Harvard researchers have traced the geographic sources of methylmercury in seafood, with 47 percent of Americans’ exposure coming from tuna and shrimp.

Credit: iStock

Study tracks mercury sources in seafood

Harvard researchers map geographic areas of most concern in reducing neurotoxin

Order a sushi platter in the U.S. and your plate will likely include tuna from the South Pacific, crab from the North Atlantic, and farm-raised shrimp from Asia.

Researchers have long known that exposure to the neurotoxin methylmercury (MeHg) comes almost exclusively from eating seafood. But the geographic origins of that exposure haven’t been well understood.

Now, researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have traced the worldwide origins of methylmercury in the U.S. diet and examined changes in those sources in recent decades, as ecosystems and palates evolved. Understanding the sources of methylmercury exposure in the diet is important in developing strategies to reduce mercury emissions.

“Seafood is one of the last wild foods consumed by humans and an essential source of protein and micronutrients for many populations,” said Elsie Sunderland, the Thomas D. Cabot Associate Professor of Environmental Science and Engineering and senior author of the study. “This work shows that global environmental quality and the health of the oceans affects the food we eat.”

The research is published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives.

Graphic by Leah Burrows/SEAS

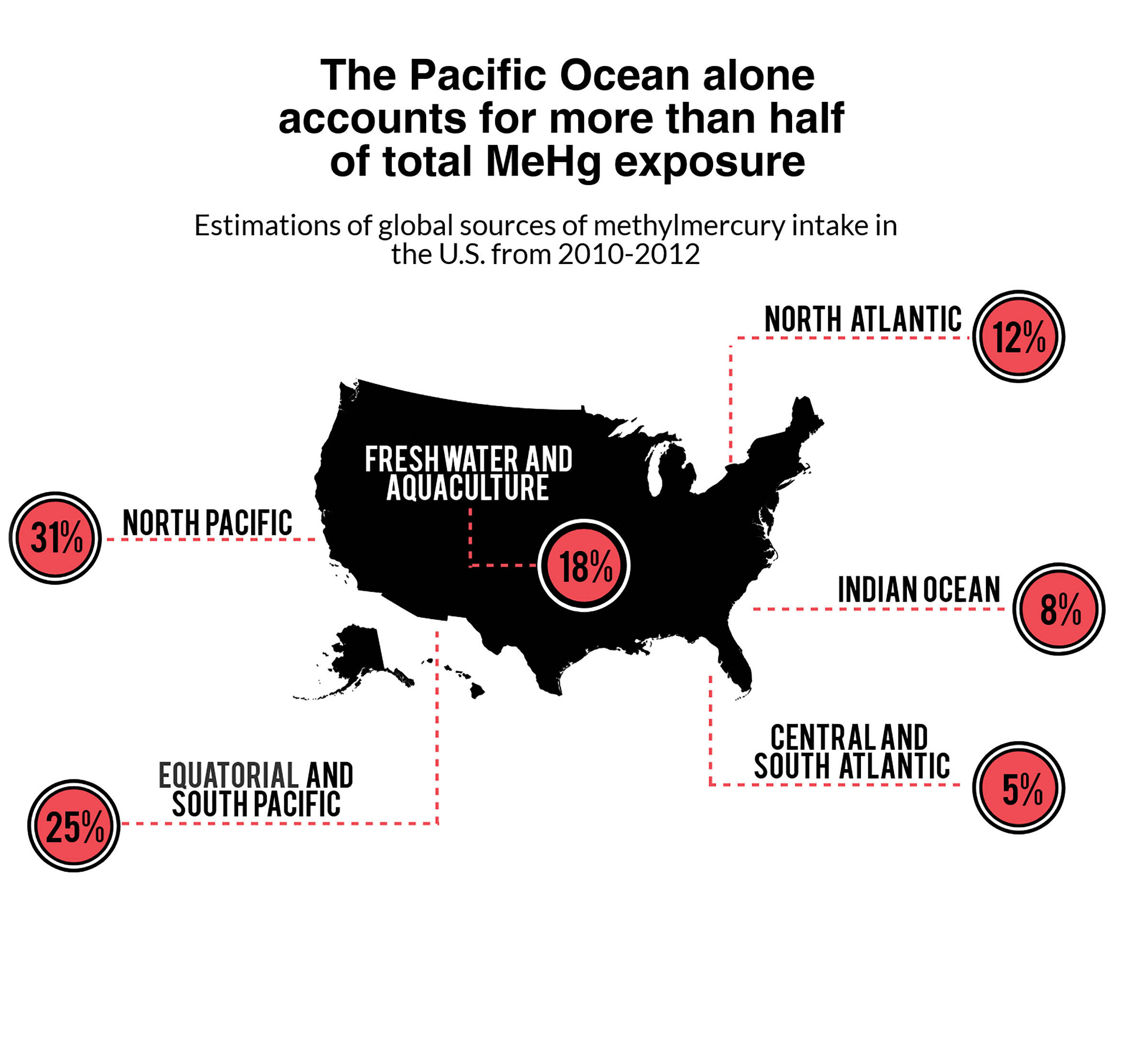

The researchers found that open-ocean fisheries account for more than half of all U.S. methylmercury exposure. The Pacific Ocean is the largest source of such exposure, as mercury emissions globally have shifted from North America and Europe to Southeast Asia and India. The Equatorial and South Pacific waters are the primary regions for tuna — which contribute the largest fraction of U.S. methylmercury intake.

Graphic by Leah Burrows/SEAS

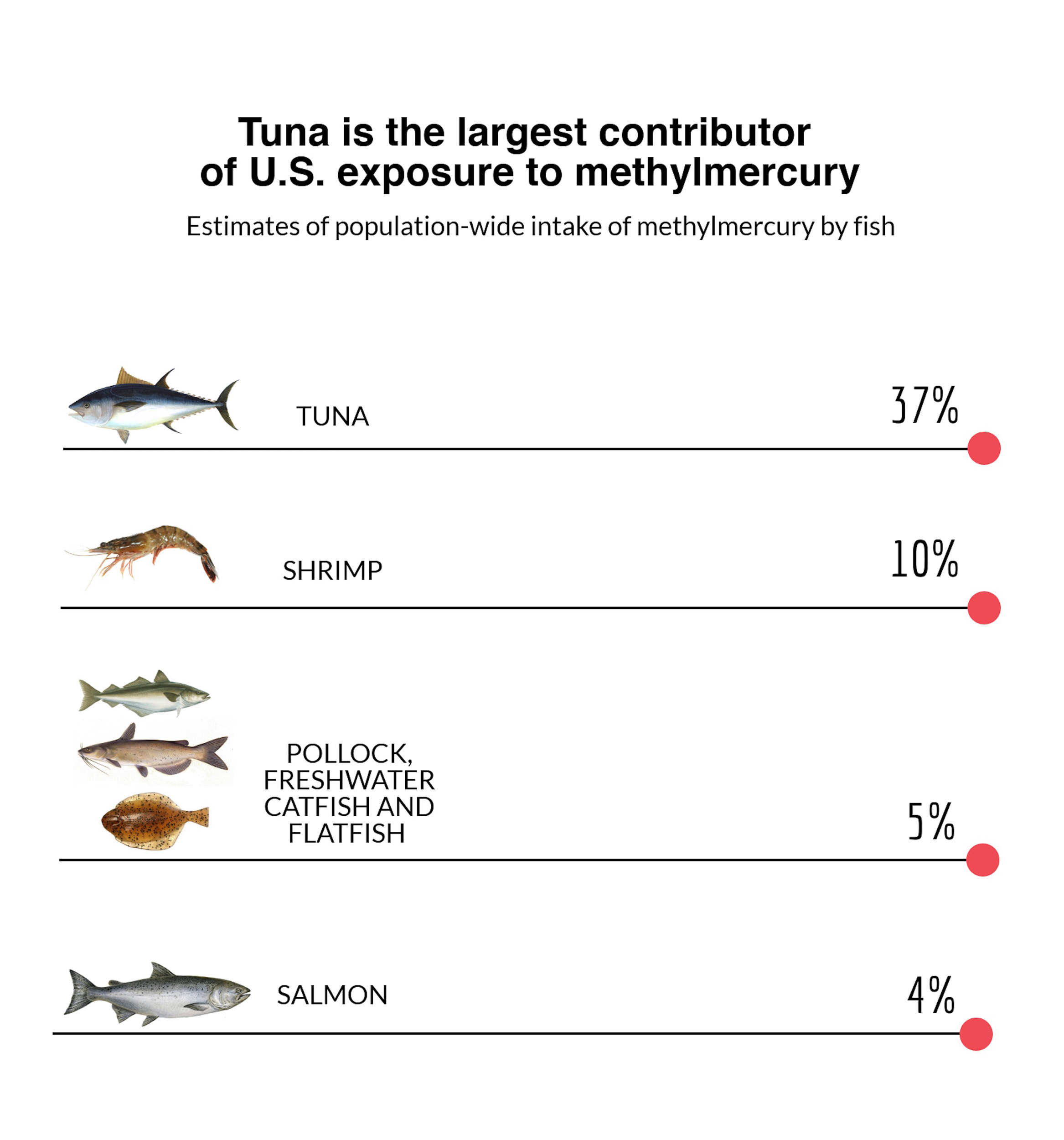

Between 2010 and 2012, shrimp was the most-consumed seafood in the U.S. Added together, shrimp and tuna accounted for almost four out of every 10 seafood meals.

Because tuna has relatively higher concentrations of methylmercury, fluctuations in its consumption have a huge impact on U.S. exposure. Between 2000 and 2002, canned tuna was the most-consumed seafood in this country. While overall consumption of tuna is down compared with previous decades — in large part due to a save-the-dolphins campaign — methylmercury exposure is up because more people are consuming it in the form of sushi.

But food choices aren’t the only factor governing methylmercury exposure. Climate change is affecting how people harvest and consume seafood.

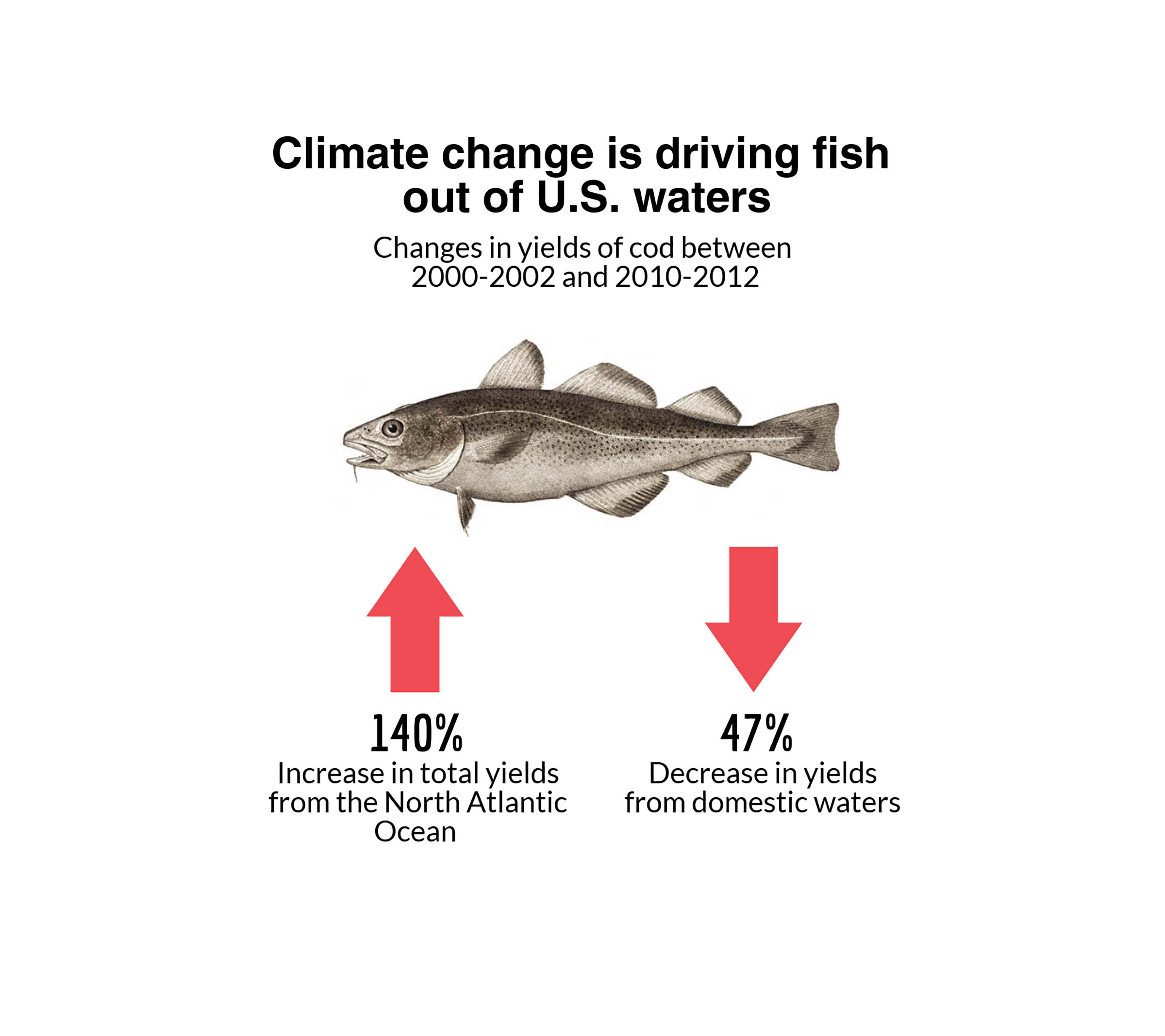

“This study shows that decadal climatic variability and global warming have strong impacts on the U.S. seafood supply,” said Miling Li, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and co-author of the paper. “Climate change significantly alters the sources and burdens of human mercury exposure.”

Increasingly, fish species, including the popular cod, are swimming out of reach of U.S. domestic fishing vehicles toward cooler waters in the North Atlantic.

Graphic by Leah Burrows/SEAS

The researchers hope that the Minamata Convention, an international treaty to reduce mercury emissions that was signed in 2013 and enacted last year, will mark the beginning of global efforts to reduce mercury in the environment.

“This research is especially pertinent in light of the Minamata Convention,” said Kurt Bullard ’17, co-author of the study. “We hope this study will help prioritize strategies to reduce environmental MeHg concentrations here in the U.S. But any global efforts to reduce MeHg concentrations would beneficial for U.S. consumers.”

The paper was supported in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.