From the islands to the bayous

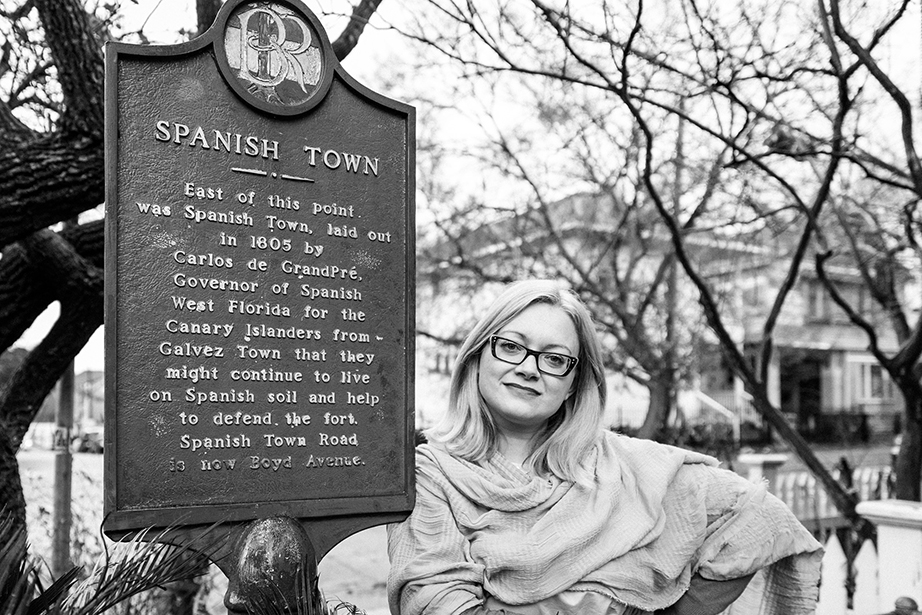

Grad student chronicles fading culture of Canary Islanders in the U.S.

It was 1997 in the Canary Islands and Thenesoya V. Martín De la Nuez, then 18, was struck by the voice of a Louisiana man singing a Creole version of a Spanish poem.

“I was so moved, I cried. Here was an American, a U.S. citizen — and he was speaking like us, like Canary Islanders,” Martín says.

The emotional connection sent her on a mission to chronicle the fading culture of the descendants of Canary Islanders who settled in Spanish Louisiana in the 18th century.

Her research gained urgency in 2005 when news reports of Canarians rocked by the destruction of Hurricane Katrina compelled her to reach out to members of the diaspora community and meet them face-to-face.

Now a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) and a teaching fellow in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Martín’s research has bloomed into a sprawling cultural documentary project, traveling photo exhibit, and book.

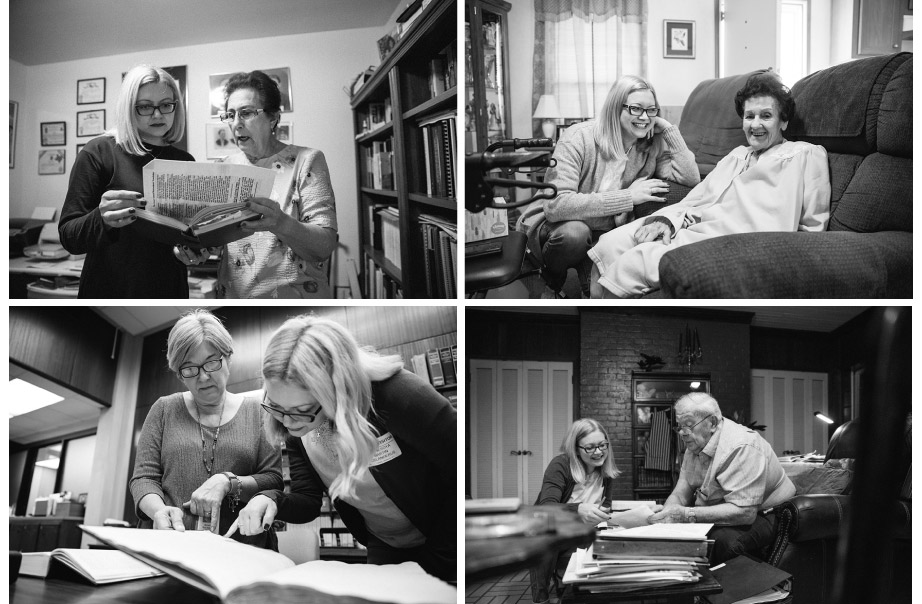

The book will incorporate more than 100 interviews and 8,000 photographs collected during four years of fieldwork with her husband, photojournalist Aníbal Martel, which help make up the Cislanderus project. The name is a sort of acronym of Canary Islanders and U.S. that also intends “us” to emphasize the commonalities.

Martín said the book “will be a story of cultural survival, investigating how the complex Canarian cultural legacy has survived or, in most cases, been reinvented in a complicated process of cultural nostalgia.”

“I had been reading for years, but I was always missing something,” she said. “The faces of people. Where are they? Who are they? Do they seem like Canary Islanders right now?

“I didn’t have any idea of how they looked, how they dressed, where they lived or what they did. I wanted to be there. I wanted to understand how their cultural legacy developed over three centuries. I wanted to understand how successive waves of immigration and migration from the Spanish peninsula and the Caribbean, as well as marriages into the Cajun community, shaped and affected that legacy.”

The couple began their investigations in Delacroix Island, Shell Beach, and Reggio, unincorporated communities in St. Bernard Parish, New Orleans, then followed a complicated map of Canary Island descendants scattered throughout Louisiana, including around Baton Rouge and the lower Mississippi River. Today they have expanded their fieldwork to San Antonio, Texas.

“We want to document the present,” Martín said. “It’s the book I looked for at the beginning, but it didn’t exist. So I am writing it.”