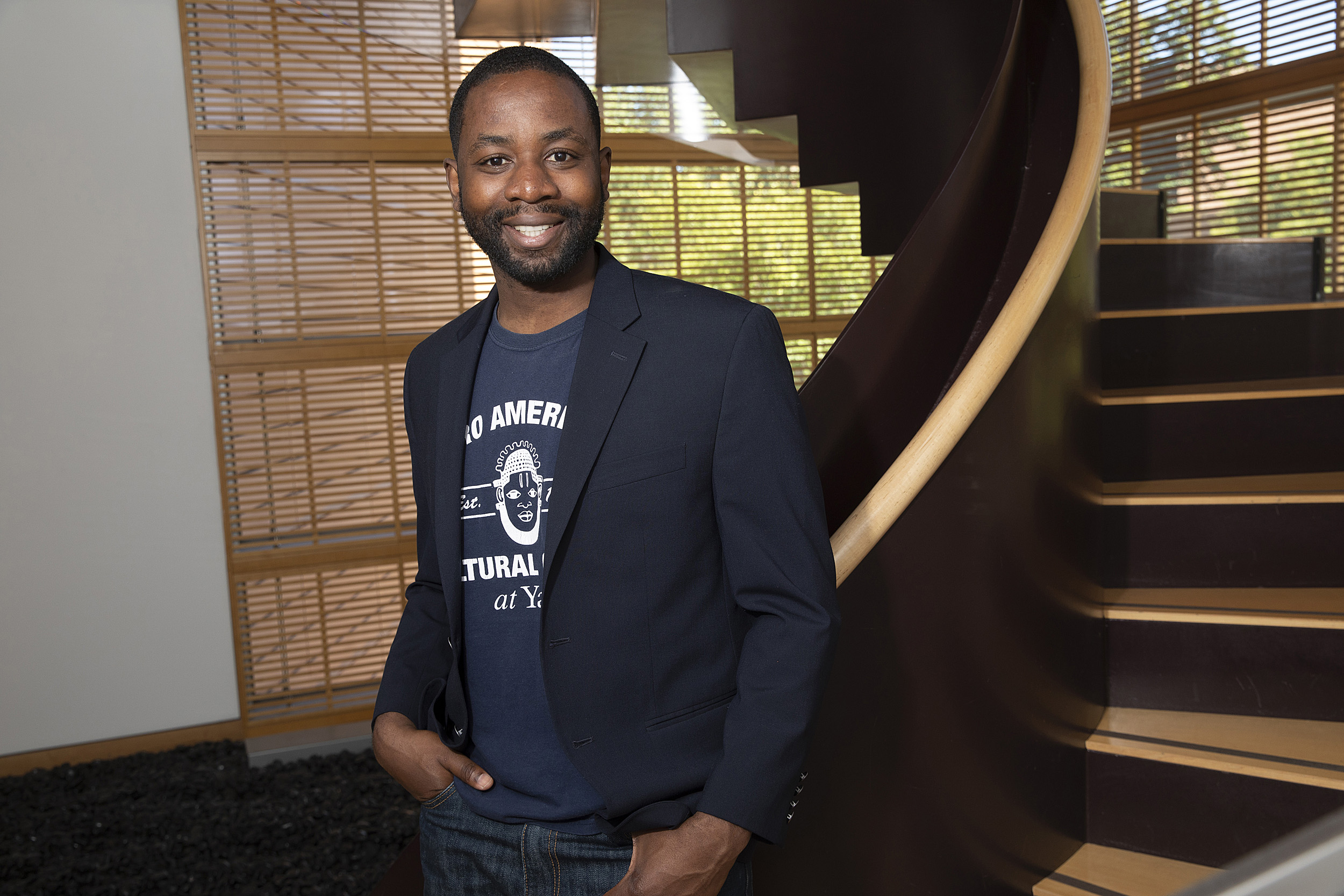

“School was a site of trauma for me,” says Weatherhead fellow Wendell Adjetey, who was born in poverty in Ghana and now holds a Ph.D. from Yale.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Poverty and past failures provide lessons in giving back

Weatherhead fellow works to prep poor for higher education

Wendell Adjetey is paying it forward. One of two incoming William Lyon Mackenzie King Postdoctoral Fellows at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs and its Canada Program, Adjetey, a historian, overcame extreme poverty and its many attendant social ills in his journey from Ghana to Yale and now to Harvard.

This fall, as he begins his program in 20th-century history, writing and teaching a course on African North Americans and citizenship from the Revolutionary War to the present, the foundation Adjetey co-founded will see a member of its first cohort join Harvard’s undergraduate Class of 2022.

Education wasn’t always a given for Adjetey, whose own parents lacked a formal high school education. “School was a site of trauma for me,” he recalls. Not only was his family poor, but his father, then a laborer, was forced to flee Ghana shortly after his youngest son’s birth, his life threatened for criticizing the West African country’s ruling regime.

Thanks to a chance encounter with a Canadian diplomat, his father resettled in Canada. His mother was able to follow a few years later, and Adjetey was raised by his maternal grandmother until his parents could bring him and his two older siblings over in 1992.

Between the family disruption and their poverty, says Adjetey, “all the other challenges were compounded.” As a result, he says, “I consistently performed worse than every other child,” a behavior that was reinforced by his teachers. “I was usually written off in the first couple of weeks of class,” he remembers.

A helping hand — the kind he now wants to extend — changed that. When he was 10 years old, his fifth-grade teacher, Beverly Perez, told him, “I’m not going to let you waste your talents,” he recalls. For Adjetey, this teacher’s confidence in him recalled the love and dignity of his absent parents. “She conveyed a sense of possibility,” he says. He began to believe in himself and to learn.

Once he was in Canada, however, he would hit another roadblock in high school. In part, he was dealing with a lack of resources. In addition, he says now, he was grappling with “what it meant to be a young black man.” When some of his friends became involved in a gang war, school stopped seeming important, and his grades plummeted.

“I failed my senior year,” he says. “That was a slap in the face.” Then a retired guidance counselor called back to replace a counselor on parenting leave took the time to understand what Adjetey was going through and help him plot a path forward.

With the help of that counselor, Peter Hinchcliffe, he repeated his senior year, proceeding to earn undergraduate and graduate degrees at the University of Toronto and a doctorate at Yale. “We had on the surface nothing in common, but he was so compassionate,” recalled Adjetey of the man he describes as “white Anglo-Canadian.”

“I wanted to work so hard to honor him and say thank you.”

In 2015, while still at Yale, Adjetey put his gratitude to work, co-founding the nonprofit Tujenge Africa Foundation with a Rwandan-born classmate, Etienne Mashuli. The foundation (the name means “construct” or “build” in Swahili) aims to boost the potential of the poorest and most marginalized peoples of the African Great Lakes region. While the plan is to expand as resources allow, the first project was an intensive, 18-month gap-year program to prepare students for higher education. In essence, the foundation created a small prep school in a converted house in Burundi, one of the most impoverished countries in the world.

In addition to its educational offerings, Tujenge also focuses on what Adjetey calls “peace building. “ To that end, the Tujenge Scholars, as they are called, are coeducational and bring together students from different ethnic groups, including the Batwa (previously pejoratively identified as “pygmies”). For students whose families have recently been on either side of brutal ethnic cleansing, this leads to some difficult — but necessary — conversations.

“When we discuss ethnic cleansing and ethno-genocide it makes our students cringe,” says Adjetey. “It is that level of discomfort that we need conscientious citizens to engage in” in order to understand and proceed to reconciliation.

“As a historian,” he says, “I know those really critical conversations cannot take place if it’s just one elite group speaking to one another.”

Despite civil upheaval, Adjetey and his co-founder arrived in Burundi during a military coup and the school was up and running by late 2016. In December 2017, it graduated its first cohort of 20 students, one of whom, Eliel Dushime, will come to Cambridge as a member of the Class of 2022 this fall. (A second class of 22 Tujenge Scholars began the program in early 2018.)

“Eliel is a quick study,” said Adjetey. “Not only is he brilliant, but he’s also very thoughtful. When we first met, he asked me how I was able to pursue a doctorate at Yale when my parents are janitors who didn’t have the privilege of a formal education.

“In other words, Eliel wanted me to know that he drew strength from my personal journey, and my belief that our scholars, too, can achieve great feats, notwithstanding their own impoverished and marginal backgrounds.”