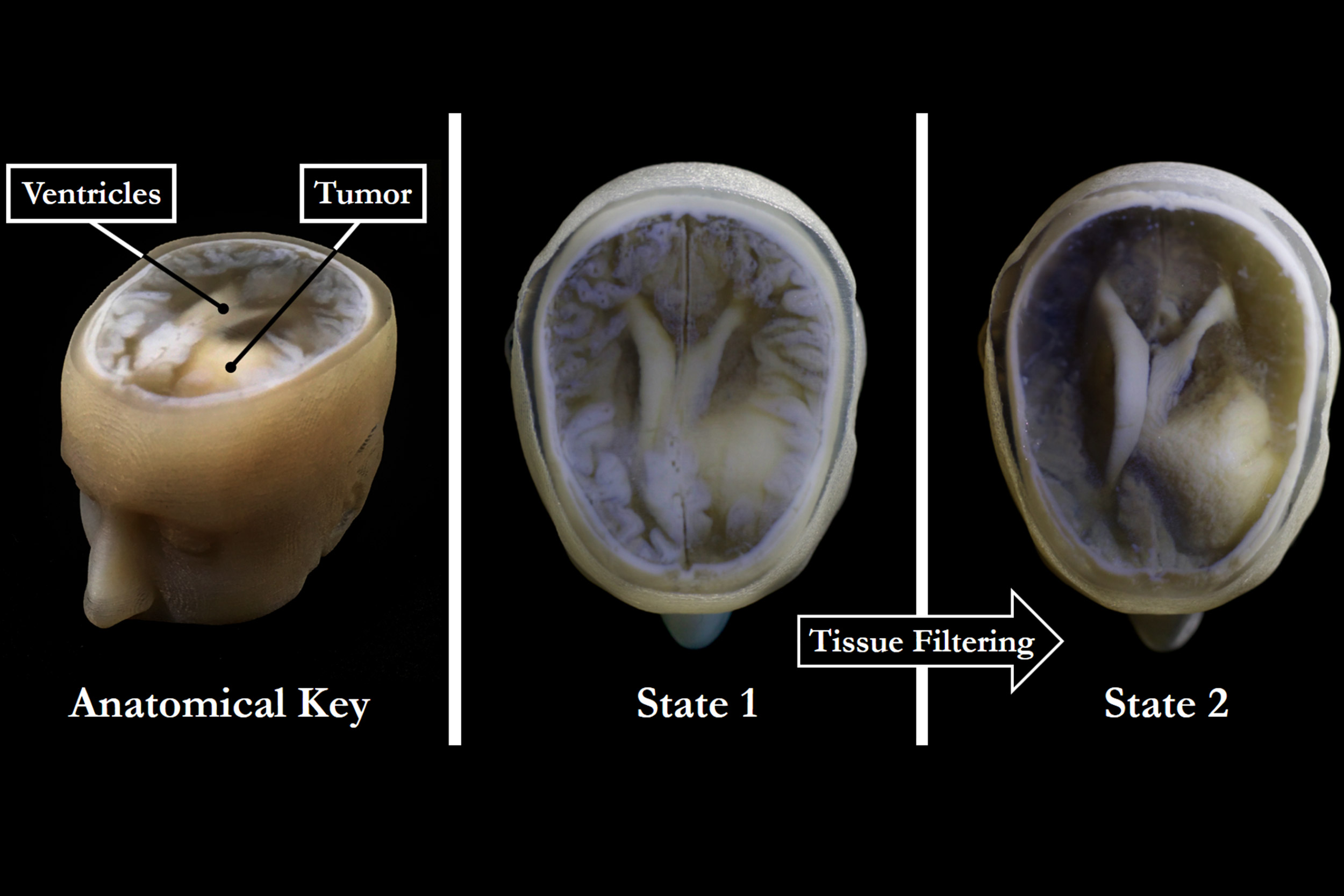

With the new 3-D technology, extraneous tissues can be removed to reveal the desired underlying structures (right) without sacrificing the resolution or intensity gradients present in the native imaging data (left and center).

Credit: James Weaver and Steven Keating/Wyss Institute

Creating piece of mind

New 3-D printing technique enables faster, better, and cheaper models of patient-specific medical data for research and diagnosis

What if you could hold a physical model of your own brain, accurate down to its every unique fold? That’s just a normal part of life for Steven Keating, who had a baseball-sized tumor removed from his brain at age 26 while he was a graduate student in the MIT Media Lab’s Mediated Matter group.

Curious to see what his brain looked like before the tumor was removed, and with the goal of better understanding his diagnosis and treatment options, Keating collected his medical data and began 3-D printing his MRI and CT scans. He found the existing models prohibitively time-intensive and cumbersome, and said they failed to accurately reveal important features of interest. So Keating reached out to some of his group’s collaborators, including members of the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, who were exploring a new method for 3-D printing biological samples.

“It never occurred to us to use this approach for human anatomy until Steve came to us and said, ‘Guys, here’s my data, what can we do?’” said Ahmed Hosny, who was a research fellow with the Wyss Institute at the time and is now a machine learning engineer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

The result of that impromptu collaboration is a new technique that allows images from MRI, CT, and other medical scans to be converted easily and quickly into physical models with unprecedented detail.

The collaborators included James Weaver, senior research scientist at the Wyss Institute; Neri Oxman, director of the MIT Media Lab’s Mediated Matter group and associate professor of media arts and sciences; and a team of researchers and physicians at several other academic and medical centers in the U.S. and Germany. The research is reported in the journal 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing.

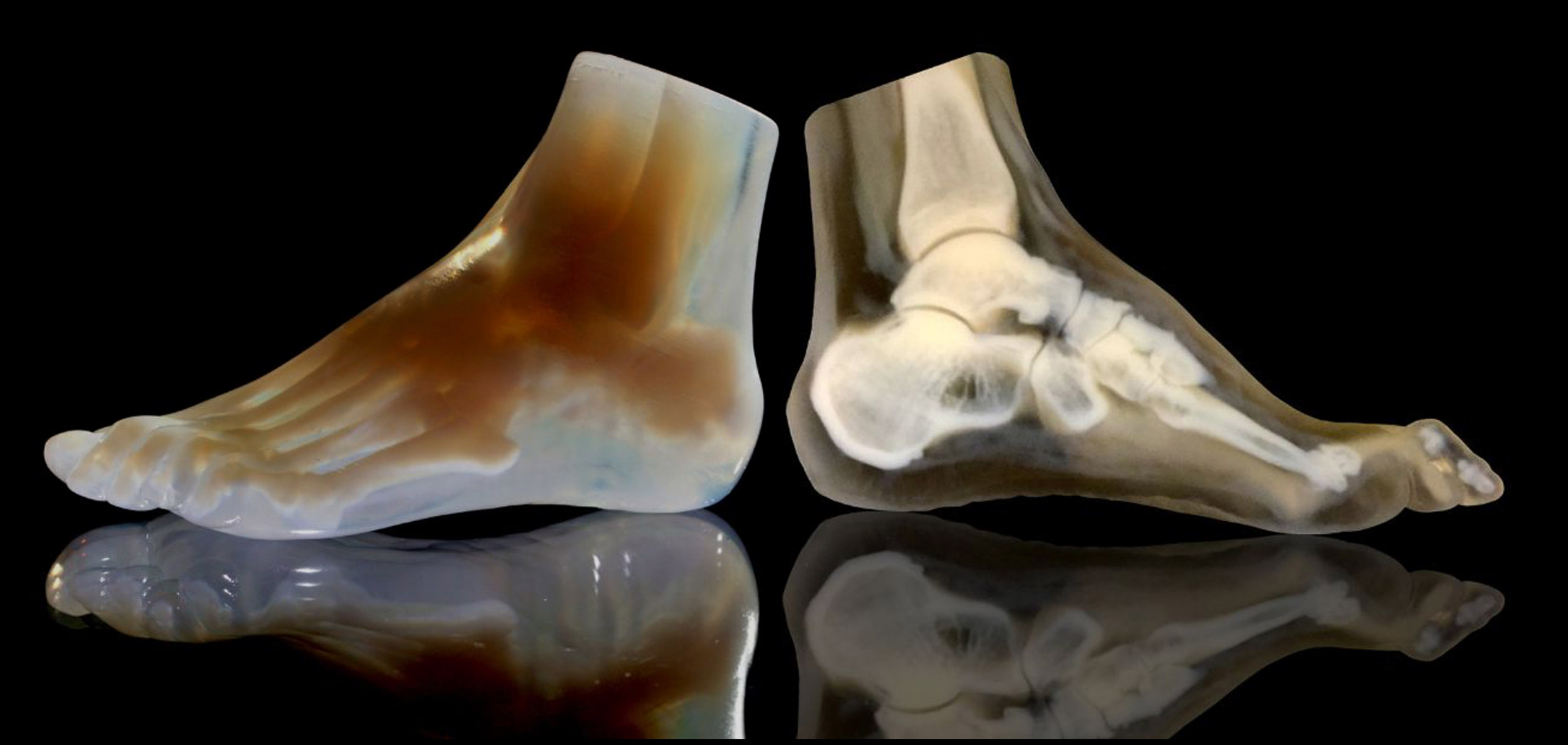

A 3-D-printed foot model (left) and its cross section (right) clearly reveal the intricate internal architecture of the different bone types, as well as the surrounding soft tissue.

Credit: Steven Keating and Ahmed Hosny/Wyss Institute

“I nearly jumped out of my chair when I saw what this technology is able to do,” said Beth Ripley, an assistant professor of radiology at the University of Washington and clinical radiologist at the Seattle VA, and co-author of the paper. “It creates exquisitely detailed 3-D-printed medical models with a fraction of the manual labor currently required, making 3-D printing more accessible to the medical field as a tool for research and diagnosis.”

Imaging technologies like MRI and CT scans produce high-resolution images as a series of “slices” that reveal the details of structures inside the human body, making them invaluable for evaluating and diagnosing medical conditions. Most 3-D printers build physical models in a layer-by-layer process, so feeding them layers of medical images to create a solid structure is an obvious synergy between the two technologies.

However, there is a problem: MRI and CT scans produce images with so much detail that the object(s) of interest need to be isolated from surrounding tissue and converted into surface meshes in order to be printed. This is achieved via either a very time-intensive process called “segmentation,” in which a radiologist manually traces the desired object on every single image slice (sometimes hundreds of images for a single sample), or an automatic “thresholding” process in which a computer program quickly converts areas that contain grayscale pixels into solid black or solid white pixels, based on a shade of gray that is chosen as the threshold between the colors. However, medical imaging data sets often contain objects that are irregularly shaped and lack clear, well-defined borders; as a result, auto-thresholding (or even manual segmentation) often exaggerates or understates the size of a feature of interest and washes out critical detail.

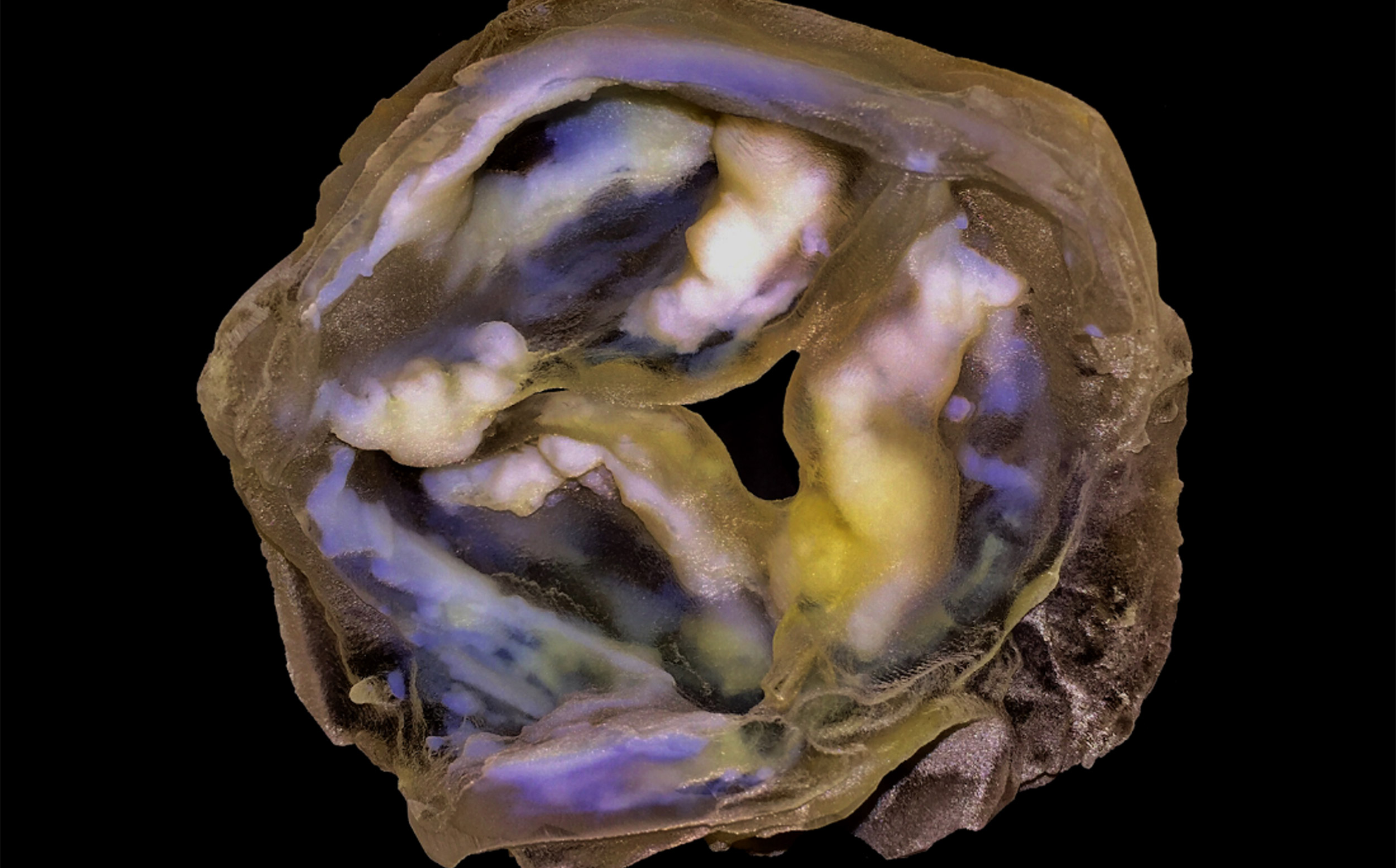

A 3-D-printed multi-material model of a calcified heart valve shows hard calcium deposits (white) with fine-scale gradients in mineral density that are impossible to fully capture using conventional biomedical 3-D printing approaches.

Credit: James Weaver and Ahmed Hosny/Wyss Institute

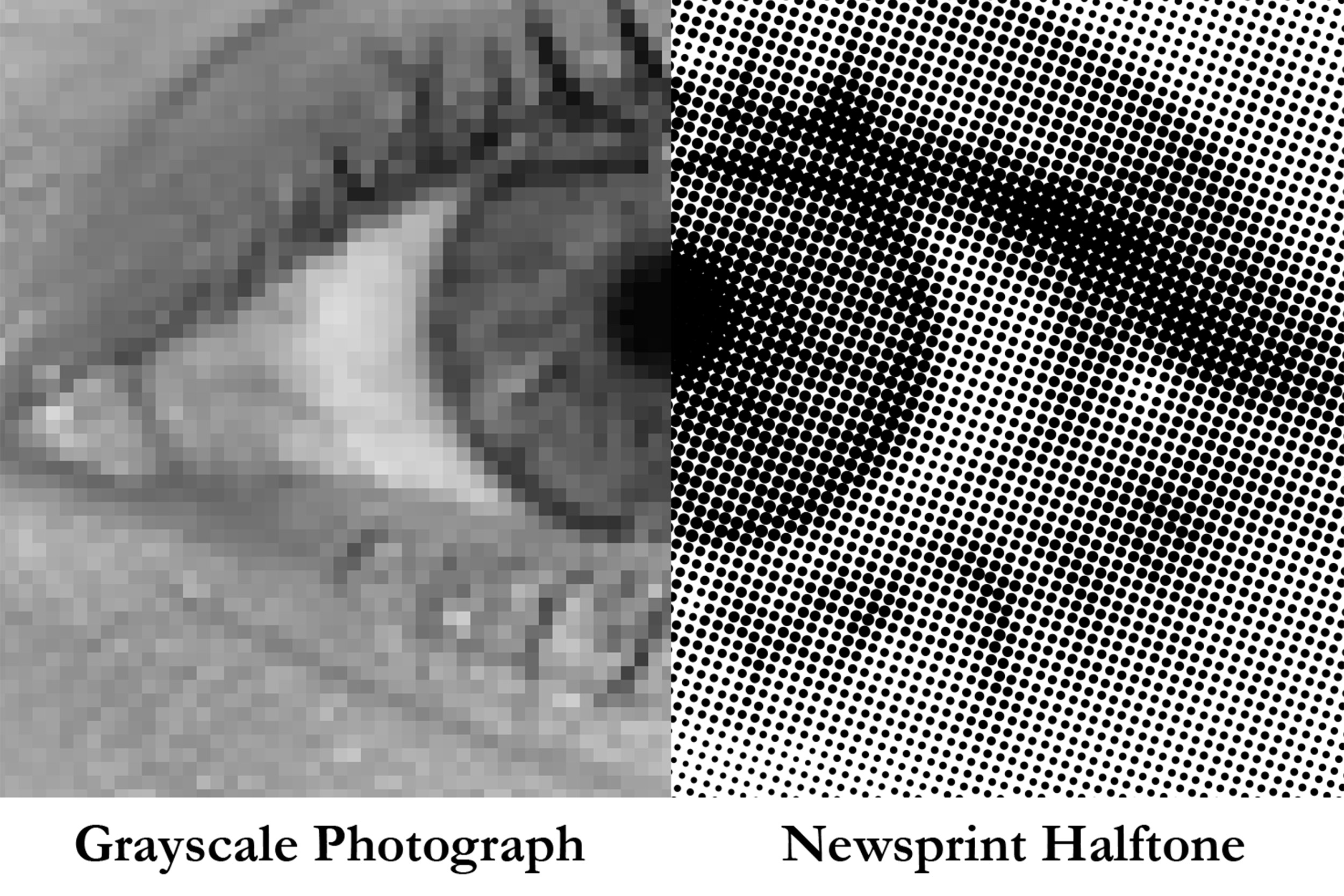

The new method described in the paper gives medical professionals the best of both worlds: a fast and highly accurate method for converting complex images into a format that can easily be 3-D printed. The key lies in printing with dithered bitmaps, a digital file format in which each pixel of a grayscale image is converted into a series of black and white pixels, and the density of the black pixels is what defines the shades of gray, rather than the pixels themselves varying in color.

Similar to the way images in black-and-white newsprint use varying sizes of black ink dots to convey shading, the more black pixels that are present in a given area, the darker it appears. By simplifying all pixels from various shades of gray into a mixture of black or white pixels, dithered bitmaps allow a 3-D printer to print complex medical images using two different materials that preserve all the subtle variations of the original data with much greater accuracy and speed.

Unlike grayscale photographs, which require several shades of gray to convey gradients (left), halftones (common in newsprint images) can preserve grayscale intensity gradients using only a single color of ink (right). A similar approach was used for processing the image stacks for the 3-D printed models described in the paper.

Credit: James Weaver/Wyss Institute

The team of researchers used bitmap-based 3-D printing to create models of Keating’s brain and tumor that faithfully preserved all the gradations of detail present in the raw MRI data down to a resolution that is on par with what the human eye can distinguish from about 9‒10 inches away. Using this same approach, they were also able to print a variable stiffness model of a human heart valve using different materials for the valve tissue and the mineral plaques that had formed within it, resulting in a model that exhibited mechanical property gradients and provided new insights into the plaque’s actual effects on valve function.

“Our approach not only allows for high levels of detail to be preserved and printed into medical models, but it also saves a tremendous amount of time and money,” said Weaver, who is the corresponding author of the paper. “Manually segmenting a CT scan of a healthy human foot, with all its internal bone structure, bone marrow, tendons, muscles, soft tissue, and skin, for example, can take more than 30 hours, even by a trained professional — we were able to do it in less than an hour.”

The researchers hope that their method will help make 3-D printing a more viable tool for routine exams and diagnoses, patient education, and understanding the human body. “Right now, it’s just too expensive for hospitals to employ a team of specialists to go in and hand-segment image data sets for 3-D printing, except in extremely high-risk or high-profile cases. We’re hoping to change that,” said Hosny.

Keating, who has become a passionate advocate of efforts to enable patients to access their own medical data, still 3-D prints his MRI scans to see how his skull is healing and check on his brain to make sure his tumor isn’t coming back. “The ability to understand what’s happening inside of you, to actually hold it in your hands and see the effects of treatment, is incredibly empowering,” he said.

This work was supported by a grant from the Human Frontier Science Program, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz-Preis 2010.