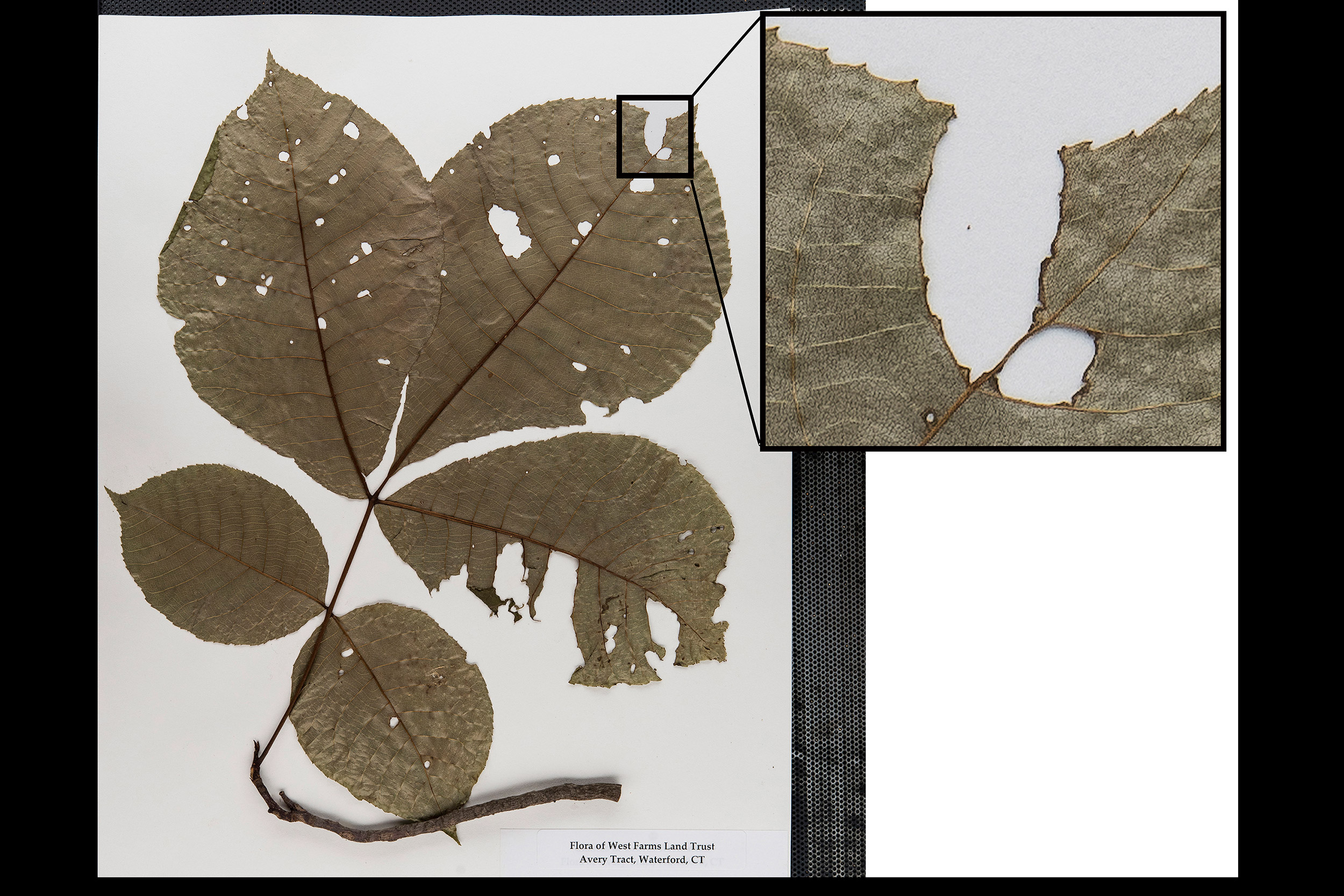

A study has found that plant specimens collected in the early 2000s were 23 percent more likely to be damaged by insect herbivores than those that were collected in the early 1900s.

Courtesy of Emily Meineke

Understanding insect damage over time

Study uses herbarium samples to map links between climate changes and bugs’ eating patterns

When she set out to understand whether climate changes over the past century were affecting insects’ patterns of eating and damaging various plants, Emily Meineke decided to go straight to the source: the vegetation samples.

A postdoctoral researcher working in the lab of Charles Davis, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and director of the Harvard Herbaria, Meineke is the lead author of a first-of-its-kind study that used herbarium specimens to track insect herbivory (the eating of plants) across more than 100 years. The study is described in a Sept. 4 paper published in the Journal of Ecology.

The paper is co-authored by Aimée Classen and Nathan Sanders, who are affiliated with the University of Vermont and the Gund Institute for Environment, and Jonathan Davies, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia.

Across four species — shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), showy tick trefoil (Desmodium canadense), and wild lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) — the study found that specimens collected in the early 2000s were 23 percent more likely to be damaged by insect herbivores than those collected in the early 1900s.

The data also showed that insect damage was greater following warmer winters and at low latitudes, Meineke said, suggesting that higher temperatures driven by climate change could be a factor driving insect damage.

“The overwhelming pattern is that across these four different plant species, with different life histories, insect damage is increasing over time,” she said. “In New England, it appears that warming in winter is an important factor driving insect herbivory damage overall.

“Knowing that insect damage on these plants is increasing is useful because we might be able to come up with management strategies before it reaches economic levels,” she continued. “I think this study is the tip of the iceberg. Now that we know these plants have more damage than they did 100 years ago, we can try to understand what that actually means for plants.”

To understand whether herbivory was increasing, Meineke and colleagues developed a detailed system for measuring not just whether specimens showed insect damage, but how much.

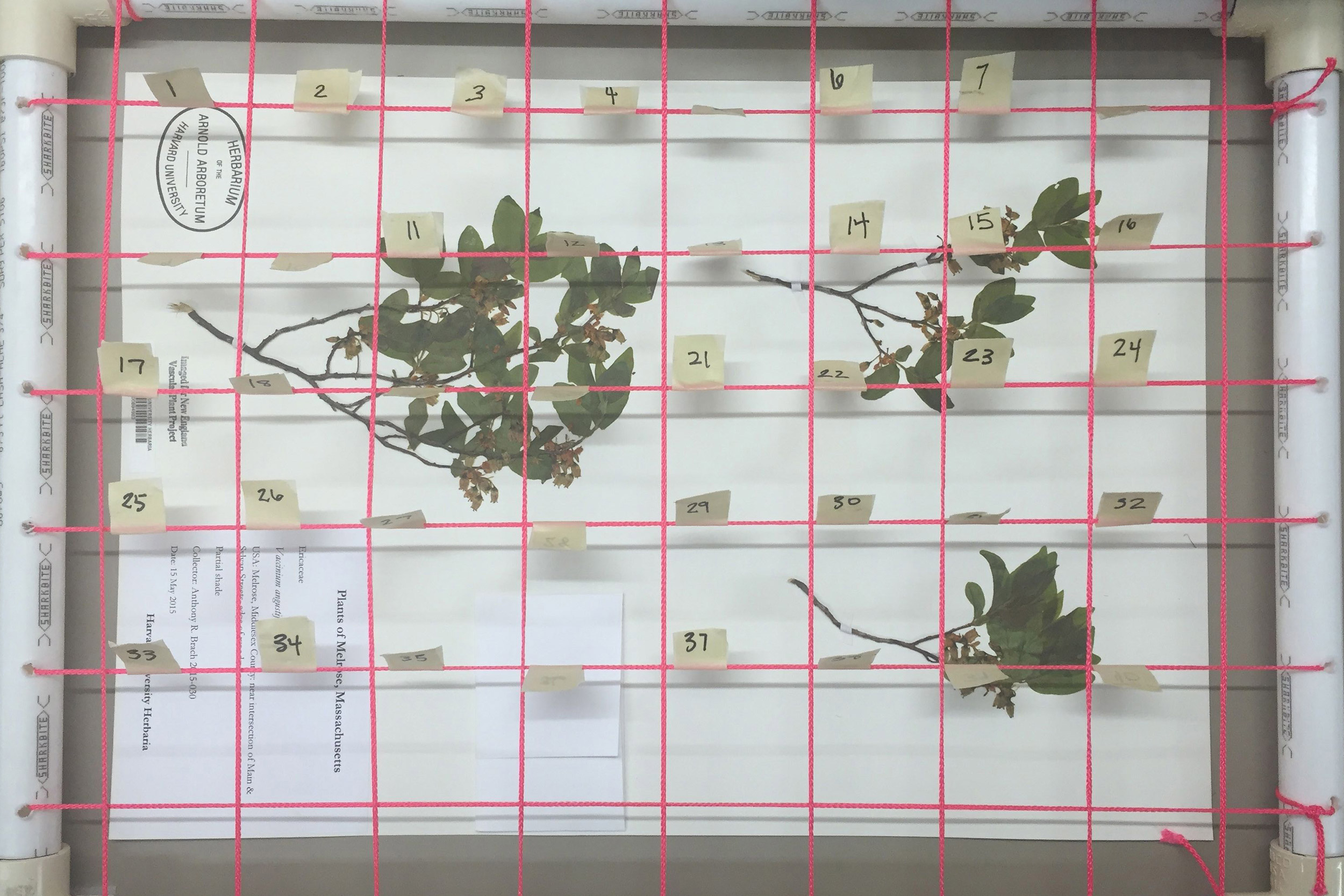

“It’s hard to quantify the value of these collections,” said Emily Meineke, “because in fact they’re invaluable. You can’t go back and collect them again …”

Courtesy of Emily Meineke

“Instead of just outlining the amount of a specimen that we think was removed by insects, or just saying this specimen has damage or doesn’t, we actually wanted to be able to quantify it,” Meineke said. “To do that, we laid a grid over each specimen, then randomly selected five grid cells and marked whether the leaves inside the grid cell were eaten or not, so our approach was a fine-scale measurement.”

One of the challenges the study faced, Meineke said, came in understanding exactly what damage in the specimens was caused by insects.

“Vertebrates chomp off either half a leaf or the whole leaf,” she said. “That’s rare on herbarium specimens. When insects eat the plants before they’re collected, the plant leaves a sort of scar around the damage that’s analogous to a human scar.

“But the trouble is that the plants are also eaten within herbaria by a suite of herbivores, and particularly for the older specimens that weren’t as well protected, we had to figure out a way to tell when specimens had been eaten before they were collected, and this type of scar tissue is found on just about every plant species we looked at.”

Armed with that data, Meineke and colleagues developed a model to examine how herbivory changed over time, but ran into another hurdle in the fact that herbarium specimens aren’t randomly sampled.

“What you would hope for is to have a random sample across space collected every few years,” she said. “But instead we have these sporadic samples. One way we deal with that is to include as many variables in the model as we can, so we included the day of year when a specimen was collected, latitude, longitude, and human population density. The idea is that because you have accounted for all of these other variables … that gives you more explanatory power when it comes to what’s happening over time.”

In addition to highlighting the connection between a warming climate and insect herbivory, the study revealed that urbanization can have the opposite effect.

“In New England, it appears that warming in winter is an important factor driving insect herbivory damage overall.”

Emily Meineke

“We know that urbanization has important effects on insects,” Meineke said. “There was a study that looked at 16 cities in Europe and found that the prevalence of insect damage is lower inside cities than outside. We found a similar pattern in New England, and even though it did not explain a lot about how much plants were eaten … urbanization is having a localized effect on insect damage. Overall, though, in New England climate change is having a bigger effect.

“What this means for the future, in my opinion, is that as urbanization accelerates locally, it could counteract the effects of climate change in the sense that you might actually see less insect damage in and around urban centers,” she continued. “But in more rural forests, you’ll see insect damage increasing over time.”

While the study serves to illustrate one of the less-understood aspects of climate change, Meineke said it also highlights the value of herbarium collections in answering such questions.

“It’s hard to quantify the value of these collections,” she said, “because in fact they’re invaluable. You can’t go back and collect them again, and now these specimens have a renewed value because they can help us understand issues like climate change, invasive species, land-use change, and pollution.

“There are debates taking place right now about whether to get rid of physical museum specimens now that many of them are digitized,” she added. “But we can’t because we don’t know what sort of DNA technology or RNA technology might be available in the future to take advantage of these specimens. Even though they’re imperfect and non-randomly sampled, they’re the only records we have.”

This research was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in biology.