Thomas Glynn (left) and Nitin Nohria discuss plans for Harvard’s Enterprise Research Campus in Allston.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard forms subsidiary to advance Enterprise Research Campus

HBS dean, former Massport chief share leadership vision for 36-acre Allston project

Harvard has announced the next step in its efforts to create a 36-acre Enterprise Research Campus in Allston: the formation of a wholly owned subsidiary to oversee development, with Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria serving as chair of the governing board and former Massport CEO Thomas Glynn as chief executive officer.

The campus, across Western Avenue from Harvard Business School and next to the almost-completed Science and Engineering Complex, will include a collection of research-focused companies of all sizes, along with green space, residences, and a hotel and conference center. Initial plans cover the first, 14-acre phase of development.

President Larry Bacow said that the Enterprise Research Campus will foster Harvard’s broader mission by providing a place where students can discover cutting-edge research and by attracting companies that can develop research into products that reach the public.

“Universities exist to do a number of things,” he said. “We educate students, we generate new knowledge, and, through both activities, we seek to create a better world. I think the Enterprise Research Campus gives us an opportunity to accomplish all three of those objectives at a higher level.”

Bacow expects the campus to enliven existing activities in Allston and to amplify the work of Harvard researchers.

“I think it’s going to bring enormous energy to Allston and to the academic campus in Allston,” he said. “It will bring different people. It will bring different activities. It will help to bring housing, retail, and other functions.

“Over time, it will prove to be an amplifier for the research that we do in Allston, because it’s our intent to try to recruit idea-intensive businesses to the Enterprise Research Campus that have a natural synergy with the scholarship that’s going on by our faculty and students in Allston.”

The Enterprise Research Campus in Allston will include research-focused companies, green space, residences, and a hotel and conference center.

Courtesy of Harvard Planning Office

Nohria and Glynn are a good pair to lead the project, he added. Nohria, who will chair the governing board, knows both Harvard and the business world, while Glynn has experience across a diverse range of enterprises — hospitals, universities, government — important in Greater Boston and to the new campus’ success.

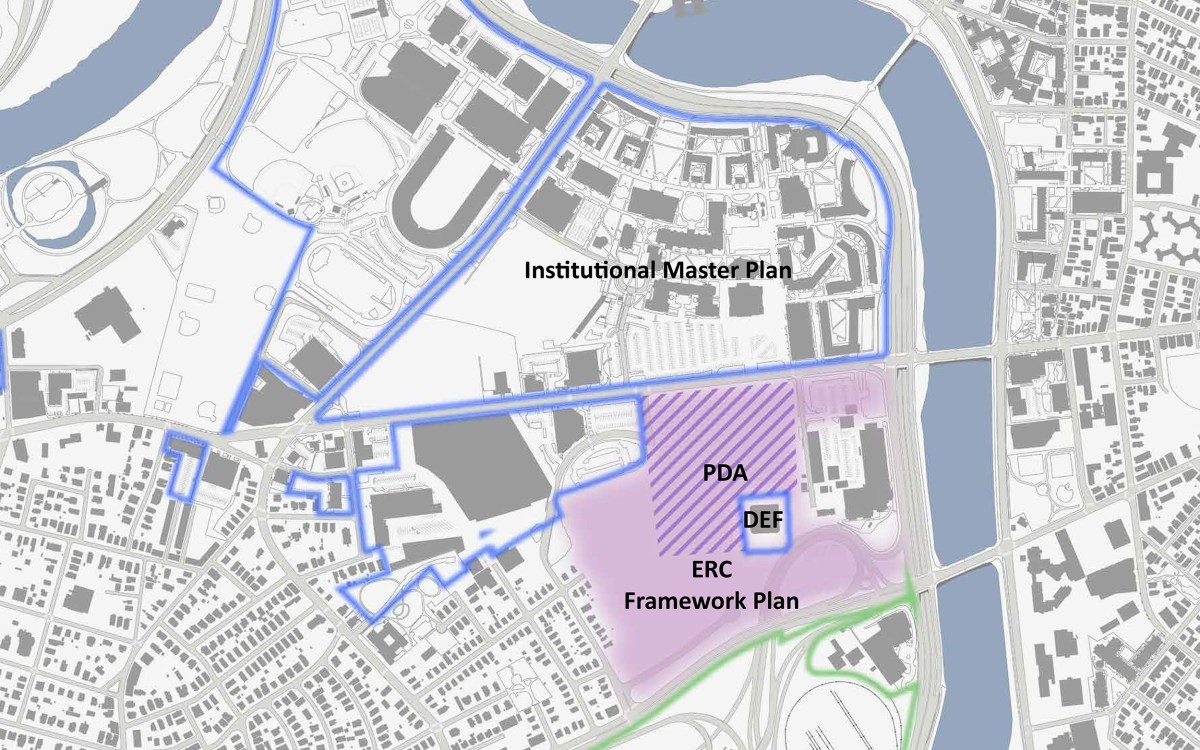

In March, the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) approved a planned development area (PDA) master plan for the initial 14 acres of the Enterprise Research Campus, to include infrastructure, streets, and open space supporting an approximately 900,000-square-foot, mixed-use development of office and lab space, residential units, and a hotel and conference center.

In an interview with the Gazette, Nohria and Glynn touched on how the campus will interface with the neighborhood and existing Harvard activities, its alignment with the region’s long history of innovation, and how it sets the table for future development.

Q&A

Nitin Nohria and Thomas Glynn

GAZETTE: How would you describe the region’s desire for a project like the Enterprise Research Campus?

NOHRIA: The Greater Boston region has always been a hub of innovation. Starting with the American Revolution, one could say the entire country was invented here. We’ve had an amazing history. Now, as we look at life sciences and what’s happening with continuing advances in information technology, we’re once again at the nexus of an extraordinary period of innovation.

We have Kendall Square, and it’s just amazing to see how quickly the Boston Waterfront has become another innovation hub. We’ve always had Longwood. Allston joining the mix becomes part of the enormous set of possibilities this region has to offer.

GLYNN: I agree. I think that some of the other areas of the city that have been focused on innovation are becoming more mature, and this is an opportunity to start a new innovation area and a new neighborhood. So it’s an unprecedented opportunity.

GAZETTE: What’s the rationale? Why use the land this way and not for more dorms, classrooms, and museums?

NOHRIA: Harvard has close to 190 acres in Allston dedicated to institutional uses — there’s plenty of land available for Harvard to pursue its most important institutional projects and collaboration across the University.

The companies we hope to attract to the ERC might be places where our students find exciting internships and jobs. They may inspire students to create new companies. They may be research enterprises with which our scholars will forge productive collaborations.

But we want to [create] a place that is not an island unto itself. We want to be connected to other institutions — to arts institutions and culture, to neighborhoods in which people live and work. And we have the ability to create this in this enterprise zone.

If you create a lively ecosystem of which the University is a part, it makes everyone better — it makes the people who are here feel they benefit from being part of the University and makes the University benefit from having these interactions with people who are beyond the University and yet connected to it.

GAZETTE: If the development is a success, what will it look like in five or 10 years?

NOHRIA: This is a project that will operate on multiple timescales. It’s worth noting that it’s taken Harvard almost 400 years to develop 214 acres in Cambridge. So we should not be impatient.

But in the short run, we think that Western Avenue, and the land adjoining Western Avenue, is probably the first place where, in the five-to-10-year horizon, we should start to see significant action. We already have the engineering school on one side of Western Avenue, and there are commercial and retail projects like the Continuum [apartments] around Barry’s Corner.

There’ll be other things occurring, maybe in the background, but not less important. We want to take advantage of the immediate opportunities, but also use these five to 10 years to create opportunities for the future.

GLYNN: I think that a lot has been done in the last 10 years, as the dean just indicated. The Continuum project, the SEAS building, innovation — the three innovation labs — and some of the new retail. …

NOHRIA: The arts lab will also open soon.

GLYNN: That’s right.

NOHRIA: And then there’s the Harvard Ed Portal, bringing various education and enrichment programs directly to the Allston community, as well as the Office for the Arts Ceramics Program next door. It feels like these are projects where the parts and the whole have not yet come together. In the next five to 10 years you’ll begin to see what feel like singular projects get united into a more coherent whole.

GAZETTE: What will be the daily life of the campus? Are residents walking their dogs or do you see people driving to work and going into labs and coming back out and driving home?

GLYNN: The hope is that it’s all of the above. People will be coming to work there, but also people will be at play in the neighborhood. They’ll be walking their dogs; people from the Allston residential neighborhood will be taking a walk on the green space. So it should be open to all — employees, students, and people from the neighborhood. I think that would be the hope.

NOHRIA: I think that if this does not feel like an integrated neighborhood we will have failed. By integrated, I mean integrated in terms of life and work, integrated in terms of current Allston residents and the new people who will come. Integrated in terms of Harvard and other members of the community.

GAZETTE: Will the Enterprise Research Campus advance Harvard’s teaching and research mission, or is it seen as apart from that?

NOHRIA: I think it has to be integral to that. Our goal is to invite into the Enterprise Research Campus companies that have a research and intellectual intensity. It’s not called the commercial zone, it’s called the Enterprise Research Campus, and I think the word “research” should not be taken lightly. It will become quite intimately tied to the research and teaching enterprise of Harvard University.

GAZETTE: Will students be doing internships there? Will there be faculty research?

More like this

NOHRIA: I hope they’ll be doing internships and getting full-time jobs when they graduate. We hope that faculty members will join research projects. There’s already a fair amount of sponsored research across the University. We imagine more of that will occur.

We have one of the most fertile startup ecosystems now at Harvard. Many of these companies, when they grow up, we hope might find a home on the Enterprise Research Campus. They would have natural connections to our faculty, students, and alumni.

GLYNN: I think the investment the University has made in the SEAS building will provide intellectual seed capital to attract companies that are compatible in the way the dean is describing. So I think we will be picking among organizations that all want to be part of this next chapter.

GAZETTE: And do you see a particular size company?

NOHRIA: It’s really important to have a portfolio — to get a good distribution of startups to midsized companies to large companies with research labs here.

GAZETTE: Has this model been used in the past? What other areas could you point to as examples?

GLYNN: I think there’s a lot to learn from the success MIT has had in Kendall Square. I know Brookings did a study four or five years ago that looked at other examples across the country. But Allston is a unique situation where you have available land adjacent to a great university. Most other places have to knock something down to put something up or are more distant from a university.

GAZETTE: Will this strengthen connections with other institutions?

NOHRIA: Absolutely. Once the turnpike project is completed, we will abut Boston University. In some 20- to 30-year future, we will walk across a bridge and take the Green Line. Imagine a University that is connected to the Red Line on the one hand and the Green Line on the other. In a world of autonomous driving, we could get connected even more quickly than through big infrastructure projects. I don’t know what the world looks like 20, 30 years from now, but there’s no other place with the same potential as Allston.

Just think of some of the big centers of innovation on the West Coast that are miles apart. Here, we’re talking about four major innovation districts that are within a few miles of each other: Longwood, the waterfront, Kendall Square, and Allston. The Tufts and Porter Square neighborhood isn’t much farther away. It’s a pretty rare thing to have this much density in one location.

GAZETTE: What are the first steps to getting going?

GLYNN: Nitin and I are having conversations about the [subsidiary’s] structure, the staffing, the budget, how the board is going to interact with staff. While we’re doing that, we can’t afford to let the [planning] work not progress. A lot of great work has been done. We’re not starting from scratch.

NOHRIA: The goal is to create a lean and effective organization. Then there are developers to be found. There’s an RFP that has to be developed. We already have about a million square feet approved by the city. We want to get moving on that work [of creating the research campus infrastructure and buildings]. And then it’s about inviting companies [to work there]. How do we select them? How do we make this compelling so we get the broadest reach?

Then, since there will be residential development as well, what should the street life look like? What does after-hours look like? We would like it to be lively. How do we make sure that that happens? So, that’s the execution side of this.

And then, there’s always long-run planning that we need to continue to do. These 14 acres are Act I. And there isn’t an Act II unless you start planning for Act II even as you’re doing Act I.

GAZETTE: Tom, what attracted you to this opportunity?

GLYNN: Well, there was the opportunity to work with Larry Bacow, who I’ve known for a while; to work with Nitin; to work with [Executive Vice President] Katie Lapp. I’ve been following [Harvard’s Allston development] as a citizen of Boston for a while. I was, for a couple of terms, on the Harvard Corporation’s Committee on Facilities and Capital Planning, so I followed it then. It is a great opportunity to work with great people, and was an easy decision.

NOHRIA: We were attracted to Tom because he’s someone who’s done amazing projects in this city. It’s rare to find someone who’s worked in every institutional setting — with the major hospitals, the major universities, with the state itself. Tom brings a unique set of capabilities and has seen this from all different angles.