Jennifer Kotler is a doctoral candidate in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She developed severe ADHD at age 8, and learned to use her disability as a benefit, eventually focusing on public engagement and education around sexual violence.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Ph.D. with ADHD brings can-do focus to science, life

Jennifer Kotler: ‘It’s really difficult to separate your personality, your identity, from your diagnosis’

This is the first in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

In third grade, Jennifer “Jenna” Kotler was perfectly happy counting the tiles in the classroom ceiling instead of doing her work. What she tried hard to do was sit quietly like her classmates in their French-immersion school in Toronto.

Sitting quietly isn’t a requirement at Harvard, a place no one ever expected Kotler to land. At age 8, she was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), a learning disability that can challenge even the most determined student.

“I was not disruptive, never got into physical altercations or had vocal modulation,” Kotler said. “But my third-grade teacher knew I had a learning disorder because I could not do the written work. My mom had to stand behind me with her thumbs in my ears and her hands around my eyes so I could finish a page of multiplication tables.”

Twenty years later, Kotler is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology (OEB) at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. An evolutionary theorist, she uses clinical and genetic studies to reinterpret how humans think about health, disease, and the human evolutionary path, especially as it relates to biological and psychological development.

David Haig, the George Putnam Professor of Biology and Kotler’s doctoral adviser, worked with her to create an interdisciplinary research program that would accommodate her condition. While she doesn’t count the ceiling tiles in her brightly lighted office at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Kotler still spends nearly every waking moment combating her ADHD, which affects both her memory and her personality.

“My brain works differently … I struggle daily with how to be in the workplace and constantly monitor myself,” Kotler said. “I’m really enthusiastic and eager, so I talk a lot, and really loudly. I interrupt a lot, and can be distracting to others. I’m extremely friendly, and tend to come on very strong. It sets you up for a lot of heartbreak, because that’s not how people typically interact.”

Kotler credits her early ADHD diagnosis with summoning a mission to help others who face arduous paths and learning to convert her own challenging characteristics into strengths.

“It’s really difficult to separate your personality, your identity, from your diagnosis. They are deeply connected,” Kotler said. “Most of the training I got through school was how to be successful there, which was important, but not sufficient when you are trying to survive the rest of the world. I needed support.”

She got that growing up in a family of feminists and activists. Outings with her parents often involved bringing snacks to teachers on a picket line, or sitting with striking daycare workers. Her early engagement in local activism, and her rejection of gender stereotyping, grew into a commitment to social justice.

“I never felt like I wasn’t smart because of ADHD; my parents did not emphasize my diagnosis, and my family talked to me about complicated issues,” she said. “They knew I was capable and also knew I needed to learn the skills to get things done.”

Kotler combined multiple therapies, including neurofeedback, focus training, and muscle-relaxation exercises, to manage her symptoms, but it was years before she could sit still in a classroom. As an undergraduate at McMaster University, studying psychology, neuroscience, and behavior, she often needed to Skype with her mother to do her work.

“It was hard for me to sit and do the work alone. I have some hyperactivity,” she said. “I just needed to know somebody was there helping me.”

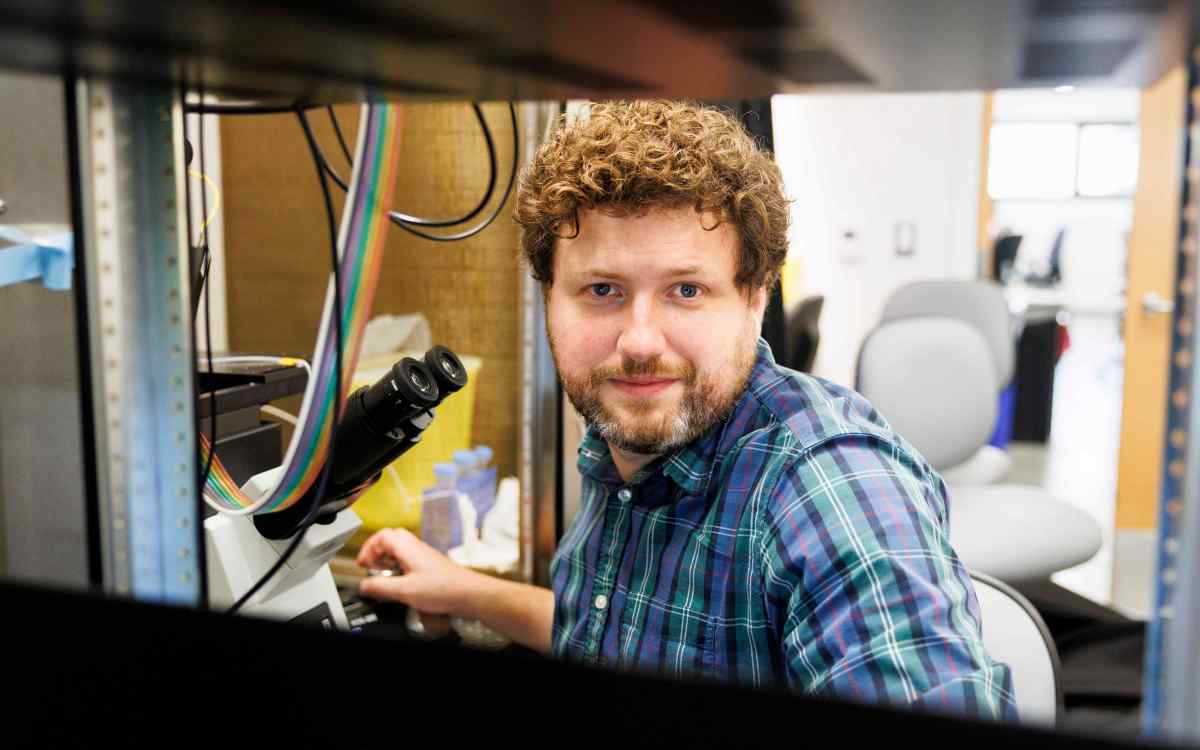

One of Kotler’s favorite strategies to combat ADHD is to ask a lot of questions, a habit that makes her a great conversationalist and a welcome participant in GSAS social events such as “Science by the Pint” during Wintersession 2014.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

After graduating, Kotler worked at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto as a research assistant in psychosocial oncology, palliative care, and bereavement, a field in which she retains an interest.

But it was the dynamic between genes and kinship — how genes evolve in interdependent relationships — that drew her to Harvard in 2012 to explore evolutionary medicine.

While her academic focus was on pregnancy, parent-offspring relationships, and sexual development, Kotler also turned her attention to sexual violence treatment advocacy. In 2015 she joined the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center (BARCC) as a volunteer hotline counselor. (She is now a peer supervisor.) Kotler said her struggles with ADHD have produced an ability to connect with women in difficult circumstances; she uses her scientific training to look at the biological drivers of sexual violence — including the role of evolutionary genetics.

“People are afraid of asking the biological questions about sexual violence because it’s so emotionally wrought,” Kotler said. “But putting it in the lens of a public health issue is more scientifically accurate and can form better education programs and better, broader policy.”

“Jenna provides a lot of support around very serious stuff, and she does it with such a positive, caring energy,” said BARCC senior hotline coordinator Jesse Moskowitz. “People feel so confident, calm, and prepared after spending time with her. It’s obvious she operates from the heart in everything.”

At Harvard, Kotler organized “Ladies Who Lab,” an OEB departmental group that addresses women’s issues, helps resolve conflicts, and shares pertinent research about women and their roles in science education and academia. She also works with the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Action Coalition, helping organize political advocacy and education programs, workshops, and campaigns.

“I’ve always been really interested and engaged in women’s rights and gender politics,” she said. “It can be scary, but I’m always optimistic about positive outcomes, which is why I’m good at talking about death and dying, cancer, and rape. If I can do something to help, I want to” — and that includes drawing on her own experience to encourage others.

“For a long time, I could not be left to my own devices, I needed somebody there helping me. I would be struggling trying to do the same thing for four days and I couldn’t do it. But it’s doable,” she said. “If people don’t talk about their diagnosis or coping skills, others won’t know it’s a realistic option. I’m at Harvard, going to be a Ph.D., it’s positive to talk about.”

Kotler has strategies to maintain what her family used to call the F-word: focus. There are the snuggles she receives from Juno, the support dog always by her side. She has copious notepads for writing down all the things she needs to remember; she schedules almost everything and checks her calendar frequently; and she uses Pomodoro, a timer-based application that breaks down tasks into 25-minute chunks.

One of her favorite strategies is to ask questions. Everybody has something to add, she said, and she can learn things she may not have known otherwise.

Self-acceptance? That she’s got down.

“I always liked who I am, being quirky and unique. I’m not ever going to be perfect,” Kotler said. “But now I’m not afraid to say yeah, I’ve worked really hard, I’m capable, successful, and this is how I got here.”