployment approaches.

The team has made the leaflet modeling software and 3-D-printing protocol freely available online. They hope their project will serve as a springboard for evolvable biomedical design that keeps pace with the market’s state of the art.

“At the core of the personalized medicine challenge is the realization that one medical treatment will not serve all patients equally well, and that therapies should be tailored to the individual,” said Wyss Institute Founding Director Donald Ingber, who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as professor of bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “This principle applies to medical devices as well as drugs, and it is exciting to see how our community is innovating in this space and attempting to translate new personalized approaches from the lab and into the clinic.”

Additional authors of the paper include Joshua Dilley from Massachusetts General Hospital; Tatiana Kelil, an assistant professor at University of California, San Francisco, and former resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Moses Mathur of the University of Washington Medical Center; and Mason Dean of the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Germany.

This research was supported by the Human Frontier Science Program.