‘Aliens’ of the deep captured

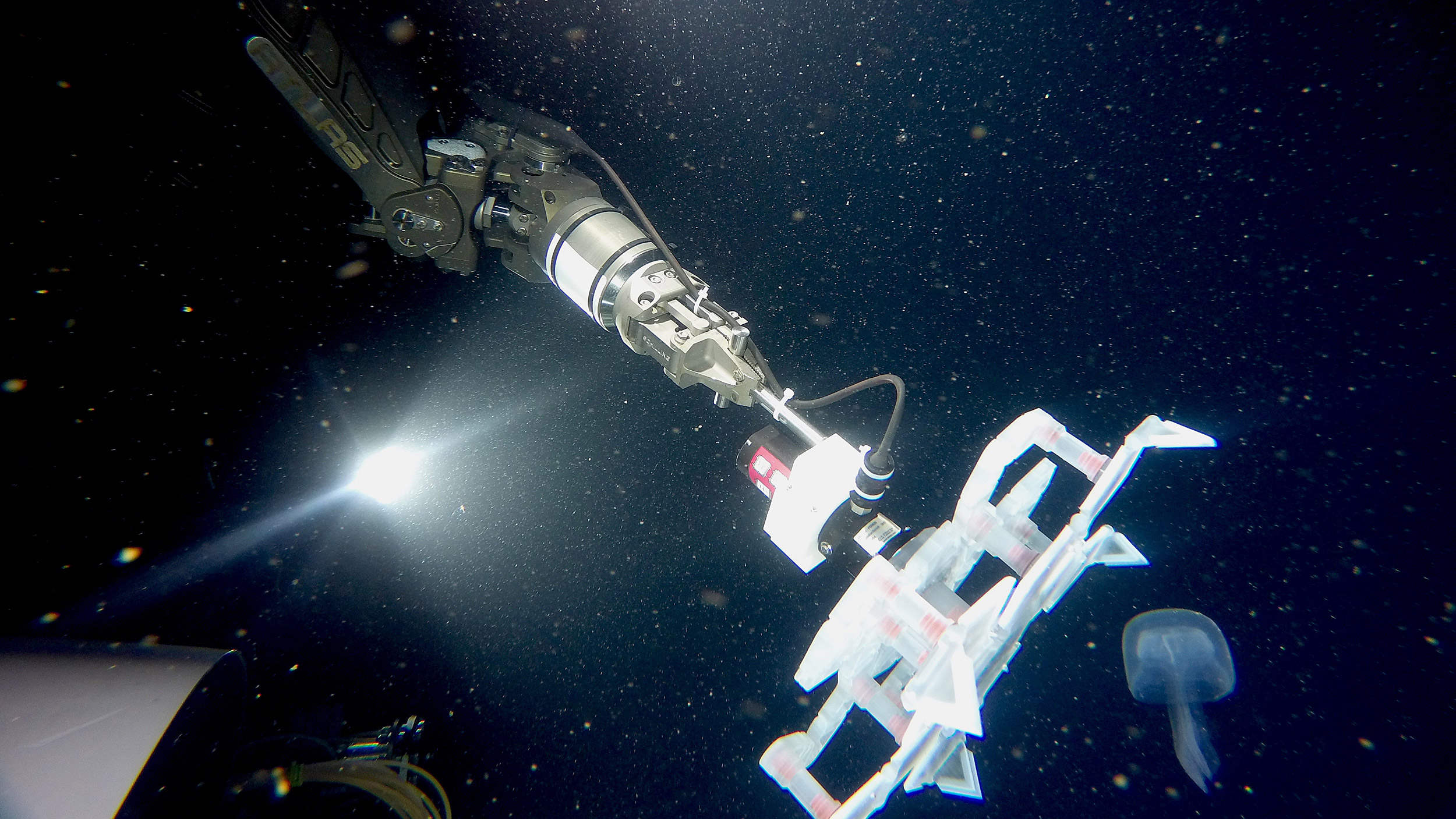

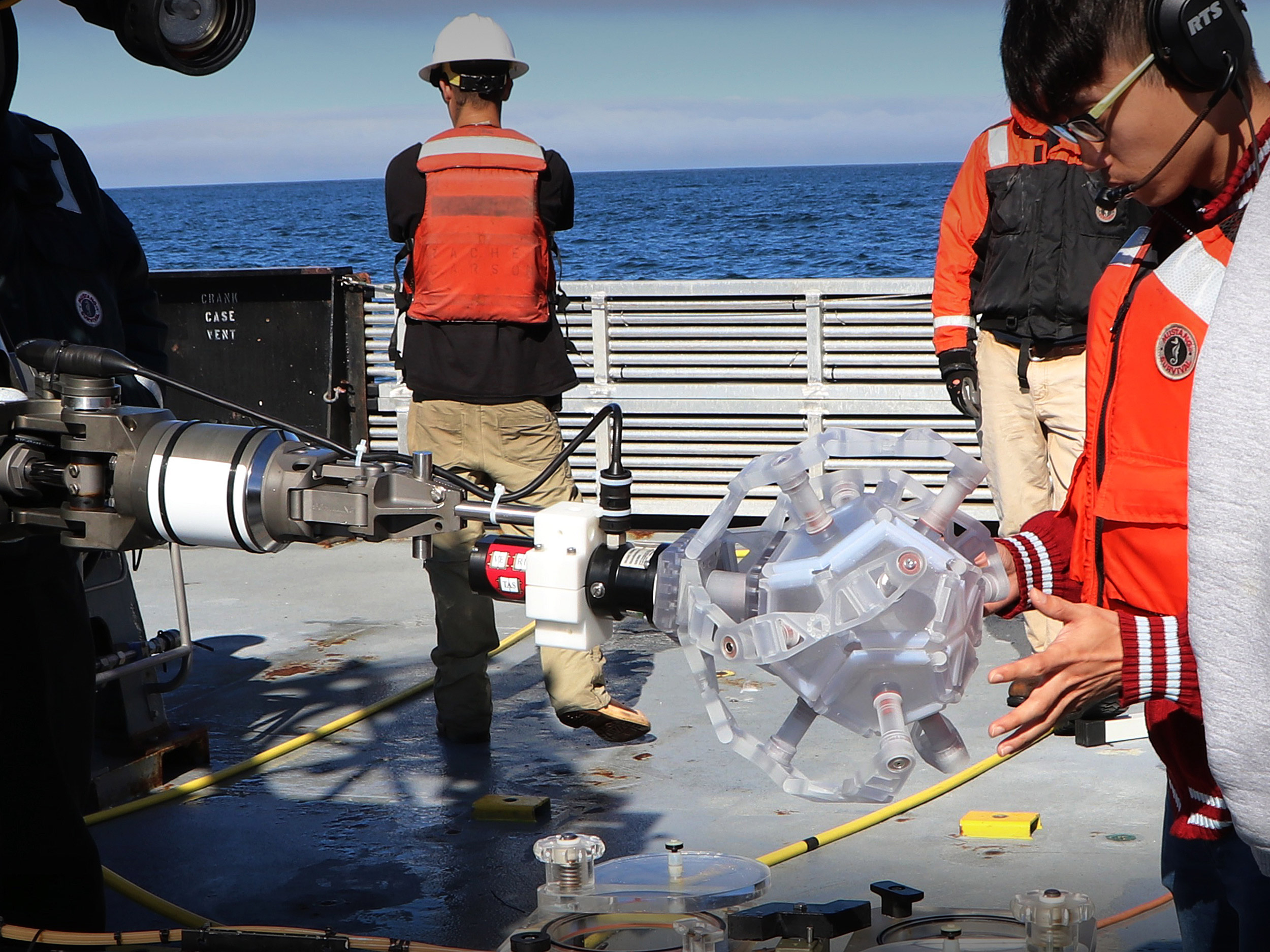

The rotary-actuated dodecahedron (RAD) sampler has five origami-inspired “petals” arranged around a central point that fold up to safely capture marine organisms, like this jellyfish.

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Folding polyhedron sampler enables easy catch and release of delicate underwater organisms

The open ocean is the largest and least-explored environment on Earth. It is estimated to hold up to a million species that have yet to be described. However, many of those organisms — like jellyfish, squid, and octopuses — are soft-bodied and difficult to capture for study with existing underwater tools, which too frequently damage or destroy them.

Now, a new device developed by researchers at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute, John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study safely traps delicate sea creatures inside a folding polyhedral enclosure and lets them go without harm using a novel, origami-inspired design. The research is reported in Science Robotics.

“We approach these animals as if they are works of art: Would we cut pieces out of the ‘Mona Lisa’ to study it? No — we’d use the most innovative tools available. These deep-sea organisms, some being thousands of years old, deserve to be treated with a similar gentleness when we’re interacting with them,” said collaborating author David Gruber, who is a 2017‒2018 Radcliffe Fellow, National Geographic Explorer, and professor of biology and environmental science at Baruch College, CUNY.

The idea to apply folding properties to underwater sample collection began in 2014 when first author Zhi Ern Teoh took a class from Chuck Hoberman, a Wyss associate faculty member and Pierce Anderson Lecturer in Design Engineering at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, about creating folding mechanisms through computational means. “I was building microrobots by hand in graduate school, which was very painstaking and tedious work, and I wondered if there was a way to fold a flat surface into a 3-D shape using a motor instead,” said Teoh, a former postdoctoral fellow at the Wyss Institute in the lab of Robert Wood; he is now an engineer at Cooper Perkins.

A fellow member of the Wood lab at the time, Brennan Phillips (now assistant professor of ocean engineering at the University of Rhode Island), saw Teoh’s design and suggested he adapt it to capture sea creatures, which are notoriously difficult to grab with existing underwater equipment that is largely designed for the rough work of ocean mining and construction.

The device Teoh built consists of five identical 3-D-printed polymer “petals” attached to a series of rotating joints that are linked together to form a scaffold. When a single motor applies torque to the point where the petals meet, it causes the entire structure to rotate about its joints and fold up into a hollow dodecahedron (like a 12-sided, almost-round box), earning it the name of Rotary Actuated Dodecahedron (RAD). The folding is entirely directed by the design of the joints and the shape of the petals themselves; no other input is required.

The team tested the RAD sampler at Mystic Aquarium in Mystic, Conn., and successfully collected and released moon jellyfish underwater. After making modifications to the sampler so it could withstand open-ocean conditions, they mounted it on an underwater remotely operated vehicle (ROV) provided by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Monterey, Calif., and tested it in the field at depths of 500‒700 meters (1,600‒2,300 feet) using the ROV’s manipulator arm and human-controlled joystick to operate the sampler. The team was able to capture soft organisms like squid and jellyfish in their natural habitats, and release them without harm.

“The RAD sampler design is perfect for the difficult environment of the deep ocean because its controls are very simple, so there are fewer elements that can break. It’s also modular, so if something does break, we can simply replace that part and send the sampler back down into the water,” said Teoh. “This folding could also be well-suited to be used in space, which is similar to the deep ocean in that it’s a low-gravity, inhospitable environment that makes operating any device challenging.”

Teoh and Phillips are currently working on a more rugged version of the RAD sampler for use in heavier-duty underwater tasks, like marine geology, while Gruber and Wood are focusing on further refining the sampler’s delicate abilities. “We’d like to add cameras and sensors to the sampler so that, in the future, we can capture an animal, collect lots of data about it — like its size, material properties, and even its genome — and then let it go, almost like an underwater alien abduction,” said Gruber.

“Our group’s collaboration with the marine biology community has opened the door for the fields of soft robotics and origami-inspired engineering to apply those technologies to solve problems in an entirely different discipline, and we are excited to see the ways in which this synergy creates novel solutions,” said Wood, who is a founding core faculty member of the Wyss Institute, the Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at SEAS, and also a National Geographic Explorer.

Additional authors of the paper include Kaitlyn Becker, Griffin Whittredge, and James Weaver from the Wyss Institute and SEAS.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences.