Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

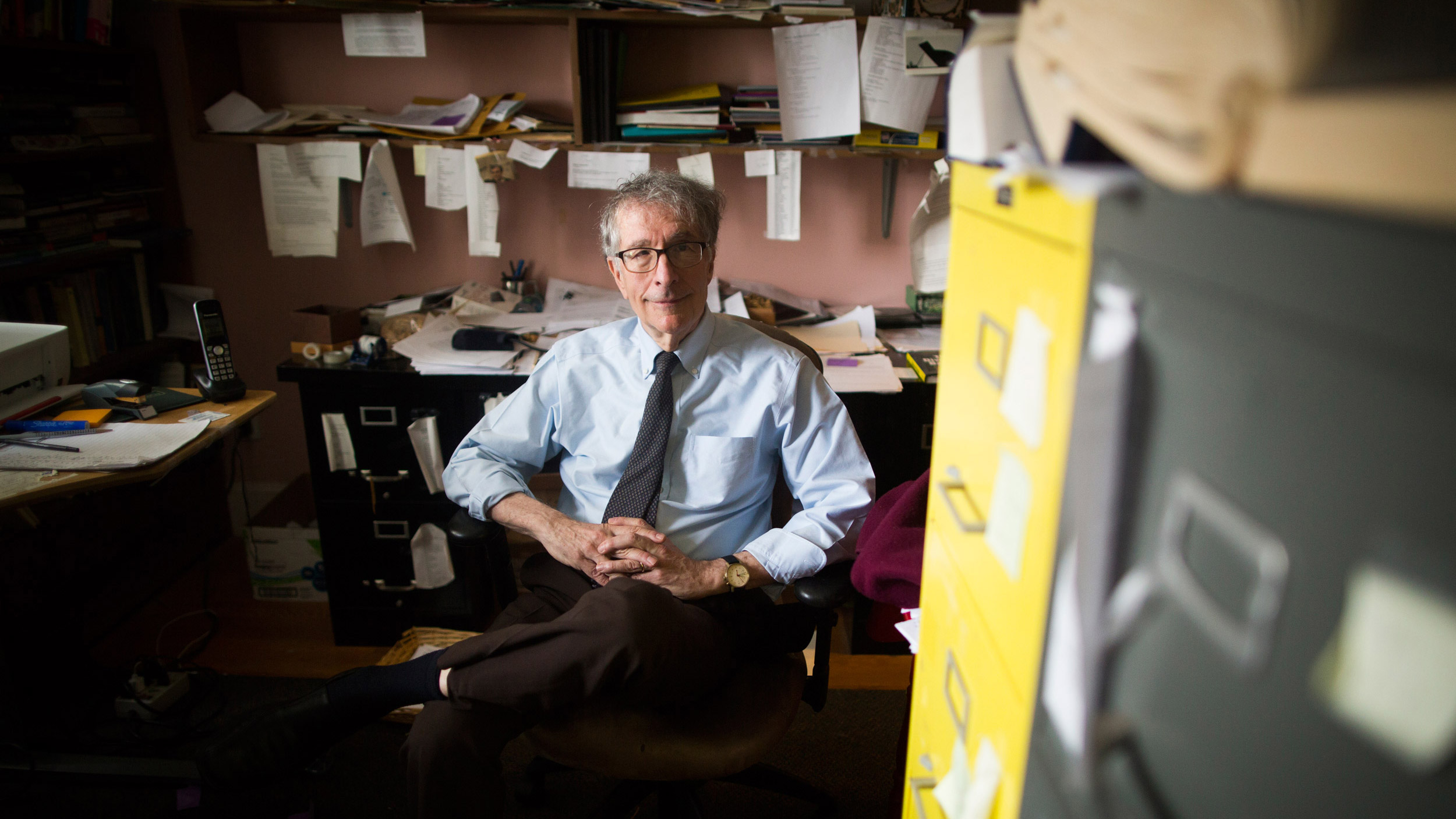

‘The greatest gift you can have is a good education, one that isn’t strictly professional’

In a life of multiple pursuits, Howard Gardner has remained a student above all else

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, after he had worked with brain-damaged hospital patients and healthy schoolchildren, Howard Gardner developed a theory that changed the way people study intelligence and transformed the fields of psychology and education.

With his “theory of multiple intelligences,” Gardner challenged the notion of a singular entity of mind, mostly genetic, and instead put forward the idea that all of us possess different types of intelligences, including linguistic, spatial, and musical.

Gardner, a 1981 MacArthur “genius” fellow, would branch out to write books and formulate ideas in a range of other fields, including ethics. He is the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and an adjunct professor of psychology and senior director of Project Zero.

Can you tell me about your childhood?

I grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. It was once a booming anthracite coal town, but by the time I was born, in the early 1940s, it was already becoming a depressed area. I had an uneventful childhood; probably the biggest impact came from events that my parents had gone through.

Hilde and Ralph were German Jews who grew up early in the 20th century and expected to spend the rest of their lives in Germany. They lived like middle-class bourgeoisie until Hitler came to power in 1933. In 1934, they moved to Italy to escape Hitler, and in 1935 they had a child named Erich.

They were making a life for themselves in Italy, but when Hitler made a pact with Mussolini, they decided they’d better move back to Germany and try to flee the continent. From 1936 through 1938, my father made several trips back and forth to the United States from Germany, trying to get people to sign an affidavit so that the family could move to America and not be considered a financial burden on the state. Finally, in 1938, my father secured the needed affidavit. My mother and Erich, then age 3, who were effectively being held hostage by the Germans, were allowed to travel with my father to the United States.

The family arrived in New York City with literally $5 in their pockets on Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, when many of their relatives were injured or killed. They had made it here in the nick of time. And then, in 1943, when my mother was pregnant with me, their 8-year-old son Erich died in a tragic sleigh-riding accident. My parents told me, when I was much older, that if my mother hadn’t been pregnant with me, they would have killed themselves because they had effectively lost everything.

I read that you grew up not knowing you had a brother.

In those days, most parents didn’t tell kids things that upset them and that might upset their children. My parents never talked about the Holocaust, and although there were photographs of my brother around the house, they’d say that he was a kid from the neighborhood. At that time it wasn’t understood that children almost always figure things out, one way or the other, and children suspect when something is being withheld from them. I had always wondered why my parents displayed a photograph of a child from the neighborhood.

When I was 10 or 11, I found some clippings about his death. My major reaction was annoyance at the fact that my parents hadn’t told me about something so important in their lives. Now, of course, I understand they probably couldn’t talk about it. Just as with the Holocaust, it was so complicated. There were so many relatives and friends who didn’t escape in time and were killed. But somehow not being apprised of something so important within the nuclear family was a source of disappointment or irritation. But I don’t recall an explosion.

“In my very first week at Harvard, I stood on the steps of Widener Library and I felt the whole world was open to me.”

Can you tell me about your parents? Did they put a lot of pressure on you?

My parents didn’t have higher education, but they were very successful. My father was the co-owner of a company that sold stoves and ovens. His father had died when he was 16, and that meant he had to take over his father’s company. That’s why he couldn’t go to college. My mother was training to be a kindergarten teacher, but when they left Germany for the first time, everything stopped.

Hilde was a remarkable woman. She never had a paid job as far as I know, but she was a very dedicated public servant in Scranton. She was a leader in many organizations and she was chosen as the woman of the year in the city. She was what author Malcolm Gladwell calls a “connector,” someone who is oriented to the world and connects people with others whom they would like to or ought to meet. And even though I’m much less social and much more of an introvert than my mother, I also am a connector.

And my father, Ralph, during wartime and thereafter, he was like the general of an army without weapons. There were surviving relatives and friends and associates all over the world, in a kind of a diaspora, and it was my father’s job, because he was the youngest and most capable person, to keep track of where everybody was and to help out in whatever way was possible. Whenever people came to the United States, they’d stay at our home.

He was a very shrewd businessman, to the extent that when he was 58, he was able to retire, with his three partners, who were his cousins. I got some business sense from my father and also from my maternal grandfather, who was a hops merchant and who miraculously was able to relaunch his business after World War II.

What kind of child were you?

I think that even without the event of a sibling who died tragically, which in essence I was a replacement for, it was very clear to me that, being the oldest of 15 or 20 cousins, there was a lot riding on me to become successful. I was lucky to be the proverbial bright Jewish kid. I was very accomplished in school. I was an early reader and writer, and when I was in second grade, I produced a newspaper. I don’t think anybody cared about it — just like now I blog and I don’t think anybody cares about it. I did not concern myself with whether I had readers. The fun was writing a newspaper, setting the type, and watching the pages emerge from the simple printer.

My family was oriented toward achievement, putting a lot of eggs in the firstborn’s basket. But because my parents themselves didn’t have higher education, they didn’t try to maneuver me to do A rather than B. They trusted my judgment on many matters.

Gardner playing the piano.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

You were a serious piano player and a Boy Scout.

Until I was 12, playing piano was a very important part of my day. When I was 12, I had a fateful conversation with one of my piano teachers. He said, “Well, I taught you all I can teach you. And now you have to go to New York and you need to practice three hours a day.” I made a decision that I didn’t want to schlep to New York or practice three hours a day, and so I quit. In high school and graduate school, I’d teach piano. I didn’t have any training, but I was good enough to be able to teach a few students.

I was an Eagle Scout at quite a young age. What is interesting about that is that I’m not particularly athletic or outdoorsy — I didn’t particularly like summer camp although I went for seven years. But I was an achiever in the sense that I wanted to do what was required of me. I was also a champion marcher. I knew how to follow orders. This is also a theme throughout my life.

I wanted to prove I could do something even if I really didn’t want to do it. As a youth, I was the proverbial future lawyer because I was the Jewish boy who hated the sight of blood. Everybody said to me that I was going to be a lawyer, so I assumed that’s what I’d be. And when I went to college, that’s what I assumed I’d be. But I took pre-med courses, and as late as my junior year, I went to Stanford to talk to the admissions director — not because I wanted to become a doctor, or, for that matter, a lawyer, but because I wanted to tell my parents and the world I could do that if I wanted to.

What were your impressions when you first came to Harvard, in 1961?

When I came to Harvard College, I met plenty of people who knew more than I did. In everything I did, including playing the piano, there were people better than I was, and that was good. You shouldn’t think that because you are a big fish in Scranton, that’s going to happen indefinitely. But what I remember is that, in my very first week at Harvard, I stood on the steps of Widener Library and I felt the whole world was open to me. Harvard gave me chances to pursue my curiosity, my appetite for new knowledge. And I guess — I’ve never put it this way before — I didn’t think that there was anything holding me back. That’s a wonderful feeling.

“As for interpersonal intelligence, the ability to communicate effectively and empathize with others, I quip that I’m still working on it.”

What courses had a big influence on you?

I may have audited more courses than anyone in the history of Harvard College! I took or audited all kinds of courses, but I followed my own path. I wanted to show that I could do medicine or law.

I thought I’d become a history major. I took history courses during my freshman year. As a 19-year-old, I was fascinated by the Crusades and the Industrial Revolution, but I didn’t care about how historians wrote about it. And so when the history tutorial in sophomore year was focused on historiography, I got cold feet.

I was also interested in psychology. I had a very insightful teacher who said to me, “You seem to be interested in psychology and sociology; you should major in social relations.” Nobody below a certain age knows what the field of “social relations” is, but it was a major, a concentration — a combination of sociology, anthropology, and psychology. It was developed at Harvard after World War II, and the founders of that field were still alive and teaching when I was a freshman. It didn’t have much prestige, in part because it was seen as an easy major.

But I was interested in it. I majored in soc-rel, and literally I never took a psychology course but I knew that I was interested in social science. And that’s exactly what I became. I’m a social scientist, quantitative and qualitative, but from my work over the last few decades, you wouldn’t know whether I studied sociology, anthropology, or psychology.

At first I thought I’d study clinical psychology as a graduate student, but I went to England on a fellowship and before I had packed my bags, by chance I met Jerome Bruner, a renowned and charismatic psychologist. I became interested in cognitive psychology. Bruner also introduced me to my future wife, Judy Krieger, who was coming to graduate school as a psychologist. On our honeymoon, in June 1966, we went to Geneva to meet Jean Piaget, the Swiss psychologist. By that time, I wanted to do cognitive developmental psychology in the Piaget-Bruner tradition.

Tell me more about your studies and your research, and how they led you to become interested in the human mind.

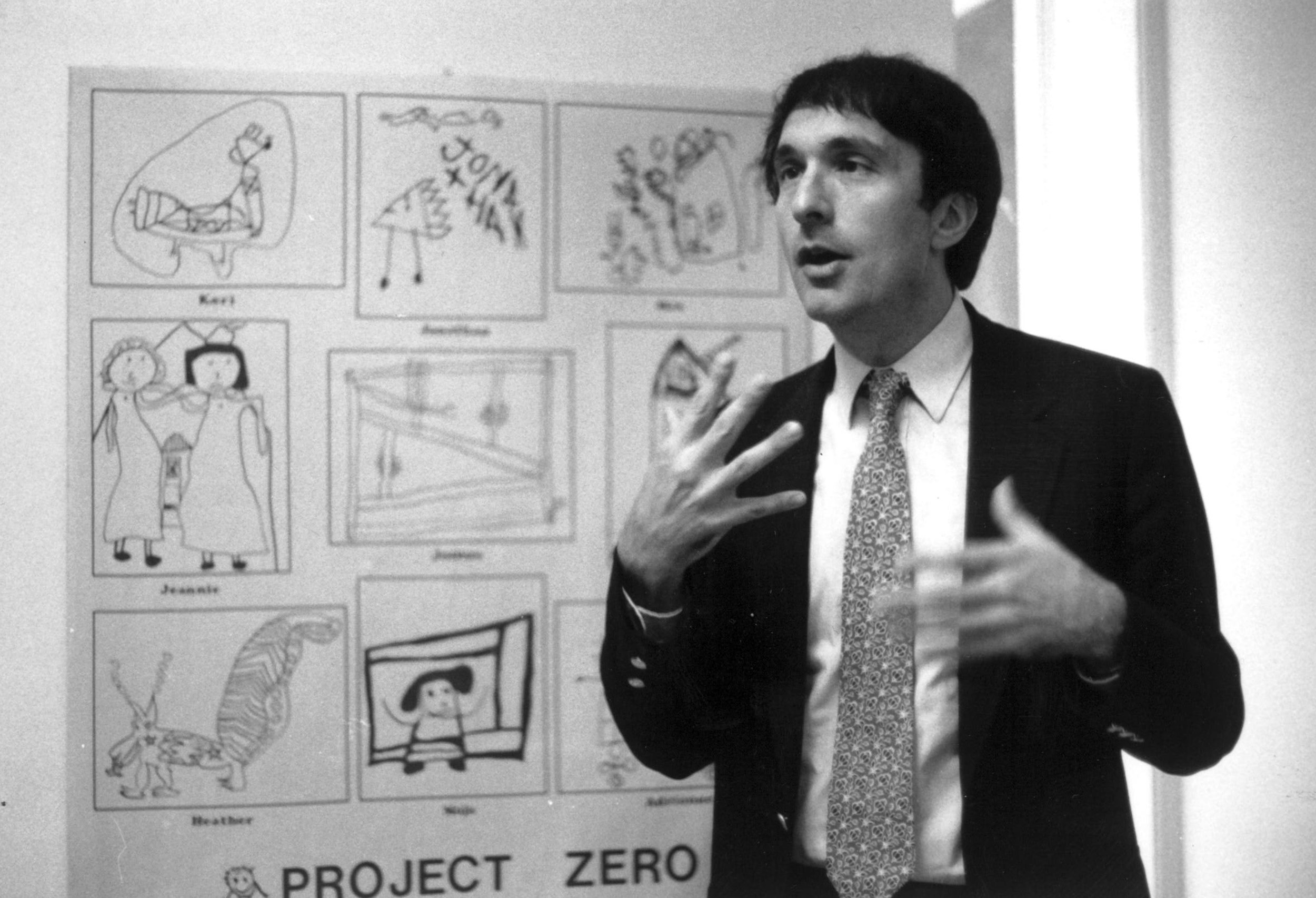

Gardner is pictured in 1988, five years after the publication of “Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences.”

Courtesy of Howard Gardner

I took an unusual career path. Shortly after I commenced graduate studies in developmental psychology, I began to work as a research assistant at Project Zero, a just-launched research organization in education created by a brilliant philosopher, Nelson Goodman. While at Project Zero, I began to do studies of children’s artistic development. Piaget had focused on the development of scientific thinking, and so I decided instead to focus on the development of artistic thinking, doing studies with kids and the arts. Thus were combined my interests in human development and my interests in music and other art forms.

After receiving a doctorate in developmental psychology, I got a post-doctoral fellowship to work at the Boston Veterans Administration Hospital, where I saw brain-damaged patients. I was inspired by a great teacher, Norman Geschwind, a neurologist who said we could learn about the mind from studying brain damage.

And so, every day, almost by chance, I’d be working at the VA with brain-damaged patients in the morning, and in the afternoon I’d be doing studies with kids at Project Zero. This was a really transformative experience. Seeing dozens of brain-damaged patients, I realized that the notion of intellect being one thing didn’t make any sense. The first thing that strikes you about brain damage is that it is quite selective. Some patients had lost their language abilities but they were very musical or vice versa. I also worked with kids, and some of them were good in writing, others were good in drawing, and some others in dancing or painting. And people can be very good in music but they can’t write a coherent sentence — or vice versa.

All these experiences chipped away at the notion of intelligence as being one, singular, even though I never thought about it explicitly. And then the dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education asked me to co-direct a “project on human potential.” I had already outlined my third book, directed at the general reader, called “Kinds of Minds.” I was going to write about the different kinds of minds that I observed at the VA hospital and in my encounters with children. (By then, Judy and I had three of our own: Kerith, Jay, and Andrew.)

That was the material for “Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences,” which came out in 1983.

I have never been able to reconstruct when I made the fateful decision not to call these abilities, talents, or gifts, but rather to call them “intelligences.” Because if I had called them anything else, I would not be well known in different corners of the world and journalists like you wouldn’t come to interview me. It was picking the word “intelligence” and pluralizing it.

Almost every computer program underlines the word intelligences because it’s supposed to be singular, not plural. My computer has learned it’s plural when I use it. But by coining “multiple intelligences,” I picked a fight with the Mensa crowd, and with psychologists like Richard Herrnstein, who wrote that IQ is largely inherited and that status in life and work is largely determined by IQ. That’s also what shifted me from being a standard experimental psychologist to becoming more interested in education. And my career can be divided loosely into three foci: psychology, education, and now ethics.

Your theory of multiple intelligences was embraced by educators but not by psychologists. Did that surprise you?

Psychologists have a certain way of studying intelligence. They have a certain notion of what intelligence means and how to test for it. I was kind of a bull in a china shop when I came out with my theory. Psychologists never liked my ideas. Educators found that it spoke to them, and I became a kind of modest celebrity in education. Accordingly, I’ve become more like an “educationalist,” a word favored by the British.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

According to your theory, people have different kinds of intelligences: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal. Which do you have?

I’m a perfectly good student so I have the requisite linguistic and logical intelligences. I definitely have a lot of musical intelligence. As for interpersonal intelligence, the ability to communicate effectively and empathize with others, I quip that I’m still working on it. I wouldn’t call myself wise, but at age 74, I’m much more able to give people the advice they need or want to hear than I was 20 or 30 years ago. I have good intrapersonal intelligence because I always had a sense of what sort of things I could do particularly well and what sort of things I couldn’t. That doesn’t mean I didn’t do things that I couldn’t do well, but I realized I had to work harder at them.

I’m quite sure I would perform below average in kinesthetic intelligence, the ability to excel in physical activities such as dance or sports. I blame my parents to some extent because they were very protective of me, having lost their firstborn in a freak accident. I didn’t know how to ride a bike until I was in college because they didn’t want to lose a second child. Whatever bodily-kinesthetic intelligence I may have had was completely quashed, except for drilling, soldier style, because I could follow commands, and digital dexterity, from decades of typing and playing the piano. I don’t have much spatial intelligence, but now with various GPS systems, that can happily be supplemented with technology. That is true about any intelligence.

I also think that personal intelligences are easier to keep improving than logical-mathematical intelligence and musical intelligence, both of which are better off if you start early. That’s why we have prodigies in those areas.

I should mention that my teacher in the realm of giftedness and prodigiousness — and much else! — is my second wife, Ellen Winner, whom I met at Project Zero. We fell in love, were married in 1982, our son Benjamin was born in 1985, and we recently celebrated our 35th anniversary.

Later on, you added to the list of intelligences. Will experts find more in the future?

I don’t think that human intelligence has changed, but there may be ones that I just haven’t studied. There are two other candidate intelligences that I’ve written about. One is “pedagogical,” being able to teach, because we’re the only species that teaches, and as young as 2 or 3, kids can already teach. And the second I call “existential,” a big word, for the ability to raise and ponder interesting questions, which as far as we know no other species can do.

As a scholar, I have lost interest in multiple intelligences even though 80 percent of my mail is still about it. Ninety percent of my speaking invitations are about multiple intelligences and I maintain a website.

But all bets are off because this is the first time in history that we’re going to be able to affect the brain directly, to affect genetics directly, and of course, create artificial intelligences, which we either interact with, internalize, or merge with our brains. At present there are many things we can’t imagine because we’re limited by our evolved brains. But with technology, we — or the technology! — might create all sorts of new intelligences. Until 15 years ago, that would have been science fiction, but it’s not science fiction anymore.

“At present there are many things we can’t imagine because we’re limited by our evolved brains. But with technology, we — or the technology! — might create all sorts of new intelligences.”

More recently, you have said that intelligence is important, but ethics is even more important — that what we do with our intelligence, the purpose, is what matters. Could you expand on this?

I am fortunate to have the example of my parents, who were deeply ethical people. They did not do anything unethical; they wouldn’t even consider it.

In my own case, I was pretty judgmental about people who cross lines, and I always have been. I hope that other people tell me when I do so. But ethics was not something I was interested in as a scholar. I became interested in the purpose of our minds and our lives, in how intelligences and morality can work together to yield the kind of persons we admire and the kind of society in which we would like to live.

More generally, as a scholar, I work at Project Zero and honor its motto — we develop ideas and give them a push in the right direction. My competitive advantage has been developing ideas and concepts, but ever since becoming more than an educationalist, my work is not just developing ideas, but trying to think about what to do with the ideas. In fact, through The Good Project, we’ve just embarked on a project to develop some tools to see whether secondary schools are achieving their ethical goals.

You have written more than 20 books. Which one are you most proud of?

The one I like the best is called “Creating Minds.” It came out in 1993. I like it because I had the opportunity to study seven great creators in great depth. I love learning about other people’s lives. That is the book I had the most fun doing.

What about the book on multiple intelligences?

Well, I’m not really proud of it. It made me a well-known scholar, and it will be on my tombstone, so to speak.

If I have to say which books make me feel proud, it’d have to be where I made the biggest stretch. But there is a problem here. In a way, books are like children. You feel most empathy for the ones that are neglected. I published a book in 2011 called “Truth, Beauty and Goodness Reframed.” It didn’t sell much and most people don’t know about it, but I think it’s incredibly relevant today, and it got a wonderful review by a philosopher, Alan Ryan, in The New York Review of Books. That meant an enormous amount to me.

Now I teach a course called “Truth, Beauty and Goodness: Three Fundamental Educational Values.” After Nov. 8, 2016, the course changed totally. The idea of “truth” as a universal aspiration didn’t work anymore. It became clear that many people are very happy living with a deficient sense of truth — not knowing, not caring. A large part of the population, people who should know better and people who don’t, don’t actually think truth matters, and that changes everything.

I read that you consider Mahatma Gandhi one of your heroes.

Gandhi understood that we live in a world where for the first time in human history, someone could destroy the world. That wasn’t true during the Punic Wars or during the Crusades or even the World Wars. As a result of this unprecedented situation, said Gandhi, we have to learn to dispute, argue in a nonviolent way. That’s a very hard lesson to learn, but it inspired Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela, and anybody nowadays who protests injustice in a nonviolent way is really taking a leaf from Gandhi.

I recommend his autobiography, “The Story of My Experiments With Truth.” Gandhi was supercritical of himself. Everything he did, he looked back and criticized and tried to do better. I don’t pretend to compete with him, but I try to learn from what I do wrong and I try to get other people to learn from what they do wrong. That’s how Gandhi lived every day — how could I do better, what can I learn from this? In addition to being an international giant, Gandhi gave us an example of a healthy and practical way to think about and lead your own life.

Gardner, third from left, poses with fellow Harvard graduates in 1965.

Courtesy of Howard Gardner

Can you tell us about regrets?

I have tried to be a good husband and a good father but I went through a difficult divorce when I was young, and it caused pain. I regret that. I have tried my best to make up for it. That’s a personal regret.

Professionally, I’ve been fortunate because I came to Harvard many years ago, and I have been able to stay here in various guises. Going to Harvard College, going to a Harvard graduate school, and being on the books for over 55 years, it has been very comfortable for me. There are very few people now my age who have been here their entire lives.

A question I ask myself almost every day is, If I was exactly who I am, would I go into academics today? I have real doubts that I would. And I think it would have been a tragedy for me because I think I’m better suited to do research, teach, mentor, and run a research team than do anything else.

I think there are professional things which I could have done differently and better. And what I tried to do is make amends for it. I’ve tried not to hold grudges. That’s sometimes difficult because you feel you’ve been mistreated, and it’s hard to take responsibility for your own flaws. And you never really know what people think about you.

But I’ve been very moved at the kind and thoughtful things people have said to me. When over 100 of them wrote tributes to me when I turned 70, what really surprised me was that more people wrote about my personal example than about my particular scholarly ideas or books. And that’s not what I would have predicted. We could say that they wrote about “me” rather than about “MI.”

What I tried to give to my doctoral students and to the hundreds of people that have worked with me in Project Zero, over 50 years now, is an example of one way to live a life. It’s about trying to do the right thing and not even think about doing the wrong things. I got that from my parents, and I would like to think that I kept people, besides myself, from doing things which were foolish in retrospect.

I serve on a number of high-profile boards, and I can’t contribute much financially, but sometimes I’m the person who says, Do you have any idea how the rest of the world would think about this? I’m astonished that people don’t think about it. So, yes, I have made lots of mistakes and I’ve possibly hurt some people, but at least I tried to make amends, and I tried to model that as best I can.

What has been the most rewarding part of your academic career?

As an academic, you can work in splendid obscurity. But as compensation, as Henry Adams famously said: A teacher never knows when his or her influence stops. There are things I did 30 years ago I completely forgot about, and they crop up again when I hear from students whom I had long forgotten, “Something you said to me when I was taking your course really changed me.” There is nothing like that.

Having been taught by brilliant teachers such as Erik Erikson, David Riesman, Nelson Goodman, and Jerome Bruner was transformative; it was important for me to be part of that lineage. I am who I am because of my teachers, and I want my students and colleagues to know that. When you go to my office, on the wall are photographs of letters from people such as psychologist Jean Piaget and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. When I was a graduate student, I wrote about them, and then sent them my essay. And to my amazement both scholars sent me letters on the same day! For me, that sends a strong message to a young student, when two people he greatly admires both take the time to write him a substantive letter.

I’ve been able to write a lot. I wrote three books when I was in graduate school, which was very unusual. I’m more a book person than an article person. A role model is Stephen Jay Gould. He was a great scientist and died at a young age. I admire people who take insights from many different fields and put them together in new ways. That is how I fashion myself. I sense what my competitive advantage is, to use a 21st-century phrase. That’s probably an important thing for anybody who is not a polymathic genius: to figure out what you can do relatively better than other people.

And now, as it turns out, and unexpectedly, I’m doing the biggest study of my life. It’s a huge study of undergraduate education, and it’s likely to take seven years. We’re interviewing 2,000 people, 200 in each of 10 schools, and my colleagues and I are trying to figure out how the different stakeholders at 10 very different colleges think about college education. We’re talking to freshmen, seniors, faculty, administrators, parents, alums, trustees, and recruiters. We’re trying to get a 360-degree picture of how all the different stakeholders think about higher education. The data are mostly collected and we’re now trying to make sense of it. Our initial impressions are beginning to appear in a blog called Life-Long Learning.

If you hadn’t become a psychologist-educator, what would you have been?

I think about this a lot. I could have made a living as a mediocre piano player in a bar because I’m good enough and I can play by ear, but I don’t think I would have become a concert pianist. I think I was very shrewd to decide at age 12 that I was going to play just for fun. (And I still do!) It’s conceivable that I could have become a musicologist, somebody who studies music, but I think it was more likely that I would have become an academic, maybe a historian because I like history, possibly a philosopher, possibly a neurobiologist. Those are the things I’m interested in.

I think that if I hadn’t become an academic, I would have become a lawyer. Had I pursued the law, I would have liked to become a judge or a professor, but you can’t count on that. I also could have been a reasonably successful business person. I could have been a management consultant, but I felt very lucky to have picked just the right thing for me, and for not having anybody telling me what to do.

Indeed, I’ve really never had a boss. As a professor I have a dean and a president, but they don’t tell you what to do. Except in 1971, when I applied for a job at Yale (and I didn’t get it), I had never applied for a job.

It’s amazing to go through life, not being born rich, without having to apply for a job, and being able to do what you want. My first and most fervent hope is that young people today would have the chance to do that as well. I worry that may not be a possibility. People have to understand that if you want to have a fulfilling life at work and outside of work, the greatest gift you can have is a good education, one that isn’t strictly professional.

I had 12 friends at Harvard College with whom I was very close. When we graduated in 1965, we all went to a bar — Cronin’s, of blessed memory — and we said, “We should get together in our 25th reunion but one of us will be dead by then.” A few years ago we had our 50th reunion, and everybody is still alive. Out of the 12, 10 did professionally what we wanted to do when we graduated. That is inconceivable now. It was a very different time.

This interview has been edited and condensed.