An artist of the avant-garde and the everyday

Courtesy of Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University

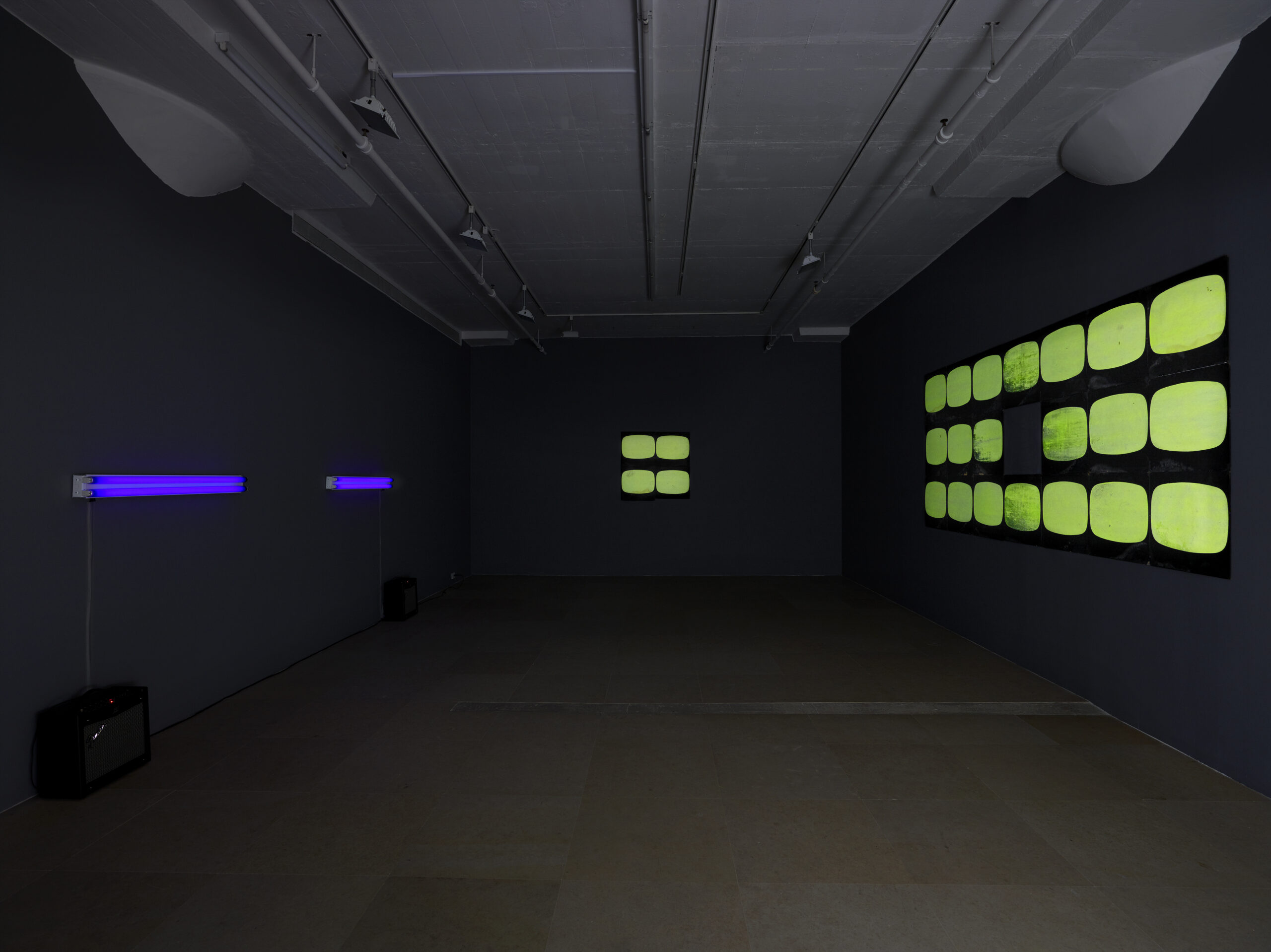

Two-campus exhibit showcases the mirthful creations of Tony Conrad

As someone who embraced both “the kitchen table and the avant-garde,” in the words of curator Dan Byers, Tony Conrad ’62 was never a gallery darling. Instead, the multimedia artist believed in making the creative process as accessible as possible — and ended up pushing the boundaries of film, sculpture, video, and music along the way.

The artist’s work is being celebrated in “Introducing Tony Conrad: A Retrospective” at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (through Dec. 30) and MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (through Jan. 6).

The description by Byers, the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director of Carpenter Center, can be taken literally. The exhibit, which was organized by Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery, reveals all the humor that juxtaposition implies.

On the lower level of the Carpenter exhibit (organized by Byers and List curator Henriette Huldisch), Conrad’s work “Pickled E.K. 7302-244-0502” is just that: celluloid loops fixed forever in Mason jars, a play on “film preservation” and a commentary on home arts and crafts. The third-floor display features impossible musical instruments — Conrad played violin — incorporating, among other items, a drill and a bathroom plunger.

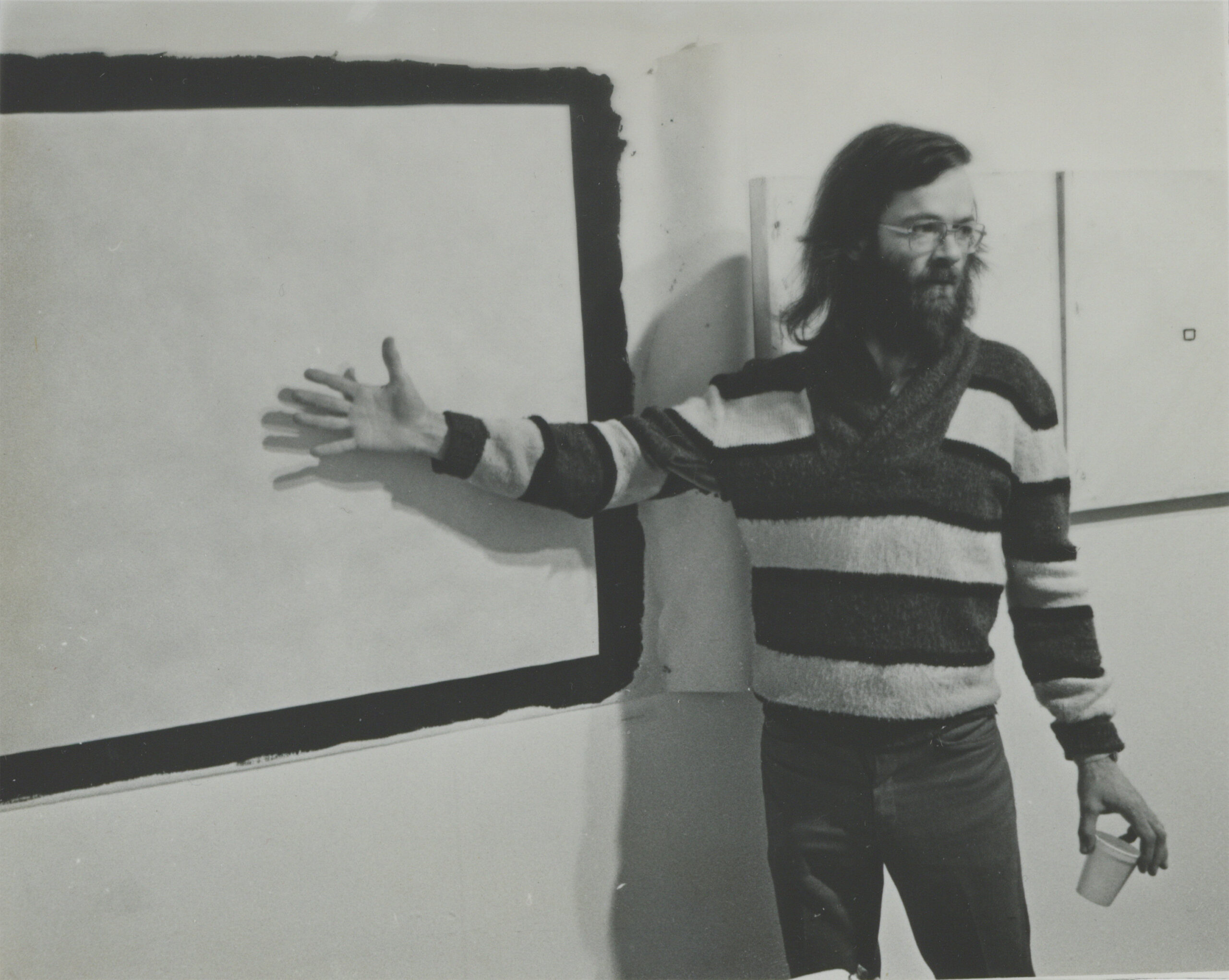

In some ways, Conrad, who died in 2016 at age 76, was an artist very much of his time. Coming of age as a filmmaker and musician in the 1960s, he was an original member of the drone-centered Theatre of Eternal Music, along with John Cale, and embodied both the experimental and minimalist movements of the day. His “Yellow Movies” series, for example, features paper painted with white paint, which would gradually yellow over time. “If you watch it for years, the plot or the narrative would be the yellowing of the paper,” explained Byers.

Tony Conrad in front of “Yellow Movie” in 1973.

© The Estate of Tony Conrad; photo by Kevin Noble

Although he did eventually show in galleries, using the funds raised to finish and restore some of his earlier works, he remained “very suspicious about the commodification of art.”

For “Studio of the Streets,” Conrad recorded the conversations of passers-by and aired edited excerpts on public access cable television.

Courtesy of Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University

What this exhibit quickly makes apparent, however, is the social consciousness beyond the humor, the politics behind the pranks. From an early photo, which shows him protesting what his sign derides as “Snob Art,” through such works as “Loose Connection,” filmed using a rotating camera set in a repurposed baby carriage during a family grocery-shopping trip in New York, Conrad believed in art by, for, and of the people.

Although he did eventually show in galleries, using the funds raised to finish and restore some of his earlier works (which explains the dual dates on many pieces), he remained “very suspicious about the commodification of art,” said Byers. Even “Bryant Park Moratorium Rally,” a seemingly straightforward sound piece, makes this point. Contrasting the crowd noise taped outside Conrad’s window during a 1969 anti-war rally with the delayed, somewhat subdued version that was broadcast over the television news a few seconds later, we hear “an event and its mediation put up against each other,” said Byers. “Two different windows on reality.”

This ethos is most readily apparent in “Studio of the Streets.” Represented at the Carpenter Center by a one-room installation, this project was an ongoing artists’ collaboration created during Conrad’s time teaching at the University of Buffalo. From 1990–93, Conrad and his colleagues would spend roughly 70 minutes every Friday at Buffalo City Hall, taping conversations with people passing by. The group would edit the results over the weekend and air a 60-minute version on public access cable television the following Tuesday. Their manifesto, presented on one wall, reads in part: “Everyone has good things to say, hear how easy it is … Anyone can make good TV, look at how we do it.”

The conversations are striking. The discussions of Anita Hill’s testimony at Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings could have occurred at last month’s confirmation hearings, for example. Bitterness over perceived police violence is timeless.

“He was very invested in media education for the general public,” remembered Lindsey Lodhie.

A Ph.D. candidate in film and visual studies and critical media practice in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Lodhie studied with Conrad while earning her master’s at Buffalo. “He saw it as a public service, in a way.”

“He showed up to everything, and he instigated all these things,” said Byers. “He showed up.”

From 7 to 9 p.m. Fridays (Nov. 16 and 30) at the Carpenter Center, a two-part program of Tony Conrad’s pioneering video work will be presented in collaboration with Harvard Film Archive. For more information about this and upcoming programs, visit the website.