The objects of their reflection

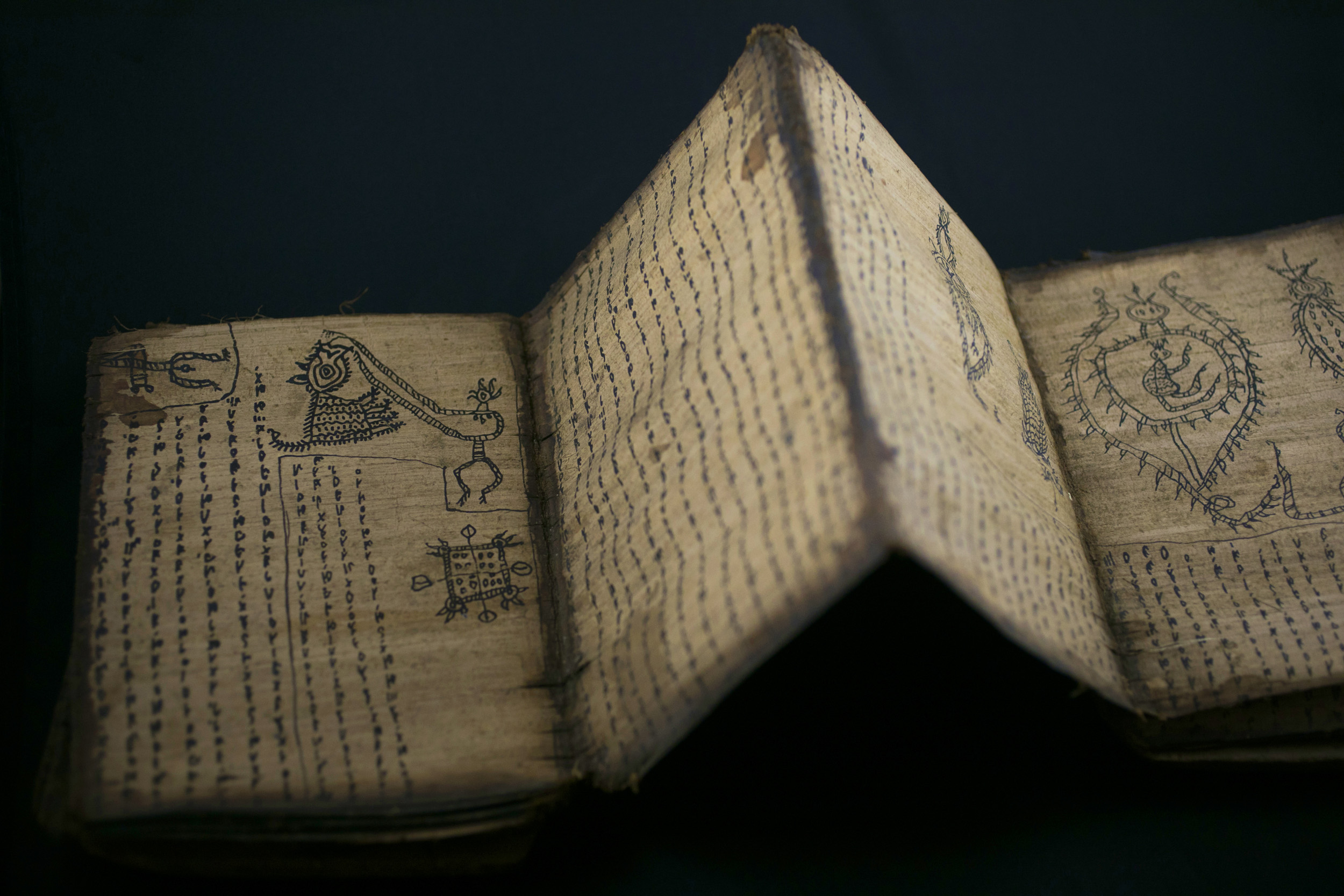

This Batak accordion book of spells was used in rituals, spellcasting and healing, according to librarian Emilie Hardman. It was often worn draped across the body of the practitioner, she said.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Whether a spell book or Edison bulb, Houghton’s treasures charm students and illuminate research

It’s hard to imagine even the most jaded student entering the Houghton Library without a sense of awe. Within these walls, you can read a letter signed personally by Vladimir Lenin, unfold a book of spells from Indonesia, and marvel at Emily Dickinson’s writing desk and chair.

As Houghton celebrates its 75th anniversary, scholars take a look back at how some of the library’s rare holdings have inspired their research. Their stories are paired with audio clips from Houghton librarian Emilie Hardman, who provides some context for the the objects.

* * *

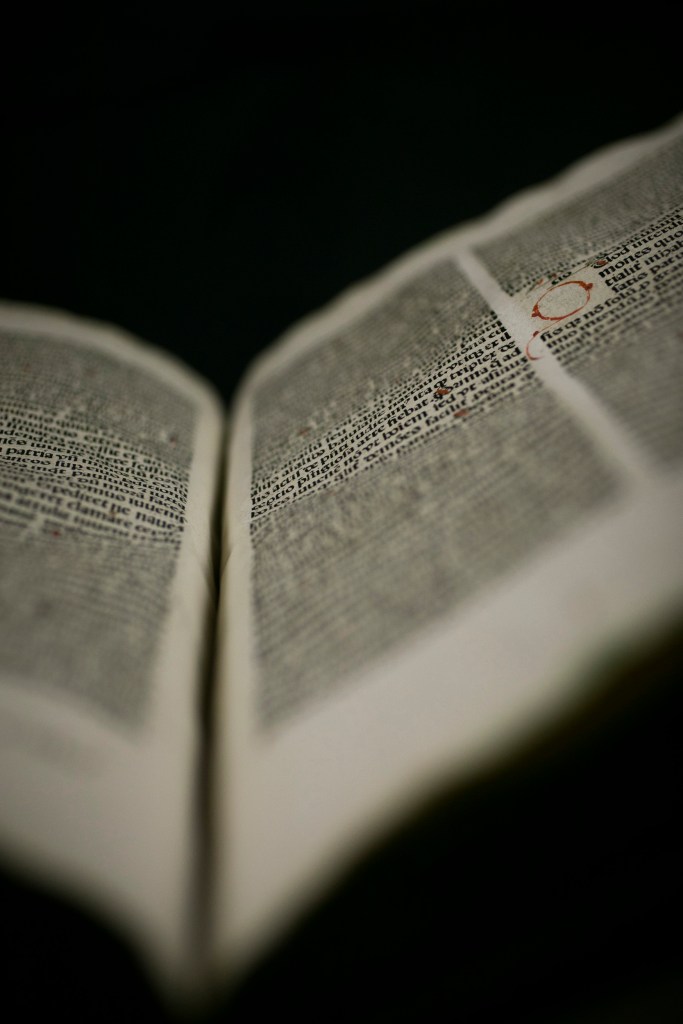

Katherine Leach, a Ph.D. student in Celtic languages and literatures, took her students to Houghton to explore medieval and early modern tracts against witchcraft.

Librarian Emilie Hardman showed them original sources from the period such as the Malleus Maleficarum but to the delight of the class, she also rolled out an Indonesian spell book, bamboo sticks engraved with spells, and an Armenian charm scroll.

“The class changed because of what Emilie brought in to show my students,” Leach says. “There were two Armenian students in the class. Seeing that scroll blew their minds. They were posting on Instagram and texting other Armenian students.”

Leach says that as a medievalist, she’s often focused exclusively on texts and manuscripts but “seeing these artifacts made the topic more relatable, more real” for her students.

“I was so impressed with the collection and with Emilie,” Leach says.

‘Malleus Maleficarum’

Armenian charm scroll

“There were two Armenian students in the class. Seeing that scroll blew their minds. They were posting on Instagram and texting other Armenian students.”

Katherine Leach

Spell-engraved bamboo stick

* * *

Today, we can zoom in on any part of the world through Google Maps and Street View.

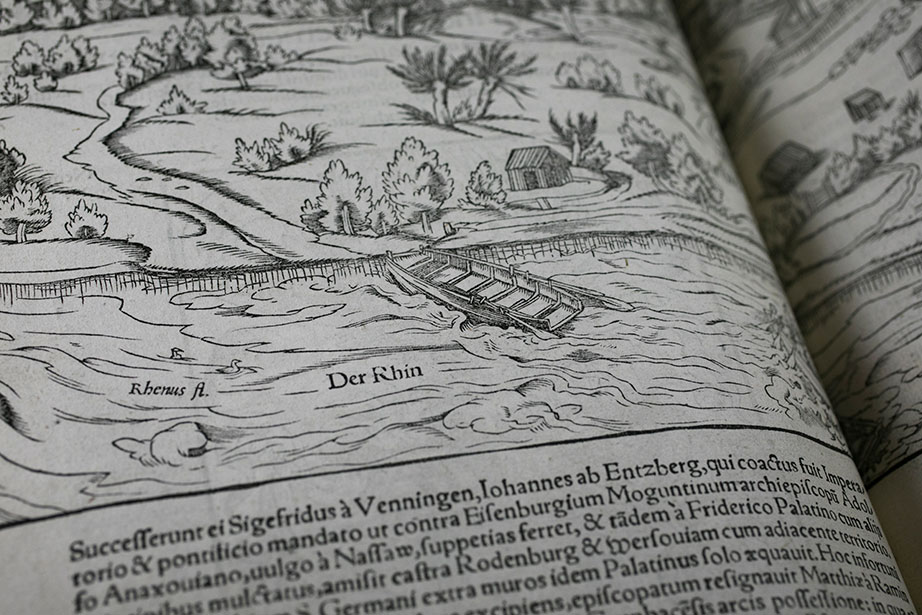

When German cosmographer Sebastian Münster made his Cosmographia, a book intended to capture the world as he knew it in the 16th century, he did not have the benefit of Google’s tools.

Instead, Münster recruited a resident from every German burg to provide him with drawings of their cities, says Jasper van Putten ’15.

A Ph.D. student in the history of art and architecture when he found the text at Houghton, van Putten launched a research project that would have astonished Münster.

Using GIS mapping tools — with landmarks such as church spires and old city walls as his guide — he overlaid the antique drawings from Münster’s book over modern satellite maps of German cities.

Surprisingly, the old illustrations were fairly accurate, van Putten says. However, in some, important landmarks were nudged into positions that made the cities look more important.

“One city moved a castle about 300 meters to put it in the center of the view,” according to van Putten.

The Cosmographia stayed in print for about 90 years with maps added or redesigned in later editions, van Putten says, so he stacked up the views in GIS to flip back and forth and see how the cities had changed over time. He has put his work online, giving researchers and history buffs anywhere a bird’s eye view of the way that 16th century Germans saw their world.

Cosmographia

* * *

Jeremy Zallen ’14 wanted to write about the history of illumination for his Ph.D. dissertation. While exploring the earliest forms of electric light in the United States he came across the records of the Bijou Theatre.

In the 1880s, the Boston venue became the first fully electrified theater in the country. A single, fragile light bulb survived from that era and sits in Houghton alongside the theater’s financial records.

If you put this tiny bulb on a shelf in Home Depot, you might not notice that it is a relic from the 1880s, with a bamboo, rather than tungsten, filament.

“The bulb would have been made in Menlo Park, under the direction of Thomas Edison. In those days, they were experimenting with a number of filament types,” Zallen says. “The bamboo filament would have been less bright than previous electric light bulbs, but it would have lasted at least a few days — which was a big improvement.”

The bulb brought up more questions than answers for Zallen: Why did someone save this solitary light bulb? Were the electric lights’ primary purpose functional, or were they really just props to publicize Edison’s invention?

Light bulb from the 1880s

* * *

Andrea Bohlman, Ph.D. ’12 in music, unexpectedly discovered a series of underground recordings at Houghton while preparing for a trip to Poland that she says, “changed my research methodology forever.”

“I was probably on page 57 of search results in the HOLLIS catalog when I stumbled upon the Solidarity Collection,” Bohlman said.

Comprising dozens of cassette tapes belonging to Poles who resisted or subverted the Communist government as a part of the Solidarity movement of the 1980s, the collection opened up a whole new world of research for Bohlman.

“Now everywhere I go to conduct research, I look for weird sound recordings.”

Andrea Bohlman

Bohlman heard everything from politically conscious Polish rock music to bootlegged news reports from broadcasters sympathetic to the Solidarity movement.

“Cassette tapes are convenient materials for politically subversive communication — you can wipe them with a magnet, you can record over them, but you can also copy them infinitely,” Bohlman said.

Solidarity-related cassette tapes became the cornerstone of Bohlman’s dissertation, now a forthcoming book, “Musical Solidarities: Political Action and Music in Late Twentieth-Century Poland.”

“Now everywhere I go to conduct research, I look for weird sound recordings,” Bohlman says. “They’re an untapped resource.”

To read the full story, visit the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences website.