Workers with strong social skills are increasingly valuable to employers, according to a new paper by Professor David Deming, while opportunities are shrinking for STEM specialists.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Golden age for team players

Strong social skills increasingly valuable to employers, study finds

Employers increasingly reward workers who have both social and technical skills, rather than technical skills alone, according to a new analysis by a Harvard education economist.

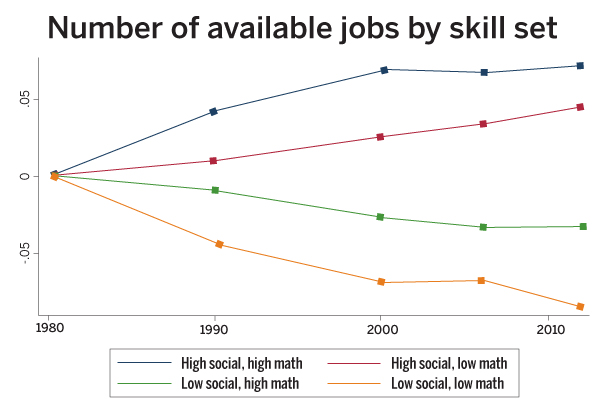

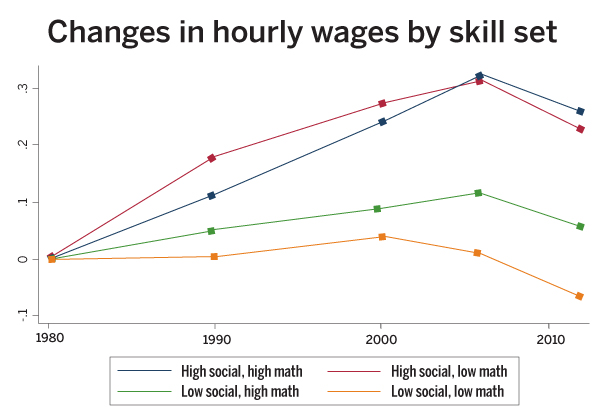

Research by David Deming, a professor of education and economics at the Graduate School of Education and a professor of education and public policy at the Kennedy School, shows that workers who combine social and technical skills fare best in the modern economy, as measured by a 7.2 percentage point increase in available jobs and a 26 percent wage increase between 1980 and 2012.

Those in technical jobs that have few requirements for social skills, such as specialists in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields, actually saw the number of jobs decline 3.3 percentage points. While wages for those jobs rose over the study period, the increase was roughly a quarter of that seen in jobs requiring both technical and social skills.

Automation and computerization, which first affected repetitive, low-skilled industrial work, are penetrating fields that, though perhaps more cognitively demanding, also have elements that are routine and somewhat repetitive, Deming said.

“Jobs where you just sit in a cubicle or on the factory floor and work in isolation are going to disappear,” he said. “In the long run of history, jobs that get replaced are drudgery. In the long run, we will be better off.”

The study’s good news, Deming said, is that people can still thrive in an area where computers come up woefully short: interacting with other people. Specifically, today’s job market favors those who have the skills to be good team players.

“Social skills reduce the cost of coordinating with others,” Deming said. “Each time there’s a new set of people, they have to figure out anew what their roles are.”

Deming’s paper, to be published next month in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, lists nursing, teaching, therapy, medicine, and law — all fields that require significant interpersonal interaction — among the occupations growing fastest as a share of the labor market. Engineering and architecture are among the occupations whose workplace share has shrunk.

The results partly reflect how the nature of certain fields is changing, Deming noted. Engineers and computer programmers are still needed, but positions in which they might do the bulk of their work alone in a cubicle are giving way to more team-based, project-based approaches, Deming said.

“I don’t think STEM jobs are going to disappear,” he said. “Technological change is disrupting the nature of existing jobs.”

The study grew out of Deming’s sense that employers’ desire for strong social skills in new hires was being ignored. For years, employer surveys have listed the ability to communicate well and work as part of a team among important skills for new hires. Nonetheless, economists and educators have continued to emphasize hard skills.

“We don’t have a way of measuring how some people work on teams,” Deming said. “We don’t have a formal way of thinking about that.”

Deming took a step toward a providing one by developing a mathematical model in which group members trade tasks among themselves to optimize use of their particular skills, which in turn makes the group more efficient. He then applied the model to national employment data sets, which allowed him to quantify the dependence of particular jobs on social skills and see how those jobs changed over time.

The results, according to his paper, reinforce prior research showing that skilled jobs are becoming less routine, perhaps because machines are taking over routine work.

The findings have implications for U.S. schools, Deming said. To the extent that teachers prepare students for the job market, the study indicates that team-based project work should be a point of emphasis.

“If you want schools to train people for the workplace, you have to simulate the situation they encounter in the workplace,” he said.