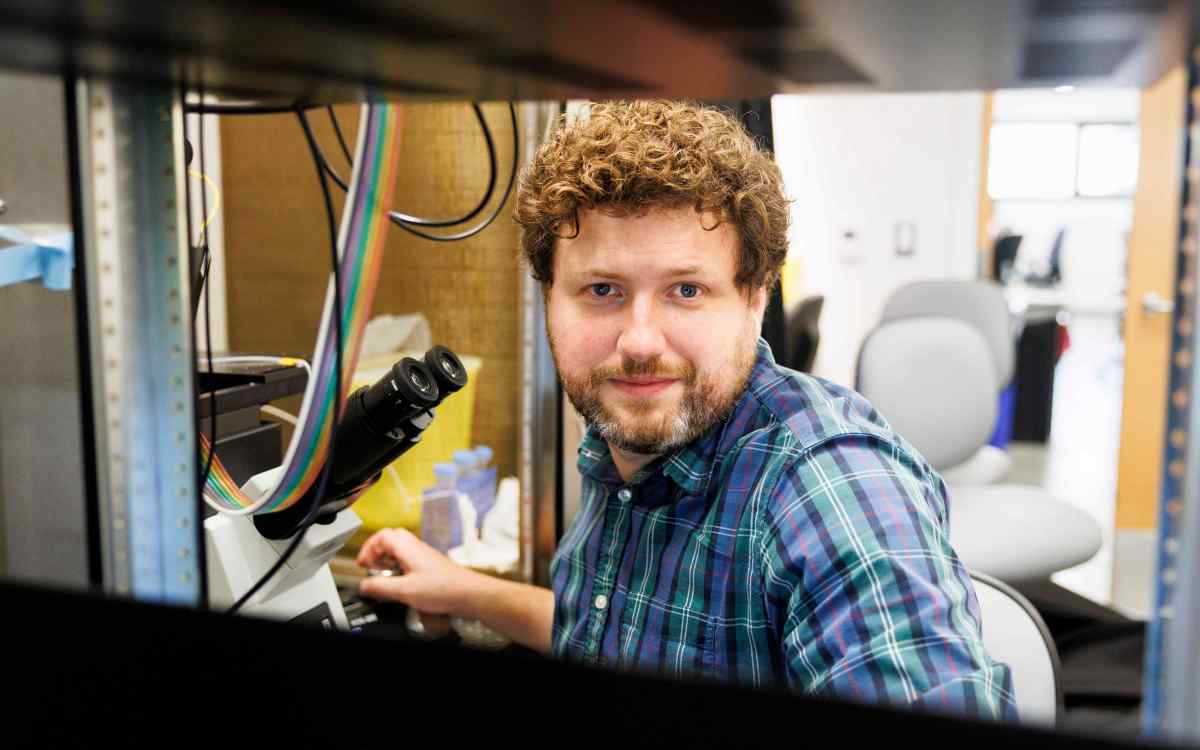

A multimaterial bioprinting of vascularized, stem cell-laden thick tissues used in kidney tissue research by Kim Homan and David Kolesky of Professor Jennifer Lewis’s laboratory at Harvard University.

Lori K. Sanders/Harvard University

Seeding startups

Office of Technology Development welcomes entrepreneurs-in-residence to Harvard research labs

One Harvard research team has shown how an immense amount of data can be stored in custom-built strands of DNA. Where does that technology’s greatest value lie? Another lab has a 3-D printer knitting cells into blocks of living tissue with embedded, functional vasculature. Should these be deployed as models of disease, for drug discovery, or as the future of wound healing?

Each case requires an experienced leader’s systematic approach to turn a stunning innovation into a transformative business plan.

For advanced technologies across the University, a new entrepreneur-in-residence (EIR) program launched by Harvard Office of Technology Development (OTD) might offer a crucial bridge to commercial development.

“We want to see as many startups come from Harvard as possible,” said Isaac T. Kohlberg, senior associate provost and chief technology development officer. “In order to launch startups, you need initial CEOs and executives, and you need to identify them early on to work with the researchers and scientists.”

The first EIRs in the program, in 2017, included Shahid Azim, a serial entrepreneur who focuses on bioelectronics and non-invasive sensing, and Nat Harrison, a Chicago-based entrepreneur with a background in materials science, chemistry, and optoelectronics. Their time on campus sparked discussions beyond their expectations and nurtured business development efforts that still continue.

With at least two more EIRs on board for 2018, and further recruitment underway, OTD’s program is poised to deliver a new set of perspectives — and perhaps a sense of urgency — to faculty, postdocs, and graduate students who feel a tug toward the startup life.

“Even for the kind of businesses that come out of universities, the proprietary tech is only one piece of it,” said Harrison, who relocated to Boston to participate. “There’s always more value that’s built in either the business system or the enterprise that’s launched.

“I often see a tendency among researchers to say, ‘Let’s wait, let’s get our ducks in a row and do another paper. Let’s not tell people about our technology yet.’ There’s kind of a stealth bias, and I think that’s the wrong bias,” Harrison said. “I think you need to have a speed bias. The speed bias says, talk to more people and figure out if there’s a ‘there’ there — if they want it, if you can do it.”

Bridging lab to business

While related programs exist at Harvard Business School, Harvard Innovation Labs, and Harvard’s Wyss Institute, bringing EIRs into the Cambridge and Longwood labs for extended periods represents a new mechanism for focused technology development efforts at the University.

“Commercially speaking, when you talk about transferring research from the academic to the real world, the transfer is rarely successful without having talented, dedicated individuals to play a major role in that trajectory,” said Kohlberg.

Bruce Bean, the Robert Winthrop Professor of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School (HMS), knows the difference an entrepreneurial adviser can make. His lab co-developed a technology that could one day treat chronic cough and other ailments, and a startup is in the works.

“As scientists, we can take the work up to a certain point, but most of us have little or no experience in what it takes to go from promising effects in animals to [human] clinical studies, and particularly to know what investors are going to look for and what their concerns are,” Bean said. “A seasoned entrepreneur has the expertise to go from the science to figuring out whether it’s going to be commercially viable.”

Since 2005, when Kohlberg arrived at Harvard to lead OTD, this unit of the provost’s office has helped to launch more than 100 companies built around Harvard technologies. The staff is focused on providing a series of bridges from the lab to the startup, whether in the form of research funding, advice and networking, or strategic planning.

Much of OTD’s success has come from the life sciences, where commercially promising research can get an extra boost from the Blavatnik Biomedical Accelerator, and where emerging companies benefit from Boston’s robust early-stage venture ecosystem. Heavy hitters have included Genocea Biosciences (vaccines), Selecta Biosciences (biologic therapies), Editas Medicine (genome editing), Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals (antibiotics), and Magenta Therapeutics (stem cell transplantation). Outside of the life sciences, Harvard’s pilot Physical Sciences & Engineering Accelerator has demonstrated early success with startups like Voxel8 (3-D printing), Perusall (educational technology), and RightHand Robotics (warehouse automation).

“Harvard is producing a lot of high-quality stuff that’s got commercial legs,” said Harrison, who spent much of his time on campus last year connecting with researchers at the intersection of materials science, computer science, and biology. “The smaller departments are punching above their weight.”

Essential input

The EIR program promises to provide greater entrepreneurial and strategic leadership to translational research projects University-wide. Kohlberg plans to bring in between five and eight EIRs with expertise to inform all areas of life science and physical science and, over time, rotate in new candidates. The point, he said, is that in the right hands — with companies that are committed and well equipped — potent innovations can be developed to their fullest potential.

To maximize the potential for serendipity, the program is flexible. According to Kohlberg, an EIR can work horizontally across a number of projects, groups, and individuals, scanning the fertile research environment for opportunities. Or, an EIR can engage vertically, identifying a specific project and working with the research group to turn the concept into a startup.

In either case, EIRs can make connections to prospective investors and provide advice, mentorship, and coaching about the startup process. They can offer counsel on business models and on fundraising strategies, as well as on how to pitch an idea and address the business challenges unique to each innovation.

“The EIRs will talk to all these various faculty, postdocs, and graduate students. We’ll introduce them to people, and they’ll find a bunch on their own,” said Sam Liss, executive director for strategic partnerships in OTD. “Being an EIR gives them a platform from which to go find interesting technology and see what develops out of it.”

For Azim, who previously helped launch three venture-backed startups, inspiration came easily: “I was just blown away by people’s curiosity to solve problems, and their creativity, frankly.” He said it was rewarding to be able to contribute an external perspective. “As they are deep into very specialized research, most of these students and researchers don’t have the professional network at this stage to tap into industry thought leadership or key decision-makers. The EIR program is a really good mechanism to bridge that chasm.”

Harrison and Azim each have met and mentored many research teams at the University.

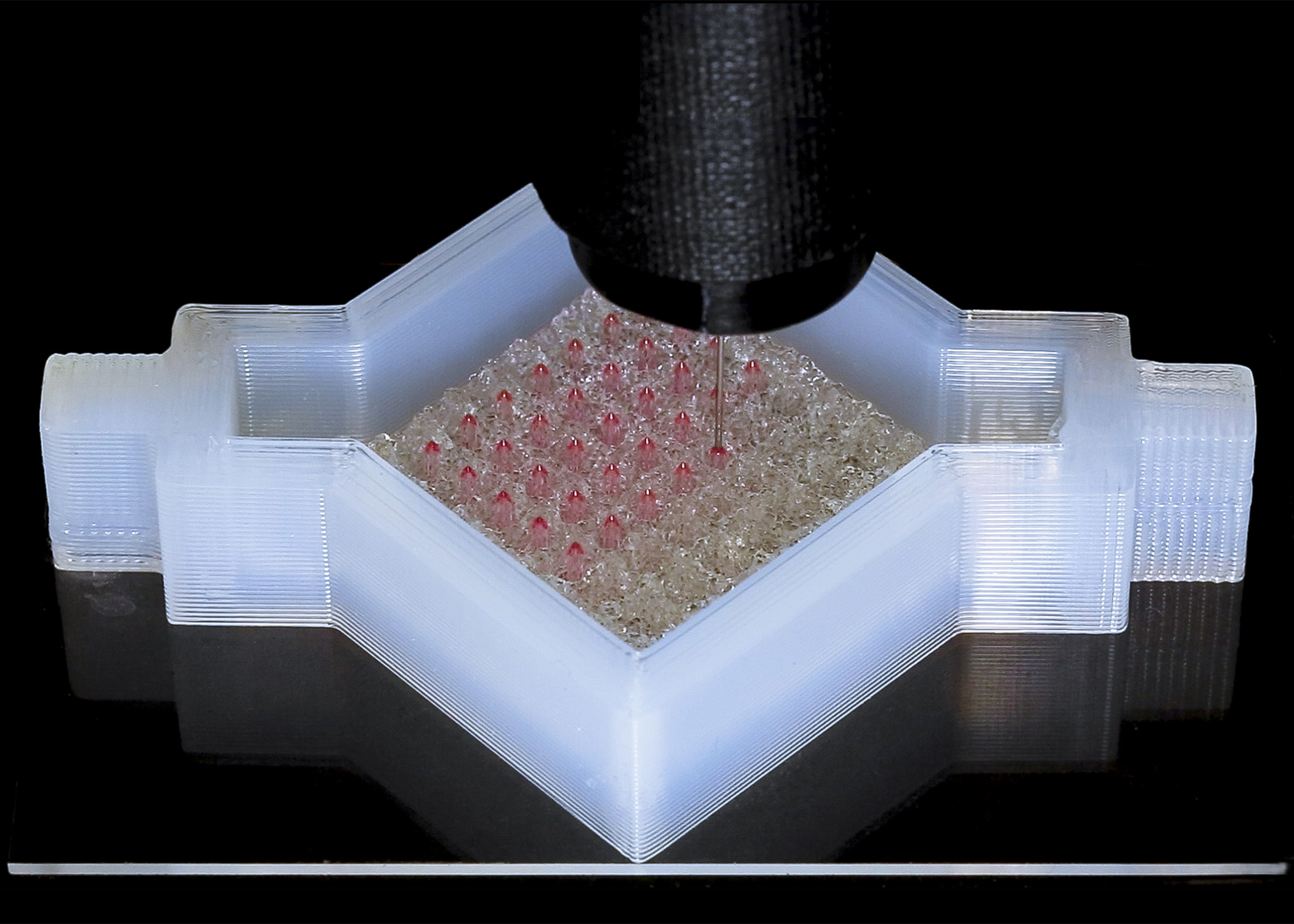

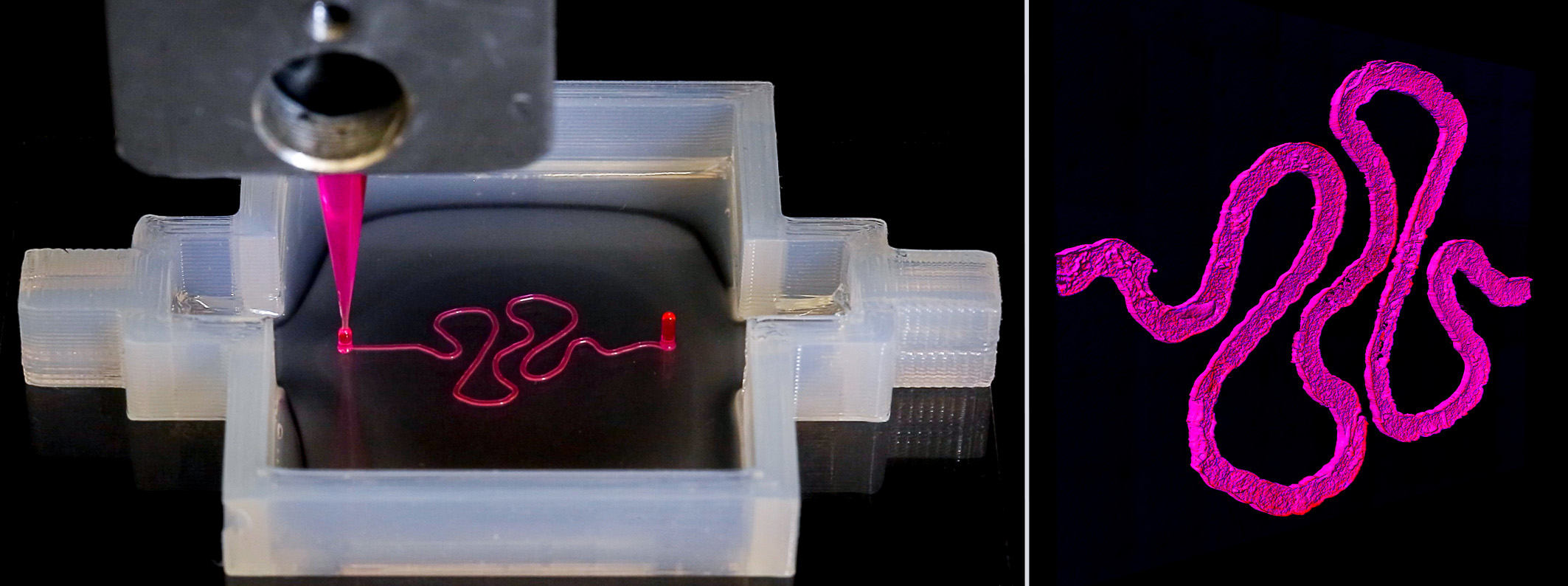

Left: Bioprinting in the Lewis lab creates a 3-D structure that mimics the architecture of a kidney — specifically a convoluted proximal tubule surrounded by an extracellular matrix. Right: Fluorescent image of confluent epithelium within the printed proximal tubule.

Images courtesy of the Lewis Group/Harvard University

Azim said it was like being “a kid in a candy store.”

“A lot of these building blocks in the lab, very early-stage, are really pushing the boundaries,” he said. “You start to see a pattern emerge where eventually dots converge from various pieces that would eventually deliver a really, really large impact, whether it’s in healthcare, transportation, or any number of industries.”

“I was privy to see some data that was still in the lab, especially from the Lewis Group,” the lab where living tissues are printed from bio-inks, “and it was just amazing to see what is even possible. It’s easy to see where this work can have a huge impact.”

That experience, of both intellectual stimulation and practical contribution, is now open to Gus Simiao, who joined the EIR program in January. Simiao is a principal at venture investment group CEVG. He specializes in startups in the areas of sensors, robotics, machine learning, energy, and mobility.

Raffaella Squilloni, M.B.A. ’10, is also newly on board, with a plan to focus mainly on the commercial development of a new vaccine platform. As an HBS Blavatnik fellow last year, Squilloni connected with researchers at HMS who are advancing a live attenuated vaccine for Zika, Dengue, and West Nile Virus, as well as a novel self-adjuvanting mRNA vaccine platform that can be applied to some infectious diseases or even cancer. As an EIR, she will work with the research team to define a business plan.

The vaccine project has entered the “final stage of incubation in which both the technology and the business proposition are readied for the launch of a new company,” said Michal Preminger, executive director of OTD’s HMS office. Squilloni is poised to take the leadership role in the startup, Arbothera, when her time as EIR concludes, as “someone who will live and breathe and focus 100 percent of her energy on getting this company off the ground.”

Finding the right fit

Many of OTD’s directors of business development launched companies of their own in earlier careers, yet the level of focus and expertise the EIRs can bring complements that experience and “expands the ways we can be helpful,” Liss said. “It facilitates researchers’ access to someone who has good access to the capital markets, can raise money, and has demonstrable experience taking an early-stage technology and translating that into a real startup. It’s a unique role.”

The ideal EIR, he said, can prompt an “intellectually honest discussion about whether the technology is really appropriate to be the platform for launching a startup or not.” Does it truly solve a problem? What might the product be? How is that validated? What is the big picture?

OTD’s program opens a potent opportunity for talented entrepreneurs “to work with some of our most visionary faculty at the earliest stages of startup formation,” Kohlberg said. It offers an invitation to browse, to forge new connections — and perhaps to catch lightning in a bottle.

“These university spinouts very often work best where there’s someone in the research group, a postdoc or a Ph.D., who comes with the business when they’ve finished their work or their education on campus,” said Harrison. “The success scenario is a match between an entrepreneur and a researcher.” That success, he added, depends on being in the right place at the right time.

“The opportunities are there, and the doors are not that hard to open for those who are interested,” Harrison added. “Normally you would expect that you’re looking for the needle in the haystack. Here, I would say there are plenty of needles.”

Are you interested in becoming an entrepreneur-in-residence? Please contact OTD.